How to Achieve Spiritual Perfection in 30 Easy Steps

All the Library's holdings are of course treasures, although some are more treasurable than others. While I'm working from home, I thought I would write about some of the treasures great and small that have passed through my hands in recent months as a rare books cataloger.

First up is a 1492 Venetian edition of Scala Paradisi (Latin for "The Ladder of Paradise") in the Library's Spencer Collection. This is not a very beautiful nor a very uncommon volume, but it has its fascinations—like all printed books produced before 1501, while the art of printing was still in its cradle. Specialists fondly refer to these books as incunabula, or cradle books.

The author is a sixth-century Syrian revered as a saint by three branches of Christianity, and generally known in the English-speaking world, for his most famous work, as Saint John Climacus, or "John of the Ladder."

You wouldn't expect a guy who lived that long ago to be the subject of a Wikipedia war, but so it is. In brief, up to the twentieth century, everyone unquestioningly believed him to be a writer of the sixth century. But in the twentieth century scholarly opinion shifted him forward to the seventh century . . . and now, in the twenty-first century, has shifted him back.

The original Catholic Encyclopedia (1910) has the traditional dates, which are once again the accepted ones: born "about 525," died "probably in 606 . . . others say 605." But the New Catholic Encyclopedia (2003), has him as "b. 579; d. 649," dates accepted for most of the previous hundred years but no longer considered correct. (See Resources, below.)

This is reflected in Wikipedia. The most recent revision of his entry (March 27, 2020, as of this writing) has the later dates, but some previous versions have instead the traditional and currently accepted earlier dates. The choice of dates has apparently depended on whether the Wikipedian was relying on the old or the New Catholic Encyclopedia. Moral: New isn't always better.

As the original Catholic Encyclopedia describes the saint, he lived by choice the way many of us are now living out of necessity (we hope, for a much shorter period of time):

Although his education and learning fitted him to live in an intellectual environment, he chose, while still young, to abandon the world for a life of solitude. The region of Mount Sanai was then celebrated for the holiness of the monks who inhabited it; he betook himself thither and trained himself to the practice of the Christian virtues under the direction of a monk named Martyrius. After the death of Martyrius, John, wishing to practise greater mortifications, withdrew to a hermitage at the foot of the mountain. In this isolation he lived for some twenty years, constantly studying the lives of the saints and thus becoming one of the most learned doctors of the Church.

Now, about the book. The 1492 edition is an Italian translation of a Latin version that was translated from Greek. On the title page, it's not quite clear whether "Climacho" is part of the title, or part of the author's name. ("Climacho" is from the Latin climax, in its original Greek-derived meaning of "ladder.") It reads: Sancto Iouanni Climacho altrimenti Scala Paradisi. ("San Giovanni Climacho, or, Scala Paradisi.")

That's clarified at the beginning of the text. Roughly translating from the passage pictured below: "This sacred book has two names. One of its names is Tavola spirituale [Spiritual Table]. . . . The other is La santa scala [The Holy Ladder]. . . . And from this name 'Scala' the saint who wrote it is called San Giovanni Climaco, that is, San Giovanni della Scala, since 'Climax' in Greek and Latin means 'Scala' [in Italian].")

![Scala Paradisi (Venice, 1492), page [3] (detail) Scala Paradisi (Venice, 1492), page [3] (detail)](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/johnclimacus1492-2.jpg)

What is The Holy Ladder or The Ladder of Paradise? (Some other titles it's known by are The Ladder of Divine Ascent and The Spiritual Tables.) You could call it one of the first self-help books ever written. It's a step-by-step guide—literally—to achieving spiritual perfection. It is divided into thirty "gradi" or steps. As the New Catholic Encyclopedia describes it:

. . . The ascetic life is portrayed in the form of a ladder that the monk must ascend, each step on the ladder representing a virtue that must be acquired or a vice that must be eradicated. There are 30 steps. . . . Each step is the subject of a chapter in which the author describes the virtue or vice in question and shows the way in which it is to be acquired or eliminated.

