Stories from the U.S. Federal Census

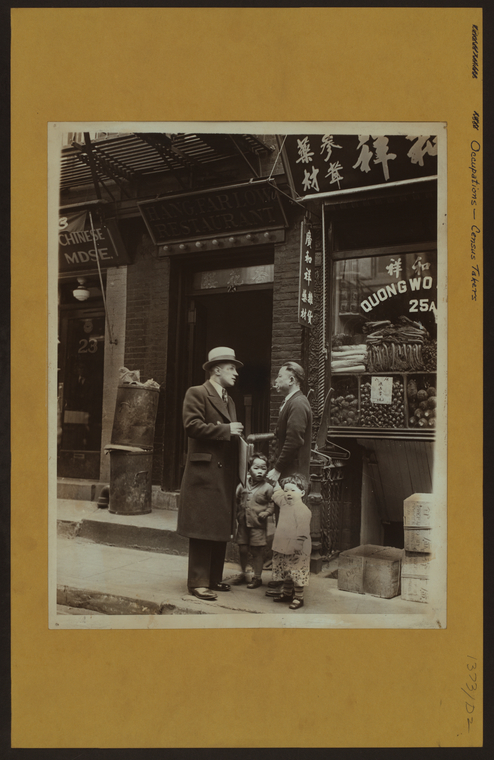

The 2020 Census marks the 24th time that the United States has counted its population since 1790. The following article explores the history and research uses of the census, comparing population and slave schedules with published and unique items from collections at the New York Public Library that describe the history of the Federal census, and the people it records.

Many of the collections referred to are availble free online, or with a NYPL library card (details at the end). This post features contributions from Philip Sutton and Andy McCarthy, reference librarians in the Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy; Miguel A. Rosales, Reference Librarian, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, and Julie Golia, Curator of History, Social Sciences, and Government Information, NYPL.

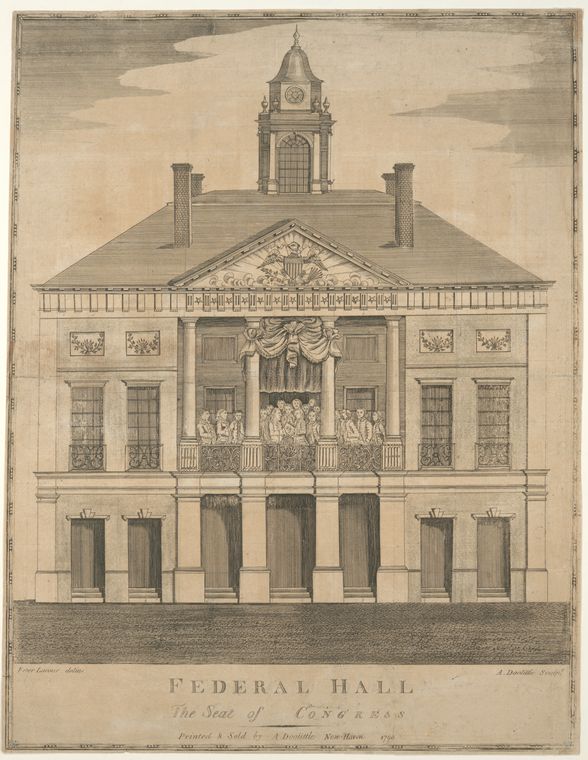

1790: The First Census

When Congress, in December 1784, resolved to hold future sessions in New York, the old City Hall was offered for use. The building was remodeled and renamed Federal Hall. On March 1, 1790, it was here that the first Census Act was passed. Congress assigned responsibility for collecting the 1790 census to the marshals of the U.S. judicial districts under an act which, with minor modifications and extensions, governed census taking through 1840.

The first census of the United States was taken beginning August 2, 1790. Mandated by Article 1, Section 2 of the Constitution, the census recorded the population of the United States, and was completed March 1st, 1792. The census was taken to apportion Representatives and taxes, and to determine the country’s industrial and military capability.

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.

The law required that every household be visited, that completed census schedules be posted in "two of the most public places within [each jurisdiction], there to remain for the inspection of all concerned..." and that "the aggregate amount of each description of persons" for every district be transmitted to the President.

The six inquiries in 1790 called for the name of the head of the family and the number of persons in each household of the following descriptions:

- Free White males of 16 years and upward

- Free White males under 16 years

- Free White females

- All other free persons

- Slaves

Under the general direction of Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State, marshals took the census in the original 13 States, plus the districts of Kentucky, Maine, and Vermont, and the Southwest Territory (Tennessee).

