Africa and the African Diaspora

Catherine Latimer: The New York Public Library's First Black Librarian

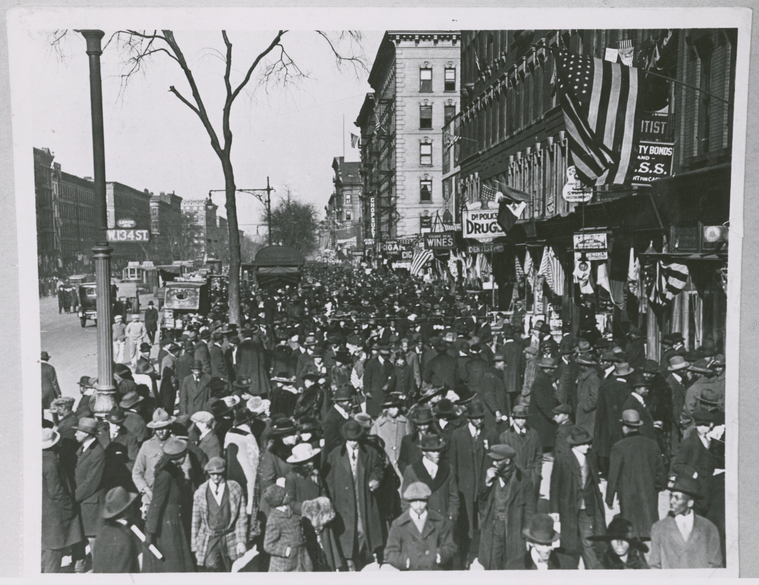

Black New York: In 1625, eleven enslaved Africans arrived in New Amsterdam to physically clear the land for what we now know as New York City. Some parts of New York, such as Harlem, are well-known black neighborhoods, but black people have lived in and impacted all parts of New York City for centuries. Let us take some time to explore the many areas of New York City where African Americans have lived and thrived. For this segment we are heading to Harlem, circa 1920…

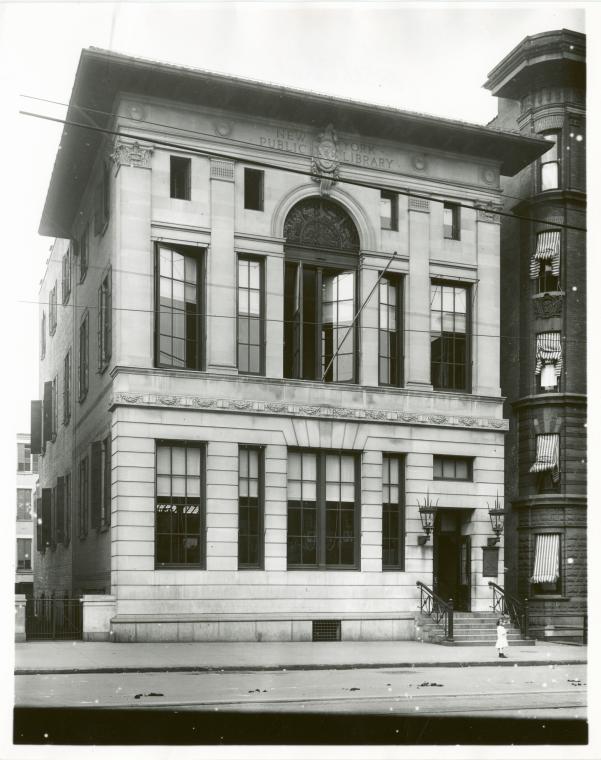

On a beautiful September morning in 1921, the young poet, Langston Hughes, exited the subway at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem. In 1921 Harlem was fast becoming a burgeoning mecca for black artists, writers, and performers. After making a few stops, Langston found his way to the Harlem Branch Library where, as he described, a “warm and wonderful librarian, Miss Ernestine Rose, white, made newcomers feel welcome, as did her assistant in charge of the Schomburg Collection*, Catherine Latimer, a luscious cafe au lait.” Although, only in the position one year when Langston Hughes made his observations, Catherine Latimer would go on to play a significant role in the history of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and The New York Public Library as, among other things, NYPL’s first African American librarian.

Not For Everyone—Public Libraries in the Early 20th Century

When we look back on the fight against segregation, the discussion often leads to the integration of schools; of public establishments such as restaurants and shopping areas; and public transportation. Libraries are often a side-note of the fight for equal access to public spaces. In her book, Not Free, Not for All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow , Cheryl Knott explains that, “Americans tend to imagine their public libraries as time-honored advocates of equitable access to information for all. Through much of the twentieth century, however, many black Americans were denied access to public libraries or allowed admittance only to separate and smaller buildings and collections.” Similar to the previous post in the Black New York series, where black nurses just out of nursing school were not allowed to treat white patients, black librarians had a similar experience, severely limited in what type of patronage they could serve and institutions they could be a part of.

Black New York

In the very beginning of the 20th century, ca. 1900, around 10,000 black people lived in San Juan Hill, a neighborhood in New York City which covered the area of 40th Street to about 65th Street on the West Side of Manhattan. However, during the early stages of the Great Migration, according to Cheryl Knott, in just one decade, between “1919 and 1920, the black population of New York City increased from 91,709 to 152,467.” The migration was not just happening externally, the black population was moving within New York City. Around 1905 Harlem was a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. A 1925 article in the African American newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier, specifically described the shifting demographic of the neighborhood by looking at the patronage of the local New York Public Library branch. “In 1905, [n]inety-five per cent (sic) of the library patrons were white. In 1920 the percentage had changed to fifty-fifty. Three years later 90 percent of the readers were Negroes, and today 95 per cent.” This change did not go unnoticed at the 135th Street Branch by the head librarian, Ernestine Rose.

