Finding Frederick Melton

In 1961, the photographer Frederick Melton turned over his archive of nearly 2,000 negatives to the New York Public Library’s Dance Division and set out for Puerto Rico, closing the book on his life in the New York City art world for good.

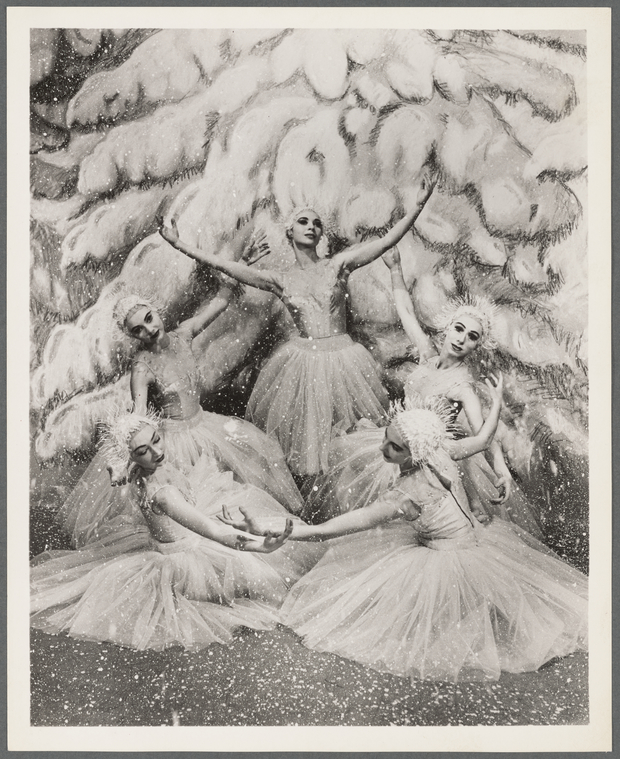

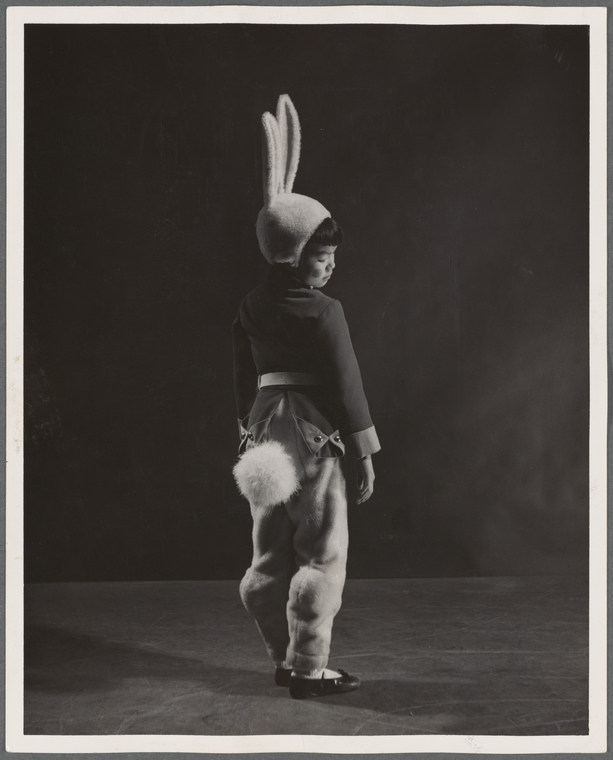

Almost 60 years later, Melton’s photographs of one of America's most beloved ballets formed the spine of the Library for the Performing Arts’s 2017-2018 holiday exhibition, Winter Wonderland: George Balanchine’s The Nutcracker®. Although other photographers (including Martha Swope, Zachary Freyman, and Radford Bascome) also documented the New York City Ballet’s original staging of The Nutcracker in 1954, more than half of the images on display were taken by Melton.

“Melton’s photographs of the original 1954 production of Balanchine’s The Nutcracker define and establish the tone of the ballet," explains Linda Murray, curator of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division and the exhibition.

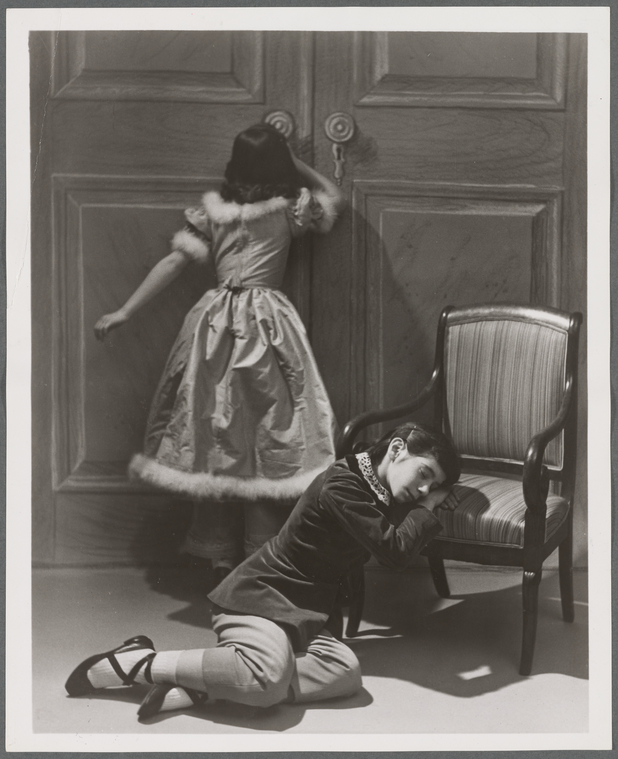

"While many view it as a confectionery work (the set of Act II is literally called Candy Land), as with all fairy tales there is a dark psychological terrain simmering beneath the surface," said Murray. "Balanchine wanted the ballet to expose the childhood experience of an adult environment where the reality of sizes and shapes is distorted (think of how the tree and mice dwarf Mary in their enormity) and where possibility is limited only by the boundaries of one's imagination."