Enumerating the 1790 census employed an estimated 650 census enumerators at a cost of $44,000, and was completed March 1st 1792. When everything was tallied, Virginia was the most populous state (747,610), and Delaware the least (59,094). The resident population of the United States was recorded as 3,929,214. Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson expressed skepticism over the final count, expecting a number that exceeded the final tally.

The 1790 census tallied 33,131 residents in New York City; most of the population dwelled south of “Fresh Water Pond” (today the location just below Canal and Centre Street). In 2017, this section of Lower Manhattan was populated by 133,184 New Yorkers, according to the NYC Population Factfinder, an online data tool that employs census totals in conjunction with digital maps of the five boroughs.

1800-1840: John Jea

At the turn of the nineteenth century, slavery was legal in most northern states—but it was on the decline. By 1840, slavery had largely been abolished in the North. In the ensuing decades, activists, slave owners, and ordinary people battled over and negotiated the meaning of freedom, in ways we can sometimes see in data from the U.S. Census.

Emancipation came to the North in several ways. Most states enacted gradual emancipation laws. New York, for example, passed its gradual manumission law in 1799, promising freedom to those born after the law’s passage—but only when they reached adulthood. Some enslaved people were able to buy their own freedom. In other cases, slave owners chose to manumit their slaves, often in their wills. As a result, a growing number of African Americans born in bondage lived the last part of their lives free.

During this age of gradual emancipation, the Census served as a key record of data about slavery in the North. It indicated whether a head of household owned slaves or not, and it recorded the number of enslaved people in each household. Census data demonstrates that the coming of freedom in the North was not a simple process, nor a foregone conclusion.

After gaining freedom, many African Americans wrote about their experiences during enslavement. One such person was John Jea, who became a preacher after he gained his freedom in 1789. Born in Nigeria in 1773, Jea was kidnapped at the age of two, sold into slavery, and eventually purchased by Albert and Anetje Terhune of Kings County, New York. In his memoir, The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher, 1811, Jea described the horrors of life on their Flatlands farm—long work days, regular beatings, and inadequate food. It is unclear why the Terhunes freed Jea in 1789, but the family continued to own slaves for many years after.

By the mid-nineteenth century, old Dutch families like the Terhunes had amassed significant amounts of land in rural Kings County. As new transportation technologies made once-remote places like Flatlands more accessible, these families began to sell land to developers. An auction map of the Terhune property, situated in the towns of Gravesend & Flatlands, Kings County, surveyed & drawn by Martin G. Johnson, Jamaica, Sept. 1852 advertised the Terhune’s “valuable property” to potential buyers.

The Terhunes were one of the oldest Dutch families in Kings County. Relatives traced their ancestry back to Albert Albertse Terhune, who arrived in New Amsterdam in 1654 and procured farmland in the remote area of Flatlands on the western end of Long Island. Like most early Dutch families in Kings County, the Terhunes were prolific slave owners. Today, dozens of streets and places in Brooklyn bear the names of these families: Lefferts, Bergen, Cortelyou, Remsen, and many more.

Flatlands, Kings, New York, p.624, Albert Terhune.

Family History Library Film: 19371

In his autobiography, John Jea names his enslavers as Oliver and Angelika Triehuen, but no record of anyone by that name has been located. Based on family data, historian Graham Hodges has concluded that his owners were likely Albert and Anetje Terhune, Dutch Americans with deep roots in Flatlands. Albert and Anetje Terhune freed John Jea in 1789. But eleven years later, the family still enslaved people on their Flatlands farm.

1840: Solomon Northrup

Columns in the 1840 census enumerate the free household of Solomon Northrup, author of Twelve Years a Slave, and his family living in Saratoga Springs, New York. Other than the head of household, no family members are named in the 1840 census, and instead are identified by age and sex.

The following year, Solomon was abducted by slave traders posing as traveling circus performers, and later sold to farmer Edwin Epps in Louisiana. Traces of Solomon’s identity while enslaved can be found in 1850 census records, where family relationships are not explicitly stated and must be inferred using surnames and corroborating data.

The 1850 slave schedule—which enumerated the age, race, and sex of enslaved household members but did not list their names, only the name of the slaveowner—records eight enslaved individuals in the Epps household, including one 40-year-old male, almost certainly Solomon Northrup.