Shifting Demographics and the Call for Black Librarians at the New York Public Library

Catherine Allen Latimer: The Early Years

The Schomburg Years

This issue was quickly picked up by the press and sensationalized, with one headline reading, "Harlem Group on Warpath for Scalp of 135th St. Library Head". As evidenced by letters between Latimer and Du Bois there was some tension at the 135th street branch between Rose, Latimer and Schomburg. After the article came out in the newspaper, Schomburg approached Latimer to explain that he had nothing to do with its publication. Another article was published soon after, with input by Du Bois explaining that he and the other advocates were not after Schomburg but fighting for the rights of the black employees at NYPL. With the continued advocacy of Du Bois and and a later grant by the Carnegie Foundation, Latimer was not demoted and Schomburg was made Curator of the Negro Division, while Latimer remained as its Reference Librarian. According to letters written by Latimer, she and Schomburg appeared to mend whatever tension existed between them, but she never completely trusted Ernestine Rose again, she wrote to DuBois in 1932:

NYPL, the Later Years

- As described by scholar, Dr. Laura Helton, Latimer, “built on a tradition of countercataloging at black institutions”, by re-cataloging items about the African diaspora in a way that was actually accessible to researchers. For example, she “removed books on Africa from the class for travel...and moved them to ethnology or history.”

- Started clipping files on dozens of topics covering the black experience and later turned those clipping files into scrapbooks. Librarians at the Schomburg Center carried on this tradition far past the time of Latimer, and these scrapbooks are heavily used by researchers today.

- Collected the works of great writers of the Harlem Renaissance that she knew personally, such as Claude McKay and Langston Hughes.

- Oversaw The Division of Negro Literature and History, which included the Schomburg Collection and promoted its special materials to reseachers, including a 1934 article published in The Crisis called, “Where Can I get Material on the Negro.”

- Worked with numerous researchers, and was especially helpful to researchers who were uncovering lesser-known historical moments from black history, for example Pearly Graham who was the first to uncover the relationship between Sally Hemmings and Thomas Jefferson.

- More recently discovered (and currently being researched by Dr. Laura Helton), Latimer created a black poetry index with her fellow librarian, Dorothy Porter from Howard University.

*It is important to note that although Langston Hughes refers to the collection at the 135th Street Branch as the Schomburg Collection, Arturo Schomburg’s collection was not acquired until 1925 and it was at that time that people often referred to it as the Schomburg Collection. The collection did not officially take on Mr. Schomburg’s name until 1940 and the Library was re-named after him in 1972.

References

American Library Association, Negro Library Service (Chicago: American Library

Association, 1925), 15.

"City Mourns Mrs. Latimer". (1948, September 25). New York Amsterdam News, p. 10.

"Death Claims Mrs. Latimer, The Librarian". (1948, September 18). New York Amsterdam News, p. 2.

Grossman, J.R (1989). Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989, 3–4.

"Harlem Group on Warpath for Scalp of 135th St. Library Head. (1932, January 23). Afro-American, p. 7.

"Harlem Library Fight Not Against Schomberg, But to Save Employees". (1932, January 30). Afro-American, p. 7.

Helton, L. E. (2019). "On Decimals, Catalogs, and Racial Imaginaries of Reading." Pmla, 134(1), 99–120. doi: 10.1632/pmla.2019.134.1.99

Hughes, L. (1963). "My Early Days in Harlem". Freedom Ways, 3(Summer), 312–14.

Jardins, J. D. (2006). "Black Librarians and the Search for Womens Biography during the New Negro History Movement". OAH Magazine of History, 20(1), 15–18. doi: 10.1093/maghis/20.1.15

Latimer, C. A. (1934). "Where Can I Get Material on the Negro." The Crisis, 41(June), 164–165.

"Mrs. Latimer in Charge of Negro History Department". (1927, January 26). The New York Amsterdam News, p. 9.

Knott, C. (2015). Not free, Not For All: Public Libraries in the Age of Jim Crow. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Sink, B. (2015, October 27). Catherine Bosley Allen Latimer (1896-1948)

Sink, B. (2015, September 15). "The Struggles of NYPL’s Pioneering African-American Librarians"

Walton, L. A. (1925, August 15). "Library Is Barometer of Race's Growth In N.Y." The Pittsburgh Courier.

“Work with Negroes Round Table,” Papers and Proceedings of the Forty-Fourth Annual

Meeting of the American Library Association (Chicago: American Library Association,

1922), 362–66.

More in the Black New York Series

- The Howard Colored Orphan Asylum: New York’s First Black-Run Orphanage

- San Juan Hill and the Black Nurses of the Stillman Settlement

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Catherine Latimer

Submitted by Ethelene Whitmire (not verified) on March 24, 2020 - 7:56pm

Catherine Latimer article

Submitted by Diana Lachatanere (not verified) on April 29, 2020 - 6:20pm

Thank you. What a gift and

Submitted by constance j str... (not verified) on June 11, 2020 - 11:35pm

Interesting reading about the

Submitted by Thomas Berry (not verified) on February 19, 2022 - 9:09am