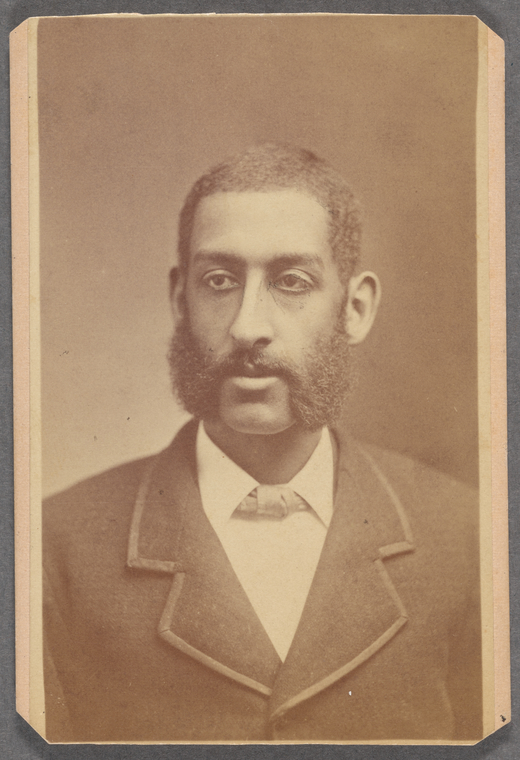

Robert Douglass Jr., 19th Century African American Artist

Robert Douglass Jr. was born in Philadelphia in 1809 into an activist family that emigrated from the Caribbean island of St Christopher/St Kitts. His father, Robert Douglas Sr. was an officer of the Pennsylvania Augustine Society for the Education of People of Colour, who opposed the American Colonization Society effort, started in 1816, to repatriate free African Americans to Africa. His mother, Grace Bustill Douglass, was an abolitionist, whose influence was felt in the political and artistic work of her daughter Sarah Mapps Douglas. Robert Douglas Jr’s two siblings Sarah Mapps Douglass (older sister), and William Penn Douglas (his younger brother) were artists, and activists who also followed the family anti-slavery activism tradition.

Robert Douglass (Figure 1) studied portrait painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with Thomas Sully, the renowned painting artist of the time. Douglass was a painter, printmaker, and photographer. Though his first work was an oil painting of the Pennsylvania State seal, he rose into public prominence with his transparencies of President George Washington Crossing the Delaware. This artwork was displayed on Independence Hall to celebrate the centennial of Washington’s birth on February 22, 1832. Douglass experienced discrimination at art exhibitions in Philadelphia where racism against African Americans was commonplace and whites considered it normal. For instance, in 1834, Douglass’ oil painting Portrait of a Gentleman was included in the annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. However, he was prevented from getting into the Academy to view his own work because of his race.

International Travels

In 1834, violent racial street riots started in Philadelphia by white males. African Americans were attacked, their houses looted and destroyed in actions these white males described as “hunting the nigs”. Racial tensions continued and grew worse in the following years. It is during this period of intensified racial violence that Douglass traveled abroad. From 1837-1839 he was in Haiti, where he interacted with respected politicians and artists (e.g., Joseph Balthazar Inginac and Colbert Lochard). In 1840, with recommendation letters from his former instructor at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Thomas Sully, he was admitted at the National Gallery in London, where he studied. Despite the rejection of his application for an American passport by the US Secretary of State because “the people of color were not citizens and therefore had no right to passports to foreign countries1”, the French and British allowed him to stay and travel in Europe. This created an opportunity for Douglass to learn how to produce daguerreotypes, a revolutionary process of photography introduced by Frenchman Louis Daguerre. In 1847, in a period characterized by racial violence, Douglass as many other African Americans, left Philadelphia. He traveled to Jamaica, where he likely had citizenship given his father’s Caribbean background. However, in a letter to Sidney Howard Gay dated February 29, 1848 and published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard on April 20, 1848, he wrote:

great numbers of the lower orders running to and fro, almost all Black… who are fond of amusing themselves by the beating of drums ... singing and dancing, keeping up such a perfect discord that it was exceedingly difficult to get any sleep2.

After a few months in Jamaica, Douglass returned to Philadelphia, the city of his birth, where he died in 1887.

Work

Douglass’s artistic skills were exhibited in the paintings, banners, lithographs, and daguerreotypes he created or inspired including:

- A banner3 designed for the Young Men's Vigilant Association of Philadelphia, displaying a Black male with one hand pointing to broken chains at his feet, and his other hand pointing to the word "liberty” written in gold letters above his head. He added the rising sun and a sinking ship which symbolized the birth of freedom and the end of tyranny.

- Oil painting of the Pennsylvania state seal.

- Painting of George Washington Crossing the Delaware4 displayed on Independence Hall in Philadelphia to celebrate the centennial of the first president's birth.

- Painting of William Lloyd Garrison, the white abolitionist from which he made lithographs5 for mass marketing

- A watercolor paint of a three-quarters view of a kneeling female slave in Mary Anne Dickerson6 scrapbook

- Portraits of Haitian Ladies, showing their Costume

- Painting Joseph Balthazar Inginac, the secretary general of Haiti.

