Using Maps for Genealogy Research, Part 3: Place of Origin and Immigration Stories

Genealogists seek records that describe names, places, and dates. Maps describe places and their names at a given point in time and, sometimes, even record the names of people. Unsurprisingly, then, maps are very useful tools for genealogists.

The New York Public Library Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division is home to 433,000 sheet maps, and 20,000 books and atlases published between the 16th and 21st centuries. The collections range in scale from global to local, and support the learning and research needs of a wide variety of users. This post, Place of Origin and Immigration Stories, is the third of a five-part series that describes some of the ways maps can be used for genealogical research.

- Finding records

- Fire insurance maps: exploring place and time

- Place of origin and immigration stories

- Topographical maps, and county maps and atlases

- Gazetteers and finding maps at The New York Public Library

Here, we look at maps that record our ancestors' place of origin, and that chart immigration to the United States. We'll also look at how maps might be used to illustrate an immigration story.

Place of Origin

The Library’s map collection is international in scope. Searching the collections, researchers will find maps that show where their ancestors originally came from. These maps represent the places of origin for some of the major groups of peoples to come to this country. Many people researching their family history are ultimately hoping to make a connection to a place of origin. How easy this is often depends on the records available. Were births, marriages, and deaths recorded? Were there censuses? If so, did those records survive? Maps are a powerful tool when it comes to learning about place of origin.

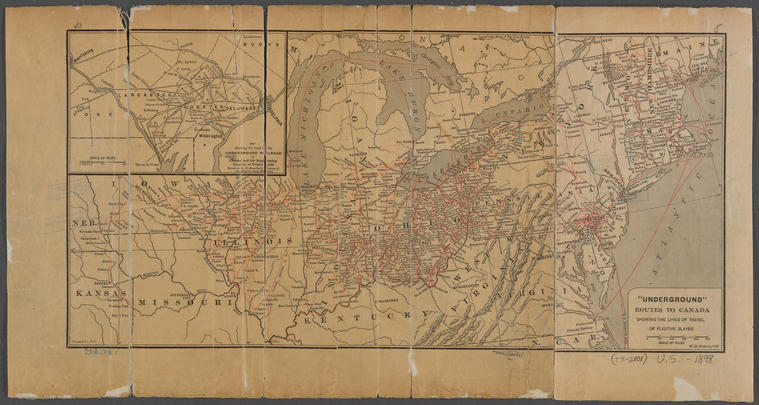

For instance, of the 900,000 people who arrived in the United States by 1790, 360,000 were forced immigrants from Africa. Most slaves came from countries in West Africa, from modern-day Senegal and The Gambia. This 1734 map of West Africa during the slave trade shows the principal towns and ports and is an important link to the place of origin for so many Americans.

Up until the 1880s, the largest groups of immigrants to the United States came from Germany, Ireland, and Great Britain, though significant numbers came from Scandinavian, and other Northern and Western European countries. Those places are represented in historical maps in NYPL collections.