![1850 U.S. census, Louisiana slave schedule, Parish of Avoyelles, Edwin Epps [slaveholder]. Ancestry Library Edition. 1850 U.S. census, Louisiana slave schedule, Parish of Avoyelles, Edwin Epps [slaveholder]. Ancestry Library Edition.](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/1850_us_slave_schedule_edwin_epps_2_1.jpg)

Meanwhile, in 1850 Solomon’s family lived free in Saratoga Springs, NY. The census enumerates Northrup’s wife Anne living with her daughter Elizabeth, 19, and Rosanne Swift, 34, the property’s owner. Next door is the household of Solomon and Anne’s daughter, Margaret, and son-in-law, Philip Stanton, who have a one-year-old son poignantly named after his grandfather.

Five years later New York conducted the 1855 New York state census. It records Solomon Northrup, age 49, back living as a free individual with his family in Queensbury, Warren County, and sharing an address with the family of Phillip and Margaret Stanton and his grandchildren.

1850: William Wilson of Seneca Village

William Wilson, born c. 1811, was the sexton of All Angel’s Episcopal Church, in Seneca Village, the 19th century African-American settlement destroyed to make way for Central Park in New York City. Wilson is listed in the 1850 U.S. census as “mulatto,” age 39, living with his wife Charlotte, 28, and children, William, 13, Josh, 10, John, 8, Isiah, 6, Charlotte, 3, and a newborn infant, Jason. Wilson is recorded as owning real estate valued at $600, and his occupation is given as laborer.

The New York State census of 1855 also records Wilson as a property owner, and the Wilson’s home as being a frame building. That Wilson owned property qualified him to vote. Census evidence refutes the New-York Daily Tribune’s May 28, 1856 assertion that Seneca Village was a “squatter sovereignty,” a myth that persisted for years, as evidenced on p.329 of the 1916 edition of Rider's New York City guidebook.

![] Plan for the improvement of the Central Park, adopted by the Commissioners, June 3rd, 1856.](https://images.nypl.org/index.php?id=1697276&t=w)

Egbert Viele’s map of 1856 shows where Seneca Village was located, to the North of the Receiving Reservoir (shown in the top map), between 79th and 86th streets.

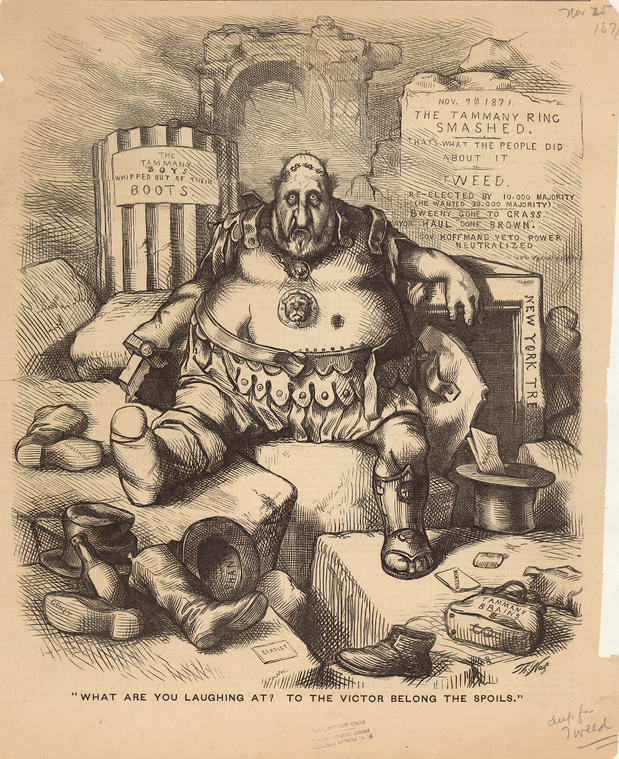

1870: Boss Tweed

William Magear Tweed (1823-1878), sometimes referred to as William Marcy tweed, the infamous Boss Tweed, was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for New York's 5th district, Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall, the powerful Democrat political machine that dominated New York City politics in the 19th century, a Member of the New York Senate, and Deputy Street Commissioner for New York City. In 1877 it was estimated that during his time in NYC government he stole between $25 and $45 million from the city’s taxpayers.

