Understanding Robert Douglass’s Reshaping of Visual Narrative About Black People in 19th Century America from a Multiliteracies Perspective

Researching artist and activist Robert Douglass Jr., one cannot help but consider his contribution to changing the narrative about Black people in 19th century America's visual culture. Born in a middle class Black family, Douglass was part of the free Black elite in Philadelphia. In his commitment to countering whites' degrading beliefs about African Americans, he founded a literary society to train free Black elites, and also used art toward this aim. Douglass experienced discouragement and racial discrimination, yet his incredible talent and perseverance evidence his desire to show Black people his various abilities.

Douglass's artistic activism and promotion of Black people's progress was evidenced in his conception and diffusion of abolitionist visuals, and in his 1833 oil painting of William Llyod Garrison, the white abolitionist and friend of his family. Still, Douglass’s contribution in reshaping the visual narrative about black people in 19th century America was enhanced and informed by his international travels. In 1837, he traveled to Haiti where he spent 18 months. During his time there, he painted, learned about the culture, and associated with important citizens and artists (Jones, 1995). In 1840, he went to Europe at a time when the French artist, Louis Daguerre, was introducing an innovative process for reproducing photogenic images that pioneered photography, later known as daguerreotype. Most of Douglass’s work has not survived. However, to examine his participation in changing the narratives about Black people in his time, I focus on the narrative description related to his trip to Haiti; the lithograph modeled on his painting, and some portraits identified as his work.

Multilteracies Framework

Images are a form of meaning-making different from print and written texts, and have been used by humans to communicate meaning (Lundy & Stephens, 2015), and make sense of their experiences and environments. To engage with and understand Douglass’s contribution in reshaping the narrative about Black Americans, I build on the multiliteracies perspective on literacy, which defines literacy beyond reading and writing. The multiliteracies framework views literacy as involving multiple modes of meaning-making including “visual, gestural, spatial, and other forms of representations” (Perry, 2012, p.58). Images are not mute (Campt, 2017), but rather a specific language that draws on and is situated in the sociocultural context in which the images are created and presented. Repurposing Campt’s (2017) argument to “listen to” rather than “look at” images as sound in order to deeply engage with the overlooked histories that these images convey, I contend that “making sense” of images created by Black Americans with Black people in the 19th century provides a sociocultural context, unravels the meaning these images conveyed, and the creators’ understanding/reading of their environment/ condition. Hence, in the following section, I engage with Douglass’s work from a multiliteracies perspective to interpret and make sense of the paintings, lithographs, daguerreotypes, and banners he created or inspired.

Making Sense of Robert Douglass's Work

In 1841, Douglass scheduled lectures where he displayed paintings from his Haitian journey at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia. The work displayed included:/p>

- A painting of Joseph Balthazar Inginac, the secretary general of Haiti

- Grand Picture representing the anniversary of Haitian Independence, with views of government buildings, monuments and forts and more than 200 figures

- Portraits of Haitian Ladies, displaying their costume (Gonzalez, 2014; Jones, 1995)

- And a portrait of Douglass by Haitian artist Colbert Lochard (Jones, 1995)

Though most of these paintings were lost, one can get a glimpse at how he portrayed Haitians in the detailed description included in Douglass's letter to the Liberator on February 9th, 1838, titled the “Commemoration of Haytien Independence.” He wrote:

I must say something of the anniversary of Haytian Independence, which was celebrated this day. In fornt of the Government House was a platform, on which was the President, Inginac, and other distinguished officers, surrounded by the lawyers, pupils of the different schools, and about 6000 of the military…. The President’s seat was canopied with crimson silk., ornamented with golden tassels and fringes; and each side of him stood a soldier of his guard, with a drawn sword. Nearly in front of him stood Rouanez, one of his Aide-de-Camp; immediately behind him, a group of fine looking officers. His Excellency was dressed in a blue frock coat, thickly embroidered with gold. Across his shoulder he wore a sash of velvet and gold, to which was appended a most splendid sword. When walking, he wore a very large ‘chapeau a la elaque’ altogether presenting a brilliant appearance. He is quite small in figure, and thin visage, with piercing black eyes, which he moves with extraordinary rapidity. He is remarkable for the gracefulness of his movements, and presents an admirable appearance on horseback. On his left, in a seat also distinguishable from the mass, sat Inginac, the Secretary General – quite an old gentleman, with his hair whitened by age, and wearing a splendid uniform. He is of so light complexion, that a stranger would suppose him to be a white man. He is called the Talleyrand of Hayti, and I presume that his memoirs and History of the Island, (not to be published until his death,) will be nearly as interesting as those of the French diplomatist. Farther to the left, on the opposite side sat the Senators, fifty or sixty in number, fine looking men.…I had never seen so many soldiers, and the perfect regularity of their movements amazed me. They were well armed, and, with few exceptions, well equipped and the appearance of the ‘Garde National’ or military horse and foot, was truly splendid. …. What I have seen to-day, I shall not soon forget; for although too much of a peace man to approve of a military government, yet the sight of what these people have arisen to, from the most abject servitude caused in my bosom a feeling of exultation which I could not repress.

