Prisons, Property, and the American Revolution

Just as soon as they won the Revolution and secured their independence, Americans began incarcerating more people. In a society founded ostensibly on freedom or liberty, what could be a graver punishment than taking away one’s freedom? Interestingly, Americans after the country’s founding saw prisons as a progressive innovation in line with revolutionary values. They believed prisons were both a more humane and a more effective form of punishment. They replaced public corporal punishment and limited the number of crimes punishable by death, a transformation in focus toward rehabilitating people as opposed to exacting retribution from them.

The transformation of criminal punishment was particularly evident in the urban north—especially Philadelphia and New York City. Yet even by 1800, fewer than five percent of the United States’ five million people lived in cities of more than 10,000 people. The changing role of prisons was far less pronounced elsewhere, in rural areas like Albany County, as this post shows, using recently digitized materials from the Abraham Yates, Jr. papers, and the Theodorus Bailey Myers Collection from the Library’s archival collections.

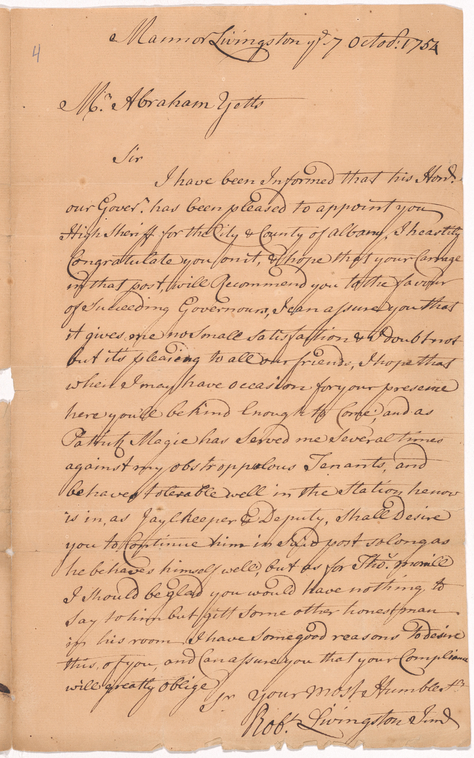

There was a new sheriff in town in 1754. Not long after Abraham Yates, Jr. took office as the high sheriff of Albany County, he started to hear from powerful men like Robert Livingston, Jr. Livingston and his family owned tens of thousands of acres—basically all of what is now Columbia County—though they did not work that land. Instead, these manor lords leased small plots to tenant farmers, often for their entire lives. Livingston first wrote Yates to congratulate him on his new appointment. Tellingly, Livingston also added that “Patrick Magie has served me several times against my obstropolous Tenants,” and requested Yates keep him “in the station he now is in, as jaylkeeper[sic].” Livingston’s main goal was to protect his vast landed empire. He needed to ensure that the institutions of government and justice served his interests.

Livingston had reason to expect he might need the jail-keeper, in particular, in his pocket. Tenants got a raw deal. Proprietors usually exercised a right of first refusal on their tenants’ crops; the tenant farmer could not sell to other parties until the landlord passed on buying them. Similarly, on many manors, tenants had to take their grain to their landlord’s mill for processing, which meant there was no competition and landlords could set prices. In addition to all of this, as part of their lease, most tenants still had to pay the property taxes on their piece of land even though they did not own it. Understandably, tenant frustrations boiled over into outright revolt on the Manors with some regularity.

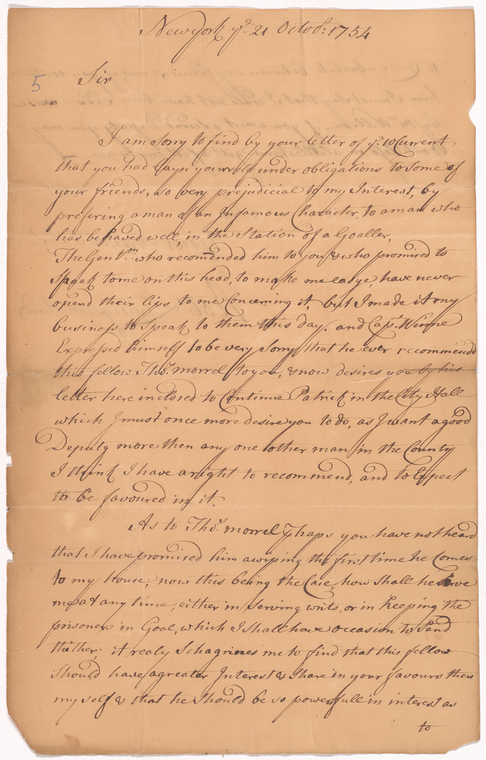

Livingston, then the Lord of the Manor, had a lot at stake in limiting these conflagrations. He took an interest in Yates because he wanted to ensure Yates would work with him to limit those. But Yates did not bow to the pressure of the powerful manor lord, opting to appoint a different man as his deputy and the jail-keeper. Livingston was enraged. He wrote Yates that he “was sorry to find” the sheriff “under obligations to some of your friends, so very prejudicial to my interest” to such a degree that he would make “a man of an infamous character” the jailkeeper.” It “schagrines[sic] me,” Livingston concluded, “to find that this fellow should have a greater interest & share in your favours than myself.”