That has "best-seller" written all over it, doesn't it? And indeed the Ladder has been a popular work for many centuries for both monastic and lay readers, as witnessed by no fewer than three incunabula editions in the Italian language, suggesting a target audience outside monastery walls. In a Spanish translation, it is believed to be the first book printed in the New World, but unfortunately no copies are known to have survived. (See Carver in "Resources," below.)

We are all ascetics now, all practicing social distancing—not only from each other, from friends and strangers and loved ones alike, but from most of the things of the physical world we once thought essential to our being. It is hard to make peace with this, necessary as it is just now. Perhaps some of the lessons of the Ladder of Paradise could be applicable to our fraught lives today. I'm going to quote a passage from a commentary by a modern German writer, Hugo Ball.

But now to the book itself. Not only the theologians, the philosophers too once knew that outside of asceticism a truly meaningful life is not possible. To have spirit means to maintain a distance from existence. Asceticism gave instruction on the laws of this distance. . . .

For the Neoplatonists . . . philosophy and asceticism are nearly identical. But the archetypes of ascetic philosophy are the Therapeutae or monks who in the words of Isidore of Pelusium "sit in the peace of the Lord's philosophy." What does this mean? It means that the perils of matter are known, that the impulses of the body are perceived to be illusionary paths to nothingness. . . .

In such an age the Spiritual Tables came into being: an assemblage of laws without which, according to contemporary opinion, an honest and sublime thought could not even be conceived.

In John Climacus this view is so strongly expressed that it allows a glimpse of the oldest tendency of the Therapeutae, that of exorcism. For him, asceticism is more than a requirement for pure thoughts, it is a requirement and a guarantee of spiritual health. Health, however, is the true, the paradisiacal nature of man, the state to which all yearn to return. Health is the casting off of all impediments and burdens of the soul. The superlative of health is immortality. Not by nature is humanity corrupt, but from habit. Not from nature do men lie, but from perversion. A life with or without God has paradise or death as a consequence.

(Ball, "Joannes Klimax," 21–23. See Resources, below. My translation.)

Ascetic in form as well as content, the Spencer edition of the Ladder of Paradise is illustrated only with two small woodcuts, and only one is new to the work. On the title page (see above) is a cut interpreted as the saint amid his disciples.

On page 4 is a Pietà, used previously in an unrelated work. It was perhaps chosen for this work because of the ladders in the background, which would have been needed to remove the body of Christ from the cross:

![From the copy in the Biblioteca Corsiniana, Rome, page [4] From the copy in the Biblioteca Corsiniana, Rome, page [4]](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/johnclimacus1492-4-rome-copyenhanced.jpg)

Neither of these portrays the "ladder of Paradise" as John conceived it. But the theme has fired artists' imaginations through the ages. Most celebrated is this icon at Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, where John composed his treatise:

Not everyone makes it all the way to the end of these self-help books without falling off the program!

Resources:

For those of you looking to achieve spiritual perfection from the comfort of your home: the 1492 edition of Scala Paradisi is available in a digital edition from the Biblioteca Corsina in Rome.

But if your archaic Italian is a little rusty, the Library has other resources, available from home, that you may wish to consult. Below are a few. For several, you will need a valid New York Public Library library card, which is free and available to every New York State resident. If you don't have one, virtual signup is possible via NYPL's E-Reader app, SimplyE.

In the list below, the first link is to the catalog record; the second gives direct access to the resource.

Note: online access for some of these resources has been expanded during the COVID-19 crisis (they are normally available in our physical locations only).

1. On John Climacus:

- Clugnet, Léon. "John Climacus, Saint." In The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. Free access via HathiTrust (not NYPL's copy); text transcription available on New Advent website.

- Downey, G. "John Climacus, St." In New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. Vol. 7. Detroit, MI: Gale, 2003. Access via Gale eBooks with a valid NYPL library card.

