Research at NYPL

The Library Enriches Its Photographic Collection on Sakhalin

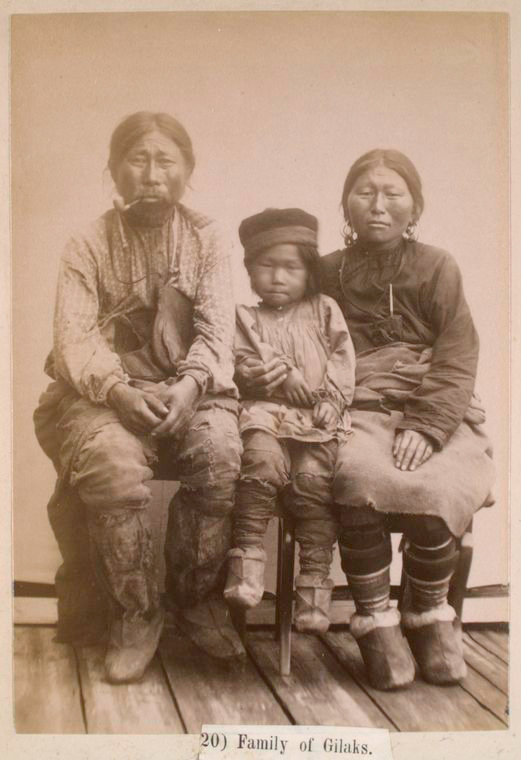

The New York Public Library holds an exceptional collection of visual materials, including photographs from pre-revolutionary Russia. In 1921, the Library acquired the archive of George F. Kennan (1845-1924) who traveled extensively in Siberia. An album of photographs of the penal colony of Sakhalin has captions written in a hand very similar to Kennan’s. It is called Sakhalin, the Island of Exile: Photograph Collection of the Russian Island Penal Colony during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. According to William C. Brumfield, 129 mounted photographs depict "administrative buildings, churches, local ethnic types, prisoners (some mention crimes, punishments), and convicts at work." Photos were numbered in no particular order, with English captions, with some corrections by a person (the photographer?) who was present during the photography and thus knew the subject matter/sites. Photos were presumably taken around the time of Anton Chekhov’s trip to Sakhalin who subsequently described it in his famous work Ostrov Sakhalin: iz putevykh zapisok (1895), later also published in English-language translations. These photos constitute remarkable materials from one of Russia’s most notorious penal colonies which at that time had a population of some 10,000 convicts and exiles and smaller numbers of indigenous Gilyak and Ainu.

The newly acquired album, Sakhalin photograph album, between circa 1885 and circa 1905 includes 108 original gelatin silver photographs of Sakhalin showing tsarist prisons, executioners and prisoners, post Alexandrovsky, post Korsakovsky, villages and settlements in Northern and Southern Sakhalin, early oil enterprises, Japanese fishing boats and fisheries, Japanese Consulate, Nivkh, Ainu, Tungus, and Orok People. One photo (“Gilyak summer yurt”) is signed “Фонъ Фрикенъ” (“Fon Fricken”) in negative. All but one photo include period ink captions in Russian on the mounts.

Below is a description of this album provided by the seller, Bookvica.

An extraordinary and historically important collection of rare original photos of the Sakhalin Island at the peak of its use as a Russian Imperial penal colony and place of exile for criminals and political prisoners. The Sakhalin katorga (servitude) system, largely based on the model of Australian penal colonies, operated in 1869-1906. Over this period, more than 30,000 inmates and exiles, including women, went through the system. Severe corporal punishments, such as flogging, shackles, and enchaining to wheelbarrows for several years, as well as executions, were widely practiced. After the completion of their term, the prisoners had to stay on Sakhalin as free settlers in the newly founded villages scattered across the island. By the end of the 19th-century, there were seven prisons on Sakhalin (Due, Alexandrovskaya, Korsakovskaya, Rykovskaya, Onorskaya, Derbinskaya, Voyevodskaya). The island and its katorga became famous after the publication of travel accounts by Anton Pavlovich Chekhov (Ostrov Sakhalin, 1895) and publicist Vlas Doroshevich (Sakhalin, 1902, in 2 parts). After Russia’s loss in the Russo-Japanese war (1904-05), southern Sakhalin became Japanese territory. The majority of the Russian population had to move, and south Sakhalin prisons closed. Sakhalin katorga officially ceased to exist in 1906, and the only working prison remained in Alexandrovsk.