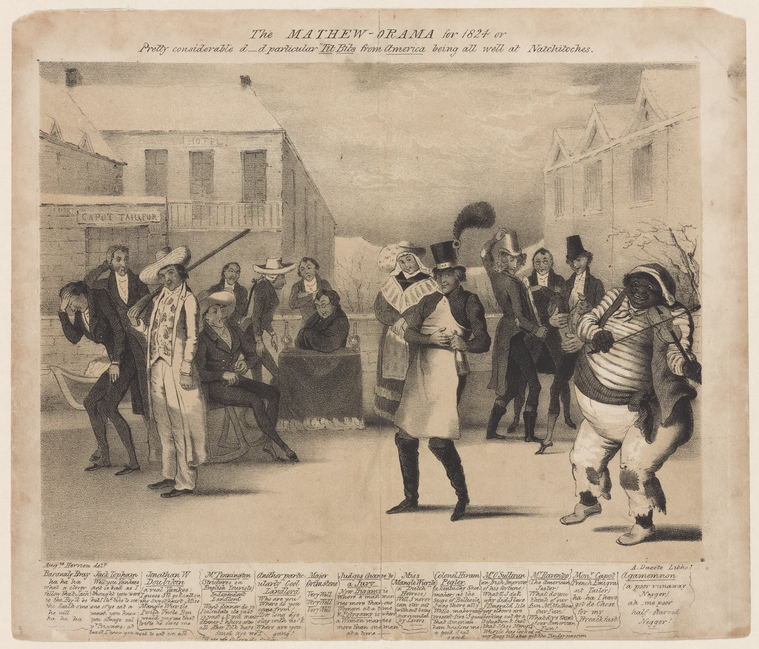

From this letter, it is clear that Douglass’s portrayal of Haitians in his paintings contrast the popular depiction of Black people in the American visual culture of the 19th century. The brilliant appearance, the elegant dressing, the handsomeness, and the nobility of these Black Haitians opposed the racial and degrading representations that projects the inferiority of Black people in America (Figure 1).

Based on the letter to the Liberator, Douglass’s paintings of Black Haitians exhibited at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia on April 9th, 1841 certainly communicated the prowess, abilities, and aspirations of Black people. These portraits, as Douglass wrote, showed how Black people were able to rise from horrible conditions of slavery. Moreover, the paintings situated Black people's experiences within the sociocultural context of the 19th century, while pushing against the perception of Blacks as inferior, unorganized, only able to work under the harsh conditions of slavery. Through these images, Douglass also transmitted his understanding of what it meant to be Black. Black meant beauty, freedom, excellence, rejection of servitude, imposed social status, and identity. His artistic activism served two purposes: reclaiming Black identity among Black people, while countering popular narratives about Blacks in the collective minds of Americans. The excerpt below, written in the National Anti-Slavery Standard journal2 on April 12th, 1841 titled “Lecture on Hayti”, further gives insights into the meaning of Douglass’ artistry.

We intended last week to mention the lecture of our friend Robert Douglas, Jr, on Hayti- its discovery, history, condition, and the manners and character of the people. It was given on the evening of the 16th [st] at the vestry room of St Thomas Church, and afforded evident gratification to an audience which, though respectable, was much smaller than we should have been glad to have seen present. The lecture conveyed much interesting information, and was agreeably illustrated with portraits of distinguished Haytiens, sketches of Haytien costumes, scenery, &c. Pa Freeman.

The paintings, as the reporter wrote “afforded evident gratification to an audience which, though respectable, was much smaller than we should have been glad to have seen present.” Douglass challenged Blacks’ perception of themselves, and prevailing depictions of Black people in American visual culture. He confronted the dominant white American minds with the humanity, beauty, identity, aspiration, and achievement of Blacks. For instance, a banner, which scholars believe he probably designed for the Young Men's Vigilant Association of Philadelphia for a parade celebrating Jamaican Emancipation Day, caused white males to attack these Black males on August 1st, 1842 (Jones, 1995). Jones (1995) described the banner as follows:

The banner showed a Negro male pointing with one hand to broken chains at his feet and with his other hand to the word "liberty" in gold letters above his head, along with the rising sun and a sinking ship, emblematic of the dawn of freedom and the wreck of tyranny (p.12).