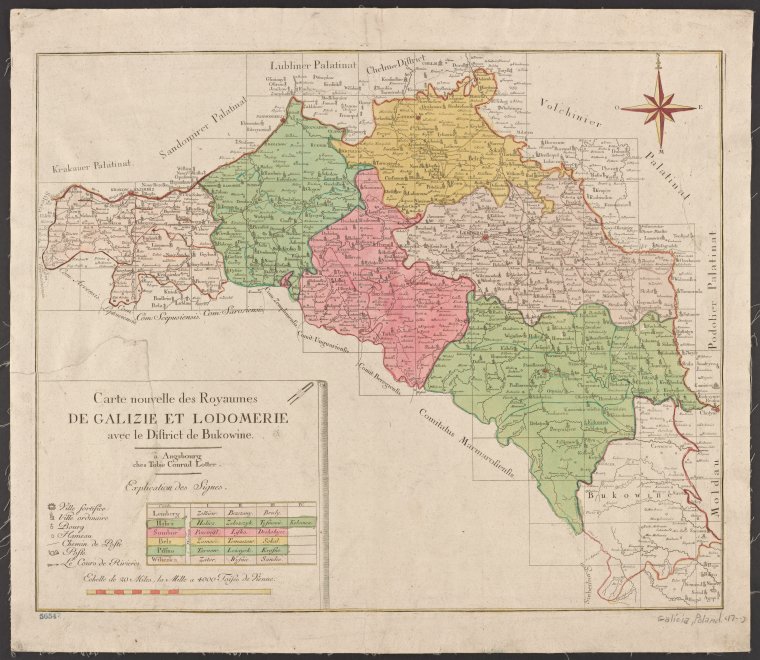

From the 1880s to the 1920s, most migrants came from Southern and Eastern Europe, Southern Italy, Poland, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Many Russian Jews immigrating to the United States came from Galicia, described here on a map from 1701, a region that straddled modern-day Poland and Ukraine. Galicia, like the Pale of Settlement, is a region not usually described on modern maps.

A Civil War veteran, Bernard Trainor (1816-1868) lived in New York City, where he enlisted in the 69th Infantry regiment, NY, perhaps better known as the Fighting Irish. An abstract from the 69th muster roll records his place of birth as Strabane, Co. Tyrone, Ireland.

In Ireland, very few census records for the 19th century survive. In the absence of written records, a detailed map helps fill the gap in the story of Bernard Trainor's life. The clipping shown, from volume 31, sheet 5 of the Townland survey of the counties of Ireland: maps published on the scale of six inches to a mile / engraved at the Ordnance Survey office (1832-1911) describes Strabane around the time the veteran would have left for the United States, and is a vivid link to his place of origin.

W.B. Clarke’s Map of Amsterdam describes the city in 1850. This is a good example of a map that works well with a census record, in this case the Amsterdam Civil Register of 1851-3. The register lists widower Moses Hamel, born 1814, and his children: Israel, born 1842; Betje, born 1844; Jacob, born 1846; and Naatje, born 1851. They live on Uilenburgerstraat, in the Jewish Quarter of Amsterdam known in Dutch as the Jodenbuurt, and we see the street in Clarke’s map.

During the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam during World War II, most Jewish residents of the city were removed from their homes and sent to concentration camps. Of the 80,000 people who lived in the city before the war, only 5,000 were living at the time of liberation in 1945. Many of the buildings in the Jodenburt were abandoned and became derelict, swept away during the re-development of Amsterdam in the mid 1970s, so now the area is very different. Clarke’s map survives as one record of the Jewish quarter in Amsterdam before the Holocaust.

Journeys

An Immigration Story

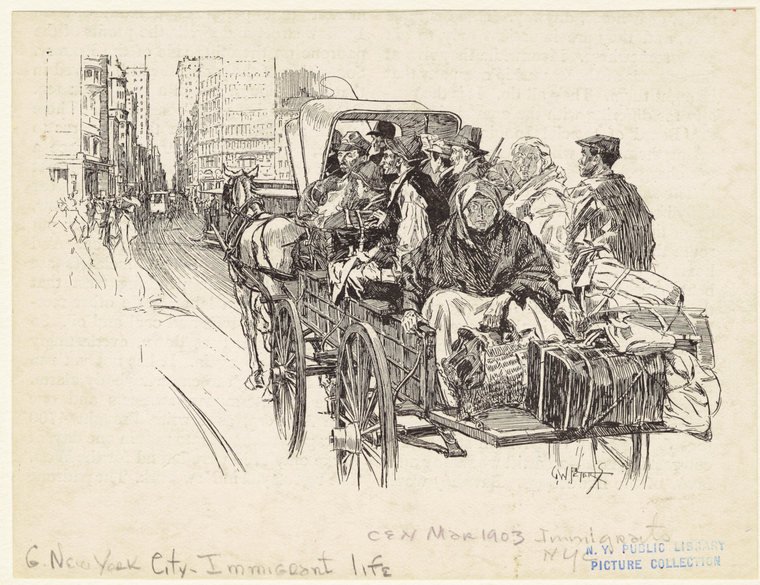

Stories about our ancestors come alive when illustrated with maps, photographs, and contemporary historical source materials to create narratives that engage with the reader.