Our album presents a rare detailed picture of Sakhalin in the early 20th century, showing prisons and exile settlements, prosecutors and prisoners, principal towns, fishing and oil extracting enterprises, ethnographical views, and portraits of the native people. The photographer was most likely Alexey von Fricken / Алексей Александрович фон Фрикен, a government inspector of agriculture on Sakhalin in 1888-1905 and the supervisor of the Sakhalin meteorological stations in 1889–92. Von Fricken was actively involved in the Sakhalin charity activities, published several articles in the “Sakhalin calendar” in 1896–97, helped to establish a local museum, and took part in the 1897 state census. He was also an amateur photographer and opened a studio in Alexandrovsk. During Chekhov’s visit to Sakhalin in 1890, von Fricken often accompanied him on trips and excursions and took a famous group portrait, featuring the writer and the Japanese consul near post Korsakovsky in southern Sakhalin.

The largest group of photos in the album—thirty—depict the Sakhalin katorga system. They include four explicit scenes of a prisoner’s execution (reading out the death sentence, putting the prisoner on the scaffold, hanging, taking the body off the gallows), and a horrifying photo of a body scarred after a flogging 17 years prior. There are also two portraits of famous Sakhalin executioners Golynsky and Komelev—both had long passages devoted to them by Doroshevich (“Sakhalin,” chapter “Palachi” [“Executioners”]), and a rare portrait of famous murderer Fedor Shirokolobov (1851–after 1899), sentenced to be attached to a wheelbarrow for ten years. The other portraits depict a prison trader, a group of prisoners sentenced to death for escape and the murder of guards, and a prisoner with half of his head being shaved to get the traditional look of a convict. Several photos show various facilities of the prison in post Alexandrovsky (jail for inmates with good behavior, punishment cells, the interior of the prison hospital, fire of the prison banya/bathhouse). There are also several portraits and scenes with prisoners—dragging a cart with flour sacks to the prison warehouse, employed in a shoe workshop, delivering wood, waiting near the warehouse to get working tools, fixing a road, quarreling over a card game, dragging logs on special carts to post Alexandrovsky, etc. The other “prison-themed” photos show post-Due taken from the sea, Vladimirsky coal mine, prison watermill in the Tymovsky district, the interior of the Onorskaya prison (apparently decorated for Christmas), prison mill in Vladimirovka village (Korsakovsky district), and a group portrait of “Chinese naval cadets exiled for the attempt of the explosion of gun powder warehouse in Port Arthur in 1900.”

Sixteen photos show post-Alexandrovsky, Sakhalin’s administrative center at the time. Among them are two views of the main street, images of the school, the house of the Alexandrovsky district’s head, the Bazarnaya square (general view and a view of the maidans/market stalls), the meteorological station and the police department, Bolshaya Alexandrovka River (two views, the second one featuring the prison warehouses), Alexandrovsky wharf in winter (two views, one featuring a well-dressed woman, likely the photographers’ acquaintance or relative), post and telegraph office in winter with dog sleds waiting for the post cargo, scenes of “arrival of the winter post to Alexandrovsky” (featuring the post office on the right, the whale skeleton next to the museum on the left and St. Nicholas chapel in the center), etc.

Sixteen photos show various locations in northern Sakhalin—Cape Zhonkier and Three Brothers rocks (including the new lighthouse at Cape Zhonkier built in 1897), a view from the Pilenga mountain range, Krasny Yar village (founded in 1889 in the Alexandrovsky district), Khamdasa the 1st village (founded in 1891 in the Tymovsky district), Khamdasa the 2nd village (founded in 1892 in the Tymovsky district), three views of the Onor village (founded in 1892, in the Tymovsky district) featuring the local church, fisheries on the Poronai River, forest fire on the Amurdan pass, “typical flora of the Tymovsky district,” etc. Two photos show the emerging oil industry on Sakhalin—“dugout house of oil prospector Kleie” and “oil lakes of northern Sakhalin.” German engineer F. Kleie started extracting oil in northern Sakhalin in 1898. Having obtained Russian citizenship, he founded a company that drilled for oil near Nurovo and Boatasino; the company operated in 1908—1914.

