Geography Lessons by Amanda Vaill

The following post was written by author Amanda Vaill, whose books include the bestselling Everybody Was So Young: Gerald and Sara Murphy, A Lost Generation Love Story; Somewhere: The Life of Jerome Robbins; Hotel Florida: Truth, Love, and Death in the Spanish Civil War, and the forthcoming The World Opened Up: Selected Writings of Jerome Robbins.

She is also the author of the Emmy-nominated screenplay for the Emmy- and Peabody Award-winning documentary, Jerome Robbins: Something to Dance About, and her journalism and criticism have appeared in numerous periodicals, from The American Scholar and Architectural Digest to Travel & Leisure and The Washington Post. A finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle Award, a 1999 Guggenheim Fellow, and a 2017 Fellow of the Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University, Vaill is currently a Fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library, where she’s at work on a biography of the Schuyler sisters, wife and sister-in-law of Alexander Hamilton.

-------------------

"Doing a ballet," Jerome Robbins told an interviewer in 1982, "is like knowing that there is an island out there that you want to explore but you don’t quite know the shape of it, or the details of it, or the dimensions of it, or the geography, or what you’ll find on it. And only by approaching it and getting closer and closer does it begin to define itself… Until then, it’s like going toward it a little bit in the mist and not being sure of what it will be like until you get there." If this description is true of Robbins’ creative process, it’s also true of his life—as I first discovered when doing research for my 2006 biography, Somewhere: The Life of Jerome Robbins, and have learned all over again in assembling The World Opened Up: Selected Writings of Jerome Robbins, which will be published in 2019.

When I began the biography, I knew the rough outlines of Robbins' story: his childhood as the son of striving immigrant parents; his conflicted relationship with his Jewish heritage; his artistic apprenticeship in the Borscht Belt, on Broadway, and in Ballet Theatre; his explosion into stardom in 1944, at the age of 25, with the twin successes of Fancy Free and On the Town; his controversial appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee during the 1950’s; his complicated but reverential relationship with George Balanchine, who made him Associate Artistic Director of New York City Ballet when he was only thirty; his extraordinary, even revolutionary, career on both Broadway and in the ballet, which continued until his death in 1998, bare months before his 80th birthday. But I didn’t yet know the shape, or the details, or the geography, of his life.

On my first day in the as-yet-unprocessed Robbins archives, which were then still contained in filing cabinets in his 81st Street townhouse, I was looking for a toe-hold, a place to begin exploring. Knowing that Robbins and Leonard Bernstein, his then-unknown collaborator on the 1944 Fancy Free, had been separated by the demands of their professional lives during the creation of that work, and that—as both Robbins and Bernstein had said—they had carried on their creative dialogue via letters and recordings of the score, I thought this might be a good place to begin, with documents that would bring alive Robbins’, and Bernstein’s, emergence as mature artists.

So I asked Christopher Pennington, who had assisted Robbins and would become executive director of the Robbins Foundation and the Robbins Rights Trust, where the Fancy Free documents were filed. The answer filled me with dismay: "We’ve never found them," he told me. "We assume they’re lost."

Disappointed but resigned, I set myself a different entry point, and began going through the Robbins papers, file by file, transcribing and making notes. For a man who dealt in the kinetic and visual, Robbins was a surprisingly prolific and varied writer and, in addition to correspondence from a Who’s Who of 20th century culture, I discovered a huge trove of his own letters, journals, essays, memoirs, even fiction, all adding unexpected dimensions to my understanding of him.

Months, even years passed. The house was sold. The archives—and the Robbins office—moved to new quarters. I kept going through file drawers. One day, looking for a break, I paused in my labors, pointed to a huge movers’ carton in the corner of the office, and asked Chris Pennington, "What’s in there?" "Duplicate scripts of The Poppa Piece," he said, referring to an unproduced autobiographical theater piece Robbins had written in the 1980s and workshopped at Lincoln Center Theater in 1991. "I don’t know why we’re keeping them around."