For instance, let’s take an oral history from Passages to America : oral histories of child immigrants from Ellis Island and Angel Island by Emmy E. Werner and illustrate what is already a fascinating story with maps, photographs, and other documents available from collections at the Library and elsewhere.

In 1920, Marion Da Ronca, age 9, came to the United States from Vigo in Northern Italy with his mother Regina, 50, and his older sisters, Giovanna, 23, and Lina, 15. They were going to stay with Marion's oldest sister, Lena Gotta, who lived with her husband and their children in Iron Belt, Wisconsin.

The journey took approximately 15 days by horse-drawn carriage, four steam trains, two ferries, one ocean liner, and at least one bus. Marion described his journey in an interview conducted in 1992:

"The only thing we packed was our clothes. That’s all there was to pack. We travelled ten to fifteen miles on a horse-drawn carriage, then boarded a train to Padua [...] in Italy.[...] Then we boarded a train to Cherbourg, France."

![Town Plan of Cherbourg / U.S. Army Map Service, 1943 [detail] Town Plan of Cherbourg / U.S. Army Map Service, 1943 [detail]](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/cherbourg1941.jpg)

That boat was the RMS Adriatic, a steam passenger ship of the White Star Line, launched in 1907. It sailed from Southampton, England, to New York City, picking up passengers up at Cherbourg. The ship weighed 25,000 tons and held 2,825 passengers—1,900 in steerage, where Marion and his family would have been.

The NYPL Picture Collection features thousands of images of sail and steam passenger ships not available online, including photographs of the R.M.S. Adriatic shown in this post. Marion and his family are described in the manifest below: note that Marion's mother is traveling under her maiden name, Martini, something married Italian women commonly did at this time.

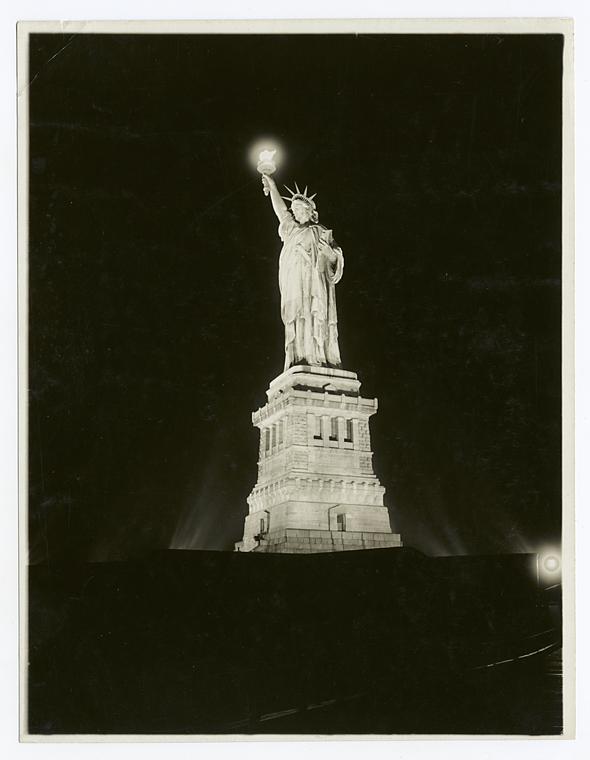

Many researchers wonder how their ancestors got to and from the immigration receiving station at Ellis Island once they had arrived at the Port of New York. Did steamships dock at Ellis Island? Or did ferries take immigrants there? How did immigrants get back to the mainland? And then on to their final destination?