"Playing with exposure and shadow, Melton’s photographs alternately immerse Mary in ornate crowded rooms with other children or isolate her in pools of light amidst a vast darkness," continued Murray. "His images make us aware that in witnessing the ballet we are seeing the world through her eyes and hers alone."

Melton's History

Photography was a sideline for Fred Melton, who dabbled in a number of creative media but was most successful during his New York years as a silk-screen printer. Born in Atlanta in 1918, Melton came to Manhattan in 1939 with his boyfriend, writer Donald Windham, and joined a social circle of mostly gay artists.

He rates mention in biographies of figures like W. H. Auden, Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes, and Tennessee Williams, who roomed with the couple for a time and co-wrote an early play with Windham. Later, in the late 1940s and '50s, Melton and a subsequent partner, Wilbur “Billy” Pippin, ran a printing press and an informal salon that served as a nexus for gay men in the arts, both of which were underwritten by Lincoln Kirstein.

It was through his connection to Kirstein and George Balanchine, co-founders of the New York City Ballet, that Melton was engaged to photograph many of the ballet’s early productions, including The Nutcracker.

The Search for a Rights Holder

To digitize Melton’s photographs and use them in our publicity for the exhibition, the Library was obliged to secure permission from the current copyright holder. After Melton left New York, there was little in the public record about him, other than a paid obituary in The New York Times (placed by his long-ago lover, Windham), which confirmed that Melton died in Fort Lauderdale in 1992.

It was my job to track down an estate. Because Melton’s brief death notice listed no survivors, I was concerned that I might not find one. Untangling the estates of gay and lesbian artists in the era prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage presents some unique challenges. Did Melton have a partner when he died? Even if I could find one, that partner would have inherited Melton's intellectual property only if Melton specified that in a will. If the actual heirs were relatives—siblings, nieces, nephews, cousins—they might prove impossible to locate, or perhaps ill-equipped or disinclined to administer an artist’s legacy.

Discovering a Life's Details

When I dug further, I found an intriguing footnote in a volume of Tennessee Williams’s correspondence, which mentioned that Melton had abruptly married around 1942. Was it possible that Melton had also had children?

A public records search revealed that Melton and his wife, Sarah “Sally” Marshall, did indeed have two sons in the mid 1940s. Although the eldest child was deceased, I eventually located Melton’s younger son, Christopher, an architect who was restoring the Macon, Georgia home in which he grew up.

Christopher filled me in on many of the details of his father’s life after New York City. Frederick Melton left for Puerto Rico in the 1960s because his health was failing. Although he was only in his early forties, he had circulation problems, consumed alcohol and tobacco to excess, and decided that he would “just drink himself to death on the beaches.” (Melton may also have fallen out with his New York social circle; he told Christopher that Lincoln Kirstein had “dropped him” without explanation, a slight that still hurt decades later.)

Instead of dying young as planned, Melton ended up having heart surgery in a Veterans Administration hospital, getting sober, and moving to Pompano Beach, Florida, where he opened a sign shop. In 1978, with his life newly stabilized, Melton reached out to the sons he’d seldom seen since they were small boys.

Melton had known his wife before he left Georgia, but they had begun their married life in the West Village, where Sally’s beloved boxer dog became just one source of many conflicts between Fred (not a dog enthusiast) and his young wife. Christopher and his brother were born in New York, but the family soon moved back to Sarah’s parents’ land in Macon.

Melton dove into small-town Southern life with gusto. He built a modern house and workshop on the property, painted, and worked on the newspaper and in the local theater. But the experiment in conformity didn’t last.

Early in 1948, Melton returned to New York—without his young family—and this time he stayed. "He was always this sort of mystical, magical character out there," said Christopher, who reminisced about how much he loved the imaginative gifts his father sent on birthdays and holidays. "They were always so terrific. I was really into pirates, and he sent me a real flintlock, not a copy. He sent me a real sword."

When I spoke with Christopher, I was curious about the circumstances surrounding his father’s excursion into straight marriage, which seemed like a departure from a life that was perhaps as openly gay as one could be in the middle of the twentieth century.

"We really never talked too much about this, but maybe in his early days he thought that he would end up being straight," Christopher says. “And my mother, being very beautiful and arrogant as well, thought that she would convince him that that was the best way to go." Melton’s sexuality may have been fluid, or appeared that way to others. His nickname among his male friends was Butch, and "he was pretty butch," laughs Christopher. “He rode a Harley and he was a tough little guy.”

A Final Family Reunion

When Melton wrote to his sons in 1978, Christopher’s brother "had no use for it, but I was curious." Christopher and his father became close during the latter’s final years, visiting each other in Colorado, where Christopher lived at the time, and in Florida. After Fred Melton died, his son became the keeper of his artistic legacy. As the executor of his father’s estate, Christopher (who visited Lincoln Center to see the exhibition) granted NYPL permission to display Melton’s work on our website.

Once an agreement with Melton's estate had been reached, Dance staff made digitizing the negatives a priority, and units of the Library's Digital Research began the work of scanning and describing Melton's archive. The entirety of the collection is now available to researchers via our Digital Collections website. If you're in a festive mood, you can spend some time perusing Frederick Melton's more than 500 images of the 1954 The Nutcracker.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Fred "Butch" Melton

Submitted by Susan Black (not verified) on September 3, 2021 - 5:53pm