2. Three scholarly studies, and a monograph:

- Duffy, John. "Embellishing the Steps: Elements of Presentation and Style in 'The Heavenly Ladder' of John Climacus." In Dumbarton Oaks Papers 53 (1999): 1–17. Access via JSTOR with a valid NYPL library card.

- Torrance, Alexis C. "Repentance in the Oeuvre of St John of the Ladder." Chap. 7 in Repentance in Late Antiquity: Eastern Asceticism and the Framing of the Christian Life c.400-650 CE. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. Access via Oxford Scholarship Online with a valid NYPL library card.

- Zecher, Jonathan L. "The Angelic Life in Desert and Ladder: John Climacus's Re-Formulation of Ascetic Spirituality." In Journal of Early Christian Studies 21, no. 1 (2013): 111–36. Access via Proquest Research Library with a valid NYPL library card. Access via Project MUSE (free access during the COVID-19 crisis).

- Zecher, Jonathan L. The Role of Death in the Ladder of Divine Ascent and the Greek Ascetic Tradition. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2015. Access via Oxford Scholarship Online with a valid NYPL library card.

3. Critical edition of the Italian text of Scala Paradisi:

- John, Climacus, Saint. La Scala del Paradiso di S. Giovanni Climaco: testo di lingua. Corretto su antichi codici mss. per Antonio Ceruti. Bologna: G. Romagnoli, 1874. With modernized orthography; based on manuscript sources. Free access via HathiTrust.

4. A German-language study:

- Ball, Hugo. "Joannes Klimax." In Byzantinisches Christentum: Drei Heiligenleben, 1–60. München: Duncker & Humblot, 1923. By a noted Dadaist, from his post-Dada years. Free access via Google Books (not NYPL's copy).

(Excursus: a work more typical of how Ball is usually remembered:)

- Ball, Hugo. "Karawane." In Dada Almanach, 53. Berlin: E. Reiss, 1920. Free access via International Dada Archive (not NYPL's copy).

5. The Ladder of Paradise: the first work printed in the Americas?

- Carver, Alexander B. "Esteban Martín, the First Printer in the Western Hemisphere: An Examination of Documents and Opinion." In The Library Quarterly 39, no. 4 (1969): 344–52. Access via JSTOR with a valid NYPL library card.

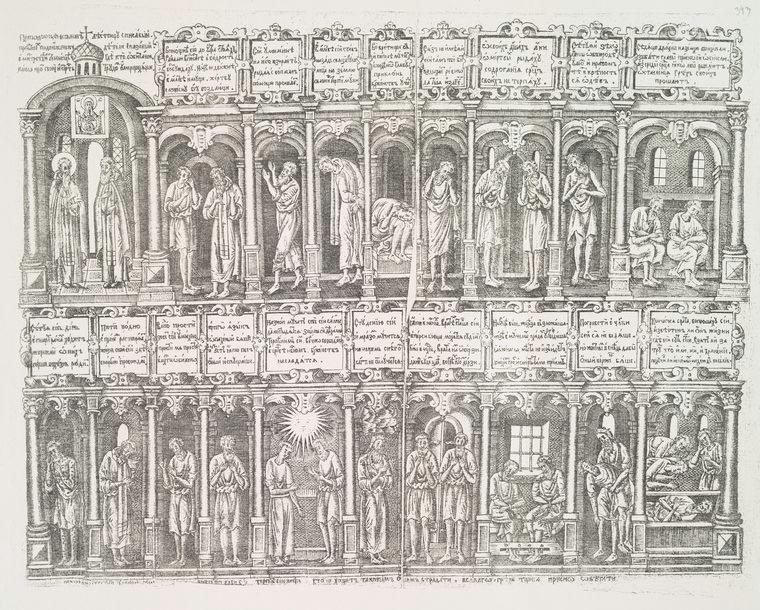

6. A horizontal Ladder:

- "Lestnitsa Ioanna Lestvichnika" ["The Ladder of John Climacus"]. Illustration in Rovinskiĭ, D. A., collector. Materīaly dl︠i︡a russkoĭ ikonografīi [Materials for Russian Iconography]. S.-Peterburg: Ėkspedi︠t︡sī︠i︡a Zagotovlenī︠i︡a Gosudarstvennykh Bumag, 1884-1890. Free access via NYPL's Digital Collections.