Twenty-four photos show southern Sakhalin. There are several views of various settlements and views in the Bay of Patience—Post Tikhmenevsky (Poronaysk since 1945), “Mogun-Kotan” village (Korsakovsky district), Mogun-Kotan River (Pugachyovka River since 1947), Ainu yurts in the Manue village, “Seraroko” village (Korsakovsky district), “Kresty” village, (founded in 1885, Korsakovsky district), Bereznyaki village (founded in 1886), Naibuchi village on the Naiba River (Korsakovsky district), Ainu village “Naiero,” etc. The other photos show Post Korsakovsky (double-page panorama, Japanese consulate, main street), and various settlements in the Aniva Bay—Savina Pad village, “fisheries of Kramarenko in Savina Pad, Korsakovsky district”; “ice storage of Kramarenko company in Pervaya Pad, Aniva Bay,” interior of Kramarenko’s ice storage in Pervaya Pad, etc. Several photos show Japanese fishing vessels and fisheries in southern Sakhalin—Japanese junks in the mouth of the Poronay River, Japanese kungas (a small sailing vessel) in the Bay of Patience, fisheries of Japanese “Ochiyama Kochitta” and “Nisimura,” “herring pomace workshop of Japanese “So-San,” drying herring pomace,” etc.

The album opens with 22 photos of the indigenous people of Sakhalin—Gilyak (Nivkh), Ainu, Tungus and Orok. There are studio portraits of men, women, and families, and views of a “Gilyak summer yurt,” a construction for drying fish, a cage for bear caught for a “religious fest,” “Gilyak cemetery,” two scenes of a ritual bear killing by Nivkh and Ainu people, Nivkh boats, Nivkh making fire, Orok and Ainy yurts, a portrait of a “Tungus missionary,” and a view of the Sochigar village on the Poronay River in the southern Sakhalin where Ainy, Nivkh and Orok fishermen lived side by side.

The album opens with 22 photos of the indigenous people of Sakhalin—Gilyak (Nivkh), Ainu, Tungus and Orok. There are studio portraits of men, women, and families, and views of a “Gilyak summer yurt,” a construction for drying fish, a cage for bear caught for a “religious fest,” “Gilyak cemetery,” two scenes of a ritual bear killing by Nivkh and Ainu people, Nivkh boats, Nivkh making fire, Orok and Ainy yurts, a portrait of a “Tungus missionary,” and a view of the Sochigar village on the Poronay River in the southern Sakhalin where Ainy, Nivkh and Orok fishermen lived side by side.

Seven photos from the album illustrated the book of Nikolay Lobas about Sakhalin’s katorga and penitentiary system (Katorga i poseleniye na ostrove Sakhaline, Pavlograd, 1903), namely: “Post Due” (p. 21), “Quarrel during a card game” (p. 61), “Khamdasa the 2nd village” (p. 96), “Mogun-Kotan village” (p. 114), “Post Tikhmenevsky” (p. 149), “Bereznyaki village” (p. 154), “Savina Pad village” (p. 158). Nikolay Lobas (1858– after 1917) worked on Sakhalin as a doctor in 1892–1899 and was closely involved in charity work on the island. In 1913 he published a monograph about the psychology of murderers based on his observations made in Sakhalin (Ybuytsy: Nekotorye cherty psikhofiziki prestupnikov, M., 1913).

Overall a unique, extensive collection of rare original photos showing Sakhalin and its penitentiary system in the early 20th century. Although the presentation inscription is mostly removed, its remnants allow us to suggest that the album was compiled for Ivan Alexandrovich Krasnov, whose photographs of Sakhalin are now stored in the “Historical and Literary Museum Chekhov and Sakhalin” in Alexandrovsk, Sakhalin (https://www.wdl.org/ru/item/20094/).

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.