![552509 [detail] 552509 [detail]](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/tweed_1870_clip.jpg)

Tweed’s census entry for 1870 lists him living with his wife, Mary, and children: Mary, Josephine, Richard, Jenny, Charles, and George Tweed. No information is given about the family’s ages, or the value of Tweed’s real and personal estate. The census taker wrote:

Many fruitless attempts have been made to ascertain other data concerning [the] family of Wm. M. Tweed and returns are now forwarded.

According to the census, Tweed shares his home with 8 servants, 3 more than Cornelius Vanderbilt. Investigations into corruption led to his arrest in 1871. He died in Ludlow Prison in 1878.

1890: The End of the Frontier

The results of the 1890 federal census indicated that the survey of the western United States was complete. "Four centuries from the discovery of America," wrote historian Frederick Jackson Turner, "the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history." Late 19th and early 20th century brochures, from the Milstein Division’s collections of tourist ephemera, show how these frontier territories were soon promoted for tourism and development.

- Tourists’ Hand-Book of Colorado, New Mexico and Utah Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, 1887

- Dude Ranches in the Big Horn Mountains. Burlington Route, 1925.

Incidentally, the 1890 federal census population schedule was damaged in a 1921 fire, and after a consensus between the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of the Census and the Librarian of Congress in 1933, Congress authorized its disposal; only records in a few counties in a few U.S. states survive.

1900: Life on Cherry Street, NYC

Photographic views of New York City, 1870's-1970's, from the collections of the New York Public Library. Comprises some approximately 54,000 photographs, including images of buildings and neighborhood scenes, arranged by borough and street. The below photograph includes 408 Cherry Street, a six story, Old Law Tenement building built in the 1880s, and photographed in 1937. The 1900 census records the names and vital statistics of the people who lived there.

The 1900 census records the names and vital statistics of the people who lived there. The 1900 Census enumerates 113 people living at 408, 47 of whom, mostly children, were born in New York. Other residents had immigrated to the United States, overwhelmingly from Russia, mostly in the 1890s. Occupations described include baker, carpenter, shirtmaker, grocer, shoemaker, tinsmith, day laborer, servant, and teamster.

![Atlas of the city of New York, Borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley. 1902 [detail] Atlas of the city of New York, Borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley. 1902 [detail]](https://live-cdn-www.nypl.org/s3fs-public/cherry_map_1902.jpg)

Plate 14 of G.W. Bromley’s Land book of the borough of Manhattan, city of New York (1899, amended to 1902) shows 408 Cherry Street, seen in the photograph of 1937, whose occupants appear in the census of 1900. It is part of Block 261, between Scammel and Jackson.

Photographs of the interiors of tenement buildings taken in the 1930s suggest what the interiors of tenement buildings, such as 408 Cherry Street, may have looked like in the 1900s, providing clues to the lives and living conditions of the people described in census records.

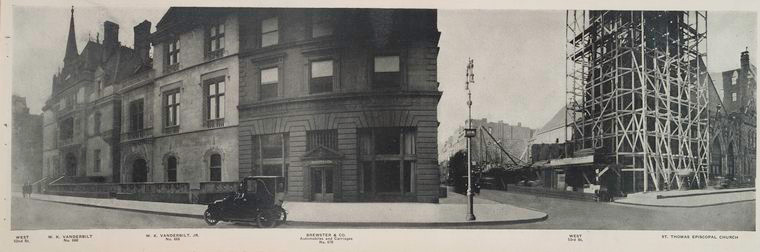

1910: The Gilded Age

Created by Burton Welles, in 1911, the Fifth Avenue from Start to Finish collection comprises wide-angle photographs of every building on Fifth Avenue, and includes the newly built New York Public Library, the Flatiron Building, Madison Square Park, the Metropolitan Life Tower, Saint Patrick's Cathedral, the Waldorf-Astoria, the Lenox Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Windsor Arcade. Also included are the homes of the rich and famous Cornelius Vanderbilt, S.R. Guggenheim, Charles W. Morse, Andrew Carnegie, William Roosevelt, John Jacob Astor, and the Havemeyers. Seen below, to the right of the picture, is 660 Fifth Avenue, the home of William K. Vanderbilt.

The 1910 Census below describes members of the Vanderbilt family at 660 and 666 Fifth Avenue. At 660 lives William K. Vanderbilt, 60, the son of William Henry Vanderbilt (1821–1885), eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1877-1794). William lives with his second wife, Annie Vanderbilt, 49, and her children [Samuel] Steven[s] Sands, 27, Margaret Rutherford, 18, and her sister Barbara, 14. The census states that the Vanderbilt household includes four servants, maids, Sarah Auld, born Canada, immigrated 1889, Christina Jenkins, 29, born Scotland, immigrated 1904, and Matilda Mitchell, 24, born Ireland, immigrated 1909, and “houseman” Enrico Baretto, 28, born Italy, immigrated 1909.