Maybe it was boredom that made me do it. "Let me just take a peek in there," I said. The carton was the size of a washing machine. As Chris had said, it was filled with photocopied scripts, held together with elastic bands. I pulled out the top layer of scripts, then the next, then the next, all the way to the very bottom. And there lay a leather box crafted to look like a book, the kind of box people used to put important documents into. On the spine was a paper label bearing Robbins’ distinctive back-slanting handwriting. "Fancy Free," it said.

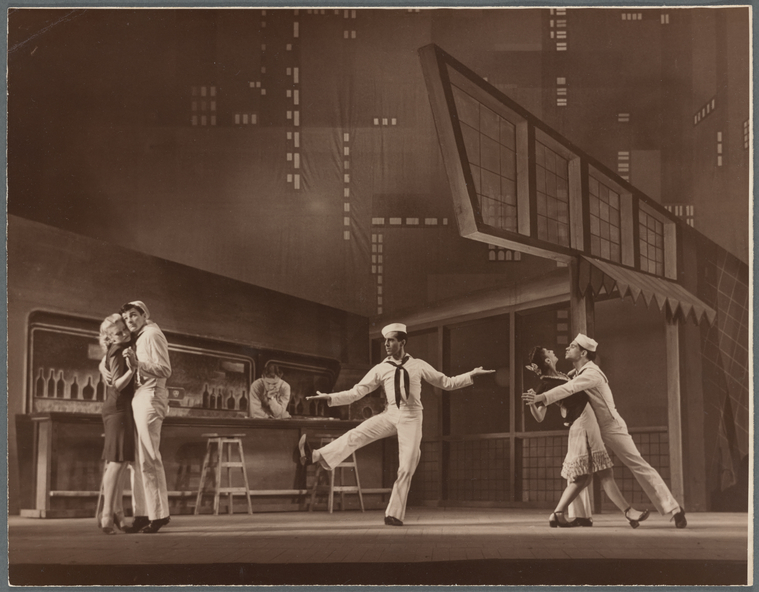

Inside the box were letters from Bernstein and Oliver Smith (Fancy Free’s designer), a little paper cut-out of the barroom set, and letters Robbins had sent to his collaborators—which they had seemingly returned to him—one of them illustrated with pen-and-ink sketches of the sailors in the ballet. The whole thing was like a time capsule containing the essence of who Robbins and his collaborators were at that moment in 1944, just before they became indelibly famous.

Apparently, knowing how important this material was to his own history, Robbins had sequestered it in the box, possibly intending to draw on it for the autobiography he contemplated but never completed. And now, quite by accident, I had found it. It was my first surprise, but not my last.

This past spring, as I completed the manuscript of my selection of Robbins writings, I came across something I never expected to find. I had arranged Robbins’ letters, diaries, memoirs, and critical and creative writing as a chronological narrative, a kind of autobiographical mosaic that would tell the story of his life as he had seen and experienced it. And there was one important episode that he had never spoken or written about in any detail—not in letters, not in his journals, not in his memoirs: his 1950 questioning by the FBI over his Communist associations in the 1940s, and his subsequent testimony as a "friendly witness" before HUAC, for which many people held him in contempt, or worse.

He had, however, written several versions of a surreal trial scene—in which his stand-in Jake Whitby, or Witkovitz, is brought to judgment for his political associations—for The Poppa Piece. So I’d decided to use that scene to stand for Robbins’ encounter with HUAC. Although I’d put one version of it into the manuscript, I thought I’d seen another in his papers that was more emotionally vivid and dramatic. In search of it, I went back to the Performing Arts Library and started reading through permutations and duplicates of the script. In among them I found an uncatalogued nine-page typed memorandum, dated 1950, that Robbins had prepared for his own files, a memorandum describing his grilling by the newspaper columnist and television host Ed Sullivan, and by the FBI, for whom Sullivan evidently acted as a kind of unofficial tipster.

