Land of the Unknown: A History of Hart Island

“To me, this island is like a huge monument surrounded by water. I call it the Land of the Unknown, because only God knows the full history of this island.” —Albert Carrasquillo, Pito, Hart Island Prisoners’ Statements

New York City’s Hart Island has served a morbid mix of purposes over the years, many of which sound like rejected settings for a season of American Horror Story. The grim list includes a prisoner-of-war camp, a workhouse, a tubercularium, and a prison. Used primarily as a place of burial for unclaimed, deceased New Yorkers, also known as a potter’s field, nearly a million of New York’s poorest, unidentified, and forgotten residents have been buried there since the mid-nineteenth century. It recently returned to the public eye as the site of a modern mass grave, a temporary resting place for victims of COVID-19. But the sad history of Hart Island is only part of the story.

Bare-knuckle Brawling

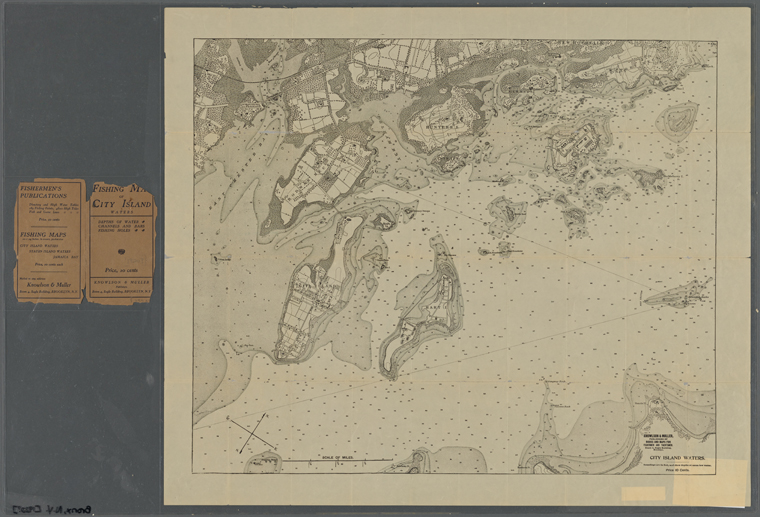

The land was originally purchased by Thomas Pell from the Siwanoy indigenous people, and the ownership of the island has passed piecemeal through many hands, with many different ideas about how to use it. Its remote location east of City Island made it a popular site for bare-knuckle boxing matches, out of the reach of police who might take issue with drunkenness, gambling, and a bit of hooliganism. A particularly popular grudge match in 1842 between James “Yankee” Sullivan and Billy Bell drew more than six thousand of New York’s less reputable residents to the island, or as the New York Daily Express put it, “A gang of loafers and rowdies went out of the city yesterday to see a fisticuffins.”

Red, White, Black, and Blue

The first public use of the island became necessary during the Civil War. The 31st Infantry Unit of U.S. Colored Troops began using the site as a training ground and barracks. This unit served in Virginia and was present at the final defeat of General Lee’s forces in April 1865. Later in the war, the island was used as a prisoner-of-war camp, notorious for its miserable conditions, as well as a burial ground for Union Army soldiers. While the remains were eventually moved, a monument was erected by the Army Reserves in 1877 to mark the location of the Soldier’s Plot.