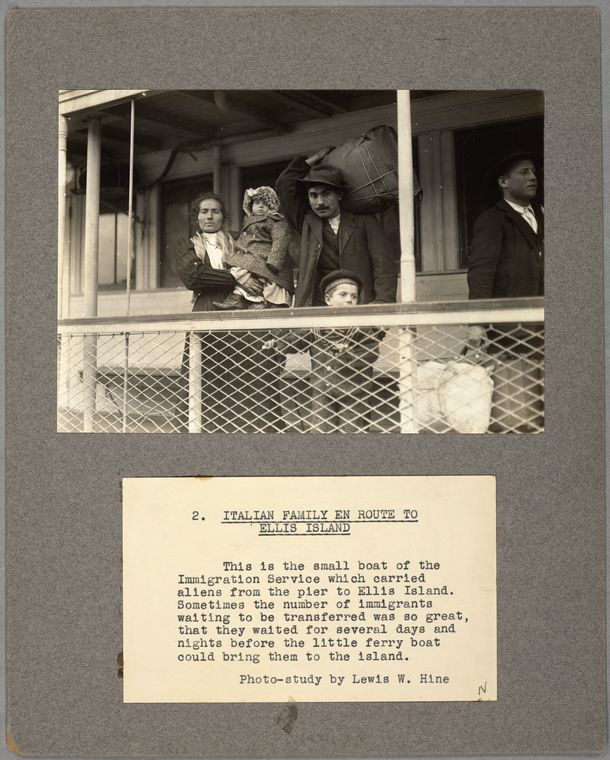

Lewis Wickes Hines’ 1905 photograph Italian Family En Route to Ellis Island captures Italian immigrants arriving at Ellis Island via ferryboat from the steamship that likely brought them to the United States. Records show that William Vanderbilt’s houseman, Enrico Baretto actually arrived at the Port of New York in 1906—the census can sometimes be wrong—and was likely also processed through the immigration receiving station at Ellis island.

1930: Technology Recorded

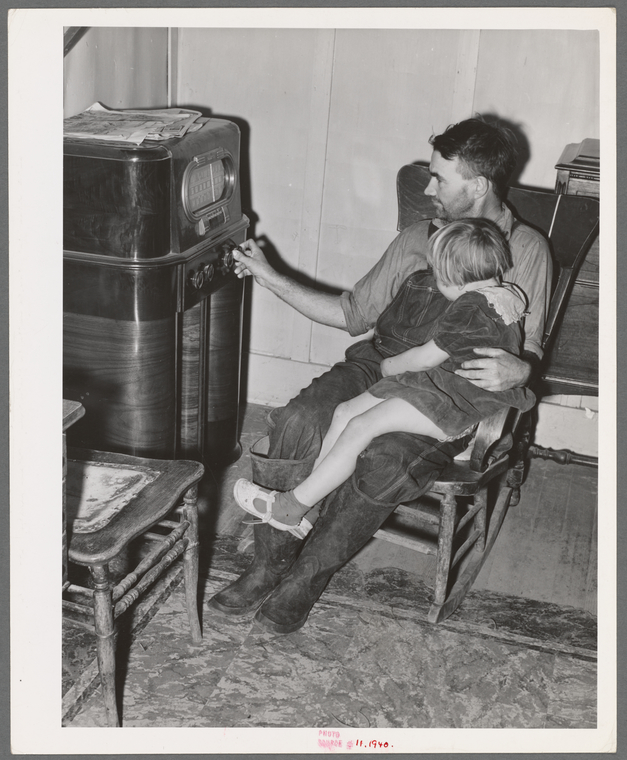

Information recorded in censuses often provides clues to technological developments. For instance, after the daguerreotype was introduced worldwide in 1839, censuses by 1850 list the occupation “daguerreotypist.” With the advent of cinema in the late 19th century, the census in the 20th century records the occupation of “cinematographer.” In October 1920, Westinghouse in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania became the first US commercial broadcasting station to be licensed when it was granted call letters KDKA. The 1930 census then asked if households had a radio.