- Daguerreotype portraits of popular figures such as Frank Johnson7, Abby Kelley Foster8,

- Grand Picture of the Haitian Independence anniversary of January 1st, 1839

- Painting titled “Magnanimity of a Great Artist” in 1876 included in the Pennsylvania Academy annual exhibition, which may have been the portrait of Frederick Douglass

- Oil portrait of Henrietta Bowers Duterte9

- Portraits copied from paintings in the National Gallery in London10

- Portrait of Frederick Douglass presented at the Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1878.

-

Douglass’ talent was undeniable as shown with the inclusion of his work in the Pennsylvania Academy annual exhibitions11, and by reports in journals. For instance, writing about Douglass’ exhibition on Haiti, a reporter of the National Anti-Slavery Standard12 journal13 wrote:

These were from the pencil of the lecturer himself, whose skill as an artist is highly creditable to his talents and perseverance under all the discouragements to which one his complexion is exposed, whenever he engages in any except what are generally considered the lower and less respectable occupations.

Most of Douglass’s work did not survive. The American Antiquarian Society, in Massachusetts, has a daguerreotype of the abolitionist leader Abby Kelley Foster (Figure 2 ). The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has Douglass's lithograph of the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, (Figure 3) as well as a lithograph of the Black musician Francis Johnson (Figure 4).

-

Figure 3. Lithograph portrait of William Lloyd Garrison, facing viewer, with glasses, a black-colored neckwear and suit by Robert Douglass, Jr. dc-865 Historical Society of Pennsylvania portrait collection (#V88). Digital Library. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Figure 4. Lithograph portrait of Frank Johnson14, a man seated facing viewer in a dark-colored suit, holding a trumpet in one hand. Created from a daguerreotype by Robert Douglass Jr. Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania In addition to his artistry, Douglass was engaged in the Anti-Slavery Society, taught drawing and painting along with his sister (Sarah) at The Institute for Colored Youth; founded the Philadelphia Library Company of Colored Persons in 1833 with the goal of developing knowledge of literature, science, public-speaking and debating skills among its free Black males. Douglass also wrote reviews of the Centennial for the Christian Recorder15 , the first and only Black newspaper to have a continuous circulation for one hundred years, defending American Art.

Douglass was the first African American artist whose work was included in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts Annual exhibition in 1834, but could not live off his work, and struggled financially. Yet, he inspired artists such as David Bustill Bowser, his nephew, and one of Philadelphia’s most commercially successful African American artists of the 19th century, and paved the way for others centuries after.

Read more in this series, Blacks Reshaping Narratives About Black People in 19th Century America:- Flora Stewart: African American Woman, Oldest Citizen of Londonberry, N.H

- Considering Flora Stewart’s Portrait as an Autobiography of an African American Woman

Footnotes

* Cartes de Visite Collection (US), 19th Century Collection, Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

1 Pryor, E. S. (2017). Colored travelers: Mobility and the fight for citizenship before the Civil War. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

2 Quote found in Modern Negro Art, (pp. 168-169), Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

3 Jones, S.L. (1995). A keen sense of the artistic: African American material culture in nineteenth-century Philadelphia. International Review of African American, 2(12), 11-29

4 Was exhibited on February 22, 1832, and was painted on a translucent substance, possibly a paper or lightweight cloth, such as silk, linen, calico or muslin. The artificial or brilliant lights placed behind the painting illuminated it giving it a bright effect.

5 Method of printing through a metal plate also used by artists to produce prints of works intended to be sold in many copies.

6 A young middle-class African American from Philadelphia whose scrapbooks were a combination of scenic views, poems, prose, essays, and drawings on topics such as friendship, motherhood, mortality, youth, death, flowers, female beauty, and refinement.

7 Famous African American composer and trumpeter, who led a band in Philadelphia around 1846, toured the United States and England. Helen Armstead-Johnson miscellaneous theater collections (1831 – 1993), Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

8 White abolitionist, friend of Douglass’ sister, Sarah Mapps Douglass, Abby Kelley Foster, 1899, Personal reminiscences of the anti-slavery and other reforms and reformers. Aaron M. Powell Collections, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

9 First African American, and woman owner of a funeral home in the nation who participated in the Underground Railroad by helping runways safe passage through coffins. African Americans- Pennsylvania--History: clippings, Sc VF: Part 3, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

Jones, S.L. (1995). A keen sense of the artistic: African American material culture in nineteenth-century Philadelphia. International Review of African American, 2(12), 11-29

10 An ad in the National Anti-Slavery Standard journal of February 24, 1842, p.3 in the Notice section reads: "R. Douglass, jr. will deliver a lecture on painting, in the Union Hall, basement of the Tabernacle, in Anthony street, on Monday evening, February 28th. The lecture, to commence at 8 o’clock, will be illustrated with paintings, copied by R. Douglass, jr. from the great masters in the National Gallery, London-portrait of Cingue the hero of the Amistad". Excerpt, from 1842, February 24. National Anti-Slavery Standard, p. 3. Retrieved online from Readex: America's Historical Newspapers through New York Public Library

11 Due to racial discrimination, Douglass was prevented from viewing his own work in the Academy because of his skin color

12 1841, May 6. National Anti-Slavery Standard, p. 2. Retrieved online from Readex: America's Historical Newspapers through New York Public Library

13 The National Anti-Slavery Standard was the official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

14 A portrait can also be found in the Joseph Muller collection of the New York Public Library

15 Found in the Collection of The Philadelphia colored directory, 1910: a handbook of the religious, social, political, professional, business and other activities of the Negroes of Philadelphia, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture,

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.