Hagstrom's Map of Lower New York City, House Number and Subway Guide of 1920 identifies the names of the piers where the ocean liners of the various steamship companies docked, carriers like the White Star Line, Cunard, and the Hamburg-Amerikka Line (as shown). It also describes the routes of the ferries to and from Ellis Island (as shown), the locations of subways and trams that would take immigrants to relatives or to their new homes in Manhattan, Brooklyn, or New Jersey, for instance, and the location of railroad stations that would have transported passengers all over the United States.

Marion's story continues…"And the tugboats were waiting for us. They pulled alongside, and they pushed the boat right into port. Then they ferried us to Ellis Island."

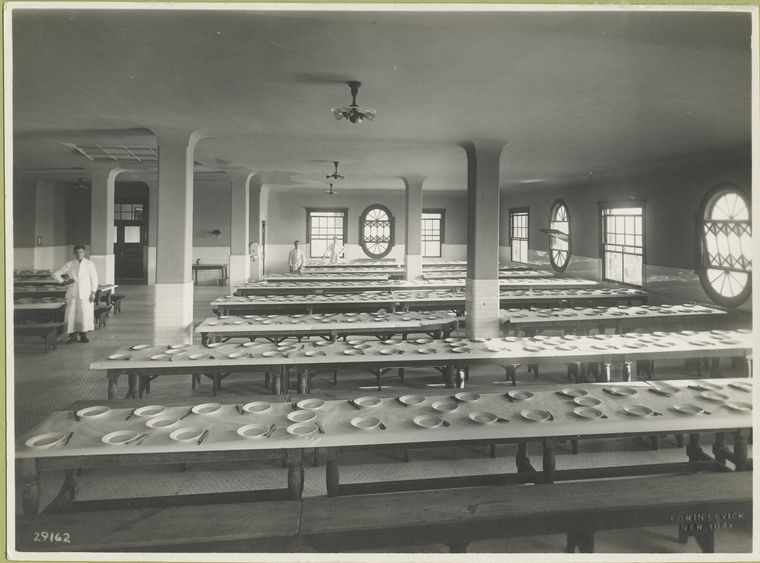

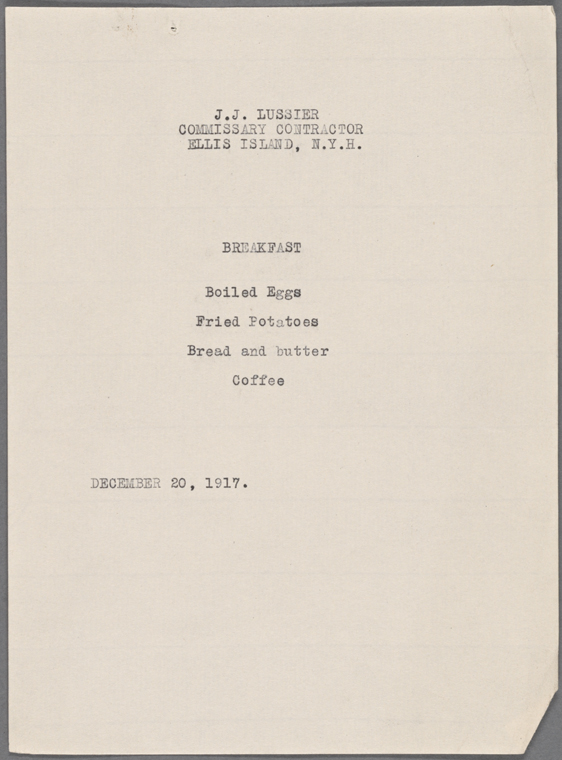

"We were all examined, and then we stayed overnight."

"We had four bunk beds. There was one for my mother, one for me, then one for each of my sisters, all in one room. And they were hard, covered with just a couple of blankets."

"We ate in the big dining room. My mother held me by the hand all the while. She never let go as long as we were there."