7. A musical setting of an excerpt from the Ladder:

- Primosch, James. "The Ladder of Divine Ascent." Disc 2, track 13 in Vocalisms: Songs of Crozier, Harbison, Primosch, Rorem, 2018. Part of the song cycle Holy the Firm (1999); the English translation is by Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell, adapted by the composer. Performers: Mary Mackenzie, soprano; Heidi Louise Williams, piano. Access via Naxos Music Library with a valid NYPL library card (return to the link after you have logged in, and it will take you to the album). Naxos also has the booklet, containing the text.

8. Not related to the work by John Climacus, but sharing its title:

- A Little Pamphlet Entituled the Ladder of Paradise. London: Imprinted for Edward Aggas, 1580? This is another work titled Scala Paradisi (also known as Scala Claustralium, or The Ladder of Monks). It is now usually attributed to Guigo II, a twelfth-century general of the Carthusian order, but was formerly thought to be by Saint Augustine himself. Access via Early English Books Online with a valid NYPL library card.

9. Also not really related to John Climacus, but a fun fact: The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard published a few works under the pseudonyms Johannes Climacus and Anti-Climacus. NYPL has "Philosophical Crumbs" and its "Concluding Unscientific Postscript," "Practice in Christianity," and "The Sickness unto Death" in the original Danish:

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Philosophiske smuler, eller, En smule philosophi. Af Johannes Climacus, udgivet af S. Kierkegaard. 2. udgave. Kjøbenhavn: C. A. Reitzel, 1865. Free access via HathiTrust.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Afsluttende uvidenskabelig efterskrift til de Philosophiske smuler: Mimisk-pathetisk-dialektisk sammenskrift, existentielt indlæg. Af Johannes Climacus, udgiven af S. Kierkegaard. 2. udgave. Kjøbenhavn: C. A. Reitzel, 1874. Free access via HathiTrust (not NYPL's copy).

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Indøvelse i christendom. Af Anti-Climacus, udgivet af S. Kierkegaard. 3. udgave. Kjøbenhavn: C. A. Reitzel, 1863. Free access via HathiTrust.

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Sygdommen til døden: en christelig psychologisk udvikling til opbyggelse og opvækkelse. Af Anti-Climacus, udgivet af S. Kierkegaard. 2. udgave. Kjøbenhavn: C. A. Reitzel, 1865. Free access via HathiTrust (not NYPL's copy)

The "Concluding Unscientific Postscript" in English:

- Kierkegaard, Søren. Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992. Access via Project MUSE (free access during the COVID-19 crisis).

10. And finally, a scholarly article connecting Kierkegaard with the man from whom he borrowed his pseudonym:

- Johnson, Christopher D. L. "'The Silent Tone of the Eternal': Søren Kierkegaard and John Climacus on Silence." In Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 19, no. 2 (2019): 199–216. Access via Project MUSE (free access during the COVID-19 crisis).

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

The Ladder of Paradise

Submitted by Jim Martin (not verified) on May 12, 2020 - 7:34pm

Re: Is the text of The Ladder of Paradise available in English?

Submitted by Kathie Coblentz (not verified) on May 14, 2020 - 1:25am

I accessed the Lazarus Moore

Submitted by Jim Martrin (not verified) on May 17, 2020 - 1:49pm

Rest in peace, Kathy Coblentz

Submitted by Peter Verdirame (not verified) on June 4, 2021 - 10:28am

critical edition of the Greek text of the Ladder

Submitted by Maxim Venetskov (not verified) on July 16, 2021 - 6:08am