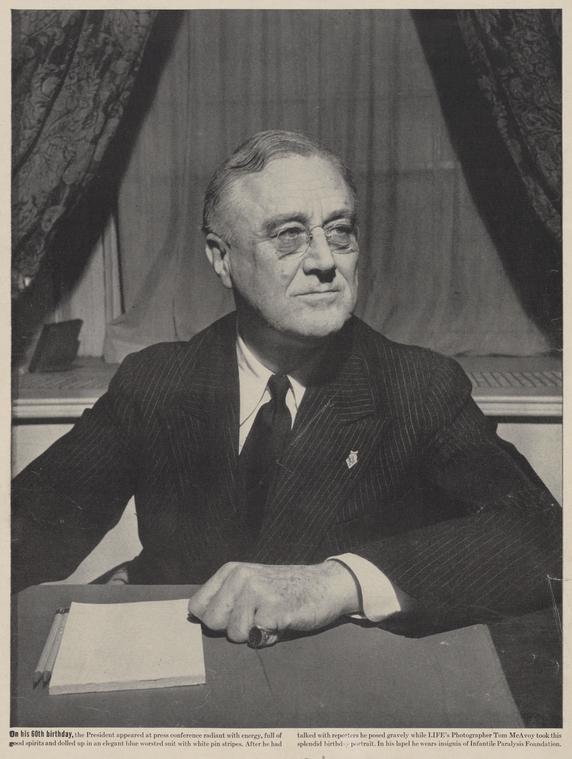

According to the 1930 census, the household of Franklin D. Roosevelt, then Governor of New York State, is listed as being in possession of a radio—denoted by the letter "R" in the eight column from the left. F.D.R. made the first of his famous fireside chats while Governor of New York, April 3, 1929, on Schenectady’s WGY Radio. He began making informal radio addresses to the nation as President on March 12, 1933, eight days after his inauguration, and made his last broadcast Monday, June 12, 1944.

1940: The Great Depression

Whereas the censuses of 1900 through 1930 concerned themselves with gathering information about, amongst other things, immigration and citizenship, as well as infant mortality, and radio ownership, the census of 1940 stands as a record of the economic devastation wrought by the Great Depression of the 1930s, and President Roosevelt's subsequent New Deal recovery program.

The 1940 census included questions about internal migration; employment status; participation in the New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Works Progress Administration (WPA), and National Youth Administration (NYA) programs. The 1940 census records the Fessler family, Samuel P. Fessler, 56, born Pennsylvania, a farmer, his wife Susan D. Fessler, 48, born Missouri, and their son, Sam C. Fessler, 16, born New Mexico. They live in Marion, Missouri. To capture data about economic migration, essentially how many Americans were moving around the country looking for work, the 1940 census asked the enumerated where they had been living five years previously. In 1935 the Fessler’s were living in Mills, New Mexico

In 1935 Dorothea Lange took the photograph "The town of Mills, New Mexico. The grain elevator in background at right has been long ago abandoned. The bank is closed". The image is, like many of Lange’s photographs of the time, very evocative, a visual record of economic decline and struggle, of a town and it’s people. Earlier censuses show that the Fessler family had been in Mills, New Mexico, for about 20 years. Why they left Mills, we can only surmise, but the census records that it happened, and the photograph shows that economic hardship was present in that place.

A selection of online sources used for this post:

- Ancestry Library Edition (with NYPL / Simply-E card)

- NYPL Digital Collections

- United States Census Bureau: History Much of the data used in this post comes from the U.S. Census Bureau.

- Family Search

- Hathi Trust

- The Internet Archive

See How to Access the Library's Digital Resources 24/7 for more information about accessing Ancestry Library Edition and other digital resources from home.

Note:

In the original version of this blog post, it was stated that Alexander Hamilton was living in New York City at the time of the 1790 census. He was, in fact, living with Benj. Rush at 79 Water St. Philadelphia. The Census record is hard to make out, but you can just make out "Alex. Hamilton Secretary of the Treasury of the U.S." Thanks to Douglas Hamilton for alerting us to this information.

Alexander Hamilton.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Alexander Hamilton census informatiom

Submitted by Douglas Hamiton (not verified) on October 25, 2020 - 11:20am

Your image of the 1790 U.S. Census

Submitted by Douglas Hamilton (not verified) on December 10, 2020 - 8:20am

Alexander Hamilton census information

Submitted by Philip Sutton on December 10, 2020 - 12:10pm