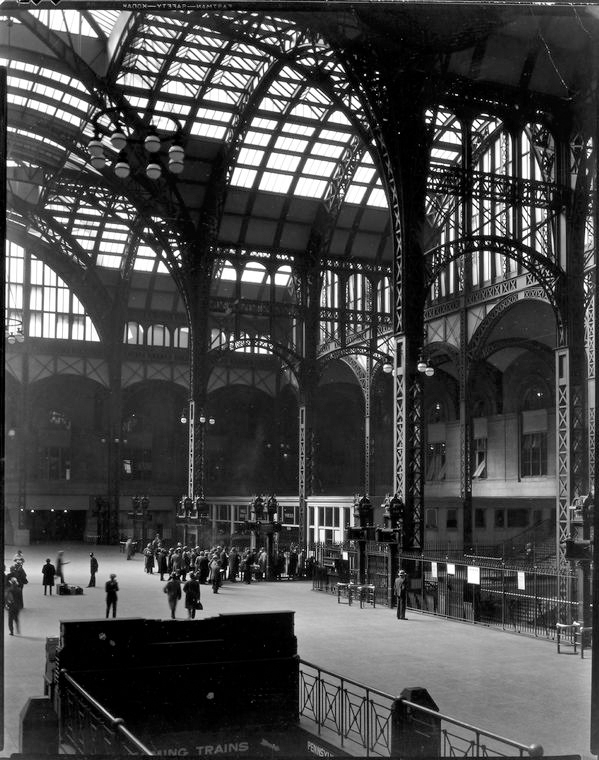

"When we left Ellis Island, we went back to the ferry and then took a train out from New York City to Detroit."

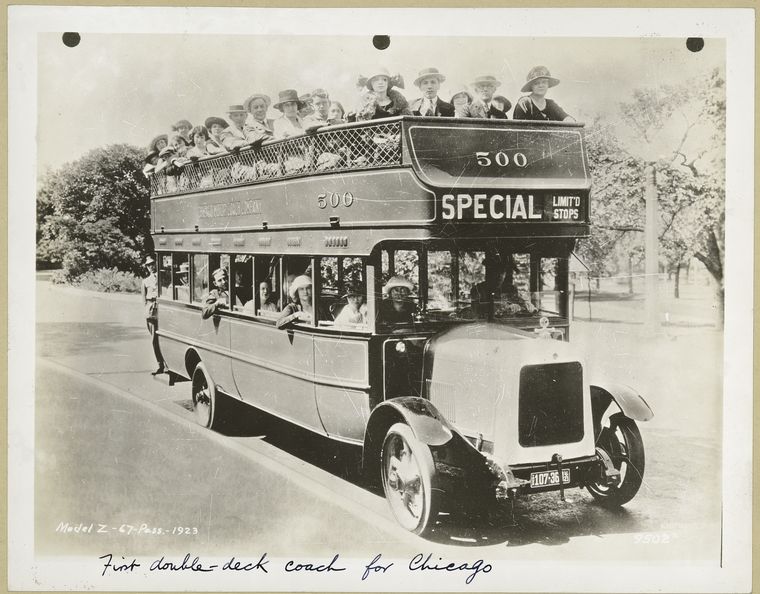

"We changed trains in Detroit and went to Chicago. In Chicago, they bussed us around the lake to the Northwestern Station…"

"… and from there we went to Hurley, Wisconsin. We stayed over at my sister’s. I went to school the following fall, and in about five to six months I was talking pretty good English."

The map featured, Plate 11 of the Sanborn Map of Hurley, Iron County, Wisconsin, published in 1922, describes the final destination of Marion and his family, the home of his Aunt Lena. Inset on the plate are two schools, possibly including the school that Marion attended.

Previous, Part 2: Fire Insurance Maps: Exploring Space and Time

Next, Part 4: Topographical Maps, and County Maps and Atlases

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.