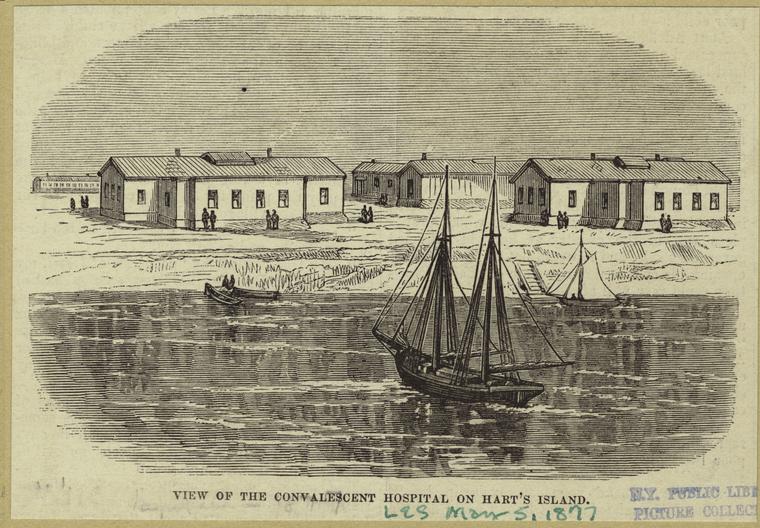

A Series of Unfortunate Events

Post-Civil War, the land was repurposed several times over. First, as a host for the Industrial School for Destitute Boys, essentially a workhouse for incorrigible and truant boys. There was also a men’s workhouse, a psychiatric hospital, and a quarantine site during the yellow fever epidemic. Hart Island began to be used in 1869 for city burials starting with 24-year-old Louisa Van Slyke, who the New York Times reported “was born at sea and died alone at Charity Hospital.” She was buried in the 45-acre public graveyard in a plain pine box, and she would soon have company.

Never Built New York

Solomon Riley had completely different ideas about what could be done with Hart Island. A native of Barbados, Riley made his fortune in real estate, buying properties on predominantly white streets in Harlem and renting to Black tenants. When a four-acre tract of land went up for sale on Hart Island, Riley jumped on it, announcing his plan to build a “Negro Coney Island.” The playland would cater to people barred from “whites only” amusement parks in Rye and Dobbs Ferry. Planning a grand opening on the Fourth of July, 1925, Riley oversaw the construction of a boardwalk, bathing pavilion, boarding houses, and dance hall. The city was not pleased. To keep Riley from opening the park, the land was condemned and purchased by the city for $144,000.

Government use of the island resumed with the installation of Navy barracks during WWII, and a Nike missile base in 1955. The supersonic missiles were stored underground and functioned as a defense against air attacks until the army closed the base and relocated six years later.

The New York Times, November 26, 1927

Dancing on the Graves

The next incarnation of Hart Island somewhat fulfilled Solomon Riley’s dream of gathering and entertaining crowds. Phoenix House, a drug rehabilitation program, held massive festivals and events like carnival rides and movie screenings, and drew big name musicians like The Velvet Underground and Janis Ian. Thousands of people made the ferry ride to the island for these events, until Phoenix House relocated to Manhattan in 1976.

Resting Place of Last Resort

The chaos and fear of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and '90s caused a spike in the island’s burials as many funeral homes refused to accept the bodies. Stigmatization and rejection led Hart Island to become “perhaps the single largest burial ground in the country for people with AIDS,” as The New York Times reported in 2018. Unlike other burials, those who died of AIDS were interred individually, 14 feet deep. The first child victim of AIDS to be buried on Hart Island is remembered by a stark, chilling marker which reads “SC-BI, 1985,” or Special Child, Baby 1.

The only witnesses to these quiet burials were the Rikers Island inmates who serve as both pallbearers and gravediggers, a practice which continues to this day. These incarcerated men are paid 37 cents an hour to unload pine caskets, mark them with a number and surname, lower them into the long mass graves and cover them with dirt.

Gone But Not Forgotten

Grieving the dead is central to the human experience, but those with loved ones interred on Hart Island have been denied the chance to visit their graves. Access to the island is restricted, and there are scant resources to identify unnamed burials. Once a month, friends and family can schedule an appointment in advance to visit a gazebo by the dock. Advocates are seeking to improve this process. A number of lawsuits have challenged the city to provide gravesite visitation rights, and with the island’s imminent transfer from the Department of Corrections to the Parks Department, things may become significantly easier for the bereaved.

Further Research:

-

Hart Island Potter’s Field | records, 1977-present

-

Hart Island history | Department of Correction

-

Hart Island Data | City Council

-

Hart Island Burials NYC Open Data | Department of Correction

-

About Us | Hart Island Project

-

Hart Island Frequently Asked Questions | Department of Correction

-

Hart Island | New York Times article

-

The History of Hart Island: A Place of Strangeness and Sorrow | The Bowery Boys

NYPL Resources:

- New York City’s Hart Island: A Cemetery of Strangers by Michael T. Keene

- Hart Island by Melinda Hunt and Joel Sternfeld

- The Other Islands of New York City by Sharon Seitz and Stuart Miller

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Land of the Unknown: A History of Hart Island

Submitted by tim p tureski (not verified) on January 13, 2021 - 2:36pm