Robbins must have written the memo for legal reasons, to set down the details of what had happened while they were fresh in his mind, in case he needed the information for his own protection; then, in the 1980s, when he was writing his dramatic version of those events, he’d used the memorandum to refresh his memory, and afterwards it had been mistakenly filed away, unlabeled. Now, from those forgotten pages, a frightened and confused young man spoke, and the geography of his life became a little clearer.

Shortly before this, another part of the island that is Jerome Robbins revealed itself. One of the great questions about Robbins, to those who worked with him or wrote about him, was what he thought of his own gifts. Perhaps because he frequently changed his mind about which way he was going with a work in progress, or (once the work was finished) was insistent that it be replicated exactly as he had set it, many people thought him insecure as an artist. And indeed, in his letters and journals, he was often doubtful about the quality of individual works—he complained to one correspondent about his dances for Call Me Madam, and to his diary about Glass Pieces, a ballet now widely considered a masterpiece. How, then, would he sum up his own career? The answer, like so many other elements of his story, was hidden in the mist.

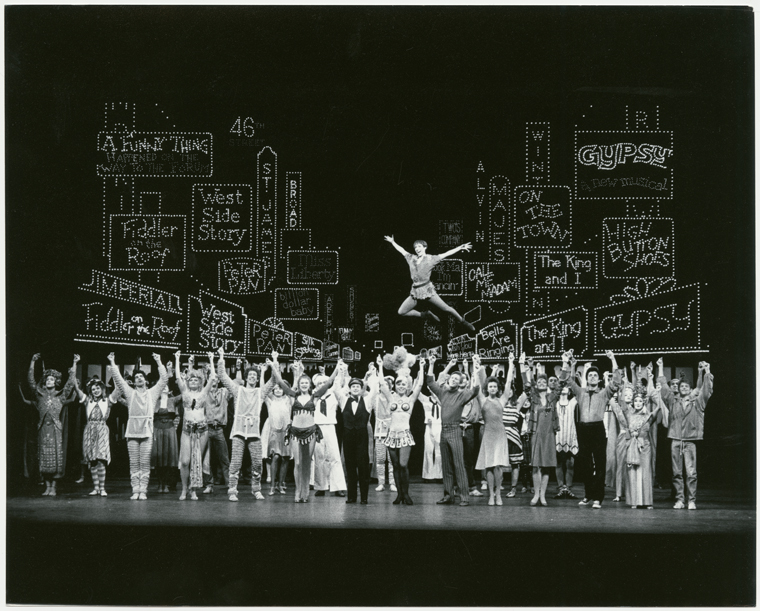

In 1989, Robbins directed his last Broadway show, an anthology of dance (and song) numbers from a career of musical hits that began with On the Town and ended with Fiddler On the Roof. Begun as an almost archival exercise, an effort to capture and record his revolutionary musical-theater output before it passed from memory, Jerome Robbins’ Broadway would become a Robbins hit on its own terms, winning six Tony Awards, including for direction and Best Musical.

But going into rehearsal, Robbins was anxious and depressed: "It will break me; either mind or body," he wrote in his journal. "I don’t want to do it – no fun, no joy, no help." One night, after supervising a preview performance, he came home to his townhouse on 81st Street and wrote himself a letter, on his "Jerome Robbins" stationery, in which he poured out his feelings about the show and about his own creative legacy. He put the letter in an envelope, addressed it to himself, sealed it, and put the envelope in between the pages of a souvenir program from the show. This program, in turn, found its way into a valise; the valise found its way into the basement of his house; and then, after Robbins’s death, a member of his household preserved the valise without looking at its contents. It wasn’t until a little more than a year ago that the valise was opened, the contents examined, and the letter discovered.

What’s written there, what Robbins had seemingly secreted away until an opportune time, was his last surprise. To find out what he said, you’ll have to wait until the publication of The World Opened Up; suffice it to say that it lifts the mist from the island and lets us see it clearly at last.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Amanda Vaill / Geography Lessons

Submitted by Beth Tondreau (not verified) on March 30, 2019 - 1:19pm