Prior to the 1840s, Douglass portrayed eminent African Americans such as James Forten (Figure 3), one of the wealthiest African Americans in the 19th century. Forten used his wealth to advocate for the emancipation of fellow African Americans, and rectify the injustices they experienced (Winch, 1997). As seen below, James Forten’s portrait conveyed sophistication, social status, achievement, intelligence, and confidence. This wasn’t a fearful Black man, who appeared confused, with no vision or purpose. In the midst of racial discrimination, Forten’s body orientation in the painting revealed determination, and focus. Moreover, the orientation of his body (head, gaze, and body slightly turned away from the viewer), indicated that opponents to Black people’s freedom and the racist structural systems could not distract from Black people’s pursuit of freedom and self-determination. Indeed, in this portrait, Forten does not gaze directly at the viewer, which may indicate that the sitter was a) engaged with something else than the viewer (White, 2019); or b) did not need to attract the viewer’s attention because he was already famous (Morin, 2013). Douglass in collaboration with Forten must have agreed on a set of standards for pose, and expression suitable for a nobleman in an image designed for public display in their sociocultural context (White, 2019). For this reason, I contend that the portrait also communicated self-sufficiency, while providing meaning to the Black experience and struggle in the 19th century.

The daguerreotype portrait of Francis/Frank Johnson, a successful Black musician and bandleader, by Douglass sometime before 1844 (Gonzalez, 2014), also captured the essence of Douglass’s visual activism in transforming the perception and representation of Black people in American visual culture. The daguerreotype, inspired a lithograph by artist Alfred Hoffy (Figure 4), showed a Black man seated, facing the viewer, holding a trumpet in one hand “and resting his other arm on a table [with] music sheet, a quill, and an inkwell” (Gonzalez, 2014, p. 31). This full portrait drew the viewer to Frank Johnson’s profession and abilities. He was a composer and a bandleader. The frontal orientation of the body, head (slightly tilted to the left), and gaze (eyes looking directly at the viewer) depicted confidence, and readiness to interact with the viewer. This painting of a highly talented Black man conveyed success; indicated social status; his Black identity with a kind of ‘low taper afro hairstyle’, and his ability to read and write. Commenting on this lithograph, Gonzalez (2014) stated:

composer’s slightly tilted head and the expression of ease and warmth on his face lend him an air of friendliness. The lithograph draws attention to Johnson’s aptitude as well as to his professional success, further evidenced by his middle-class attire. Th is is an image of Black success, respectability, and intelligence (p.31).

Douglass’s portrayal of Blacks was an indication of his activism, love for his race, and contribution in reclaiming as well as pointing to the identity, humanity, aspirations, and intelligence of Black people. With his work, Douglass engaged in meaning-making about Black experiences and achievements in the 19th century. From the Haitian depictions to Frank Johnson’s portrait, Douglass engaged the viewer in literacy practices that confronted and openly critiqued the racialized literacy about Black people in the minds and culture of 19th century America. Using the multiliteracies framework to interpret Douglass’s work not only shows the historical relevance of his work in literacy scholarship, but also situates his work in the contemporary understanding of literacy, and what it means to be literate. Our current society is image-driven; exploring diverse literacies, prior to the 20th century can expand literacy studies today.

Read more: Robert Douglass Jr., 19th Century African American Artist

Footnotes

1 The Mathew-orama for 1824, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, Prints Depicting Dance Collections. Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

2 Official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society, established in 1840 under the editorship of Lydia Maria Child and David Lee Child. Found in Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

References

Douglass, R. (February 9, 1838). Commemoration of Haytien Independence. The Liberator, 8(6), Retrieved from http://fair-use.org/the-liberator/>

Frank Johnson. Lithograph by Alfred Hoffy, from a daguerreotype by Robert Douglass, Jr. (Philadelphia, 1846). Historical Society of Retrieved from https://librarycompany.org/blackfounders/section9.htm

James Forten (1834). Leon Gardiner collection of American Negro Historical Society Records , Historical Society of Pennsylvania,. Retrieved from https://librarycompany.org/blackfounders/section9.htm

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. (1824). The Mathew-orama for 1824. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/69ebd3d0-f8d0-0132-08f5-58d385a7b928

Jones, S.L. (1995). A keen sense of the artistic: African American material culture in nineteenth-century Philadelphia. International Review of African American, 2(12), 11-29

Lundy, A. D., & Stephens, A. E. (2015). Beyond the literal: Teaching visual literacy in the 21st century classroom. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174, 1057-1060.

Morin, O. (2013). How portraits turned their eyes upon us: Visual preferences and demographic change in cultural evolution. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.01.004

National Anti-Slavery Standard. (1840-1870). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division. Retrieved from Readex: America's Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/readex/doc?p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A158B8D5FF09794C6%40EANX-15C3F2BFA8D30CC0%402393597-15C3E45E08FC9D08%401-15C3E45E08FC9D08%40

Perry, K. H. (2012). What Is Literacy?--A Critical Overview of Sociocultural Perspectives. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 8(1), 50-71.

White, P. A. (2019). Body, head, and gaze orientation in portraits: Effects of artistic medium, date of execution, and gender. Laterality: Asymmetries of Body, Brain and Cognition, 1-33. doi:10.1080/1357650x.2019.1684935

Winch, J. (1997). "You know I am a man of business": James Forten and the factor of race in Philadelphia’s antebellum business community. Business and Economic History, 26(1), 213-228. Retrieved April 5, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23703308

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.