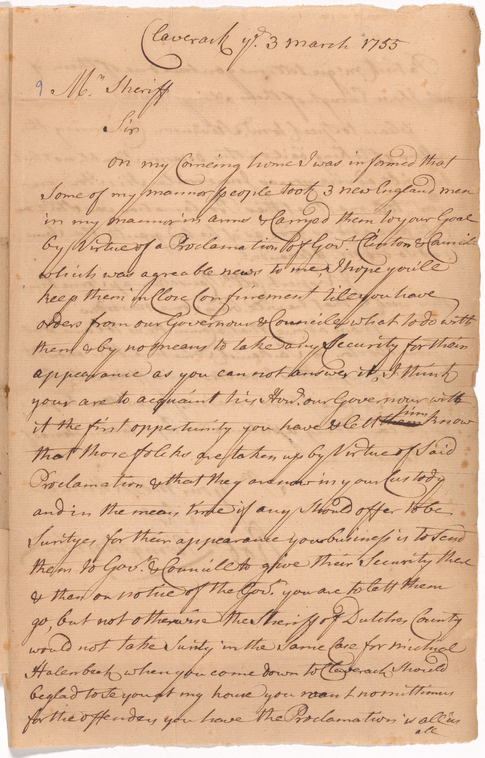

But Livingston still needed to work with Yates in order to protect his property holdings. So he cooled off. In 1755, when some of his “manor people” armed New Englanders streaming across the Berkshire Mountains, Livingston wrote Yates that “I hope you’ll keep them in close confinement.” Public corporal punishment only went so far; sometimes, Livingston simply needed troublemakers confined so that the turmoil would have time to abate. Yates did as asked and helped quell the riots. Even still, Livingston never totally got over Yates’ early independent streak. By the end of the 1750s, Yates was no longer sheriff. Livingston blocked his attempts to gain election to other offices. Livingston needed administration of justice to serve his interest absolutely.

Manors in the upper Hudson Valley survived the Revolution. The Livingstons and other families managed to maintain much of their pre-revolutionary landholdings. Yet all was not the same. The populace embraced the democratic ideals of the Revolution and grew increasingly assertive in politics.

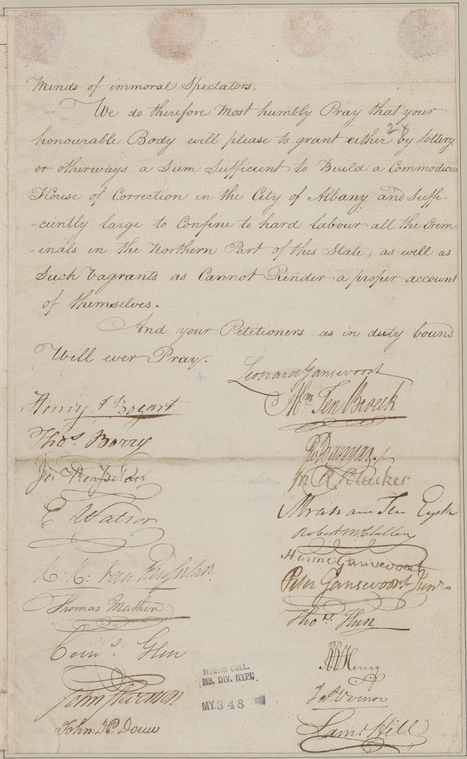

Oddly enough, one of the first things citizens complained to the Legislature about was the insecurity of their property. They sounded a bit like the manor lords. A broad swath of men from the northern reaches of New York—especially Albany—bemoaned that “Felons, Robbers and thieves have of late years Increased and are dayly[sic] Increasing in this Part of the State to an alarming degree. Inasmuch that your Petitioners are under constant apprehensions for the Safety of their Property and the Peace of orderly Citizens greatly disturbed.” They demanded the state do something to combat this.

In particular, the petitioners wanted a prison. Embracing the new revolutionary logic behind prisons, they claimed they were “fully convinced that the recent experience of several Countries in Europe as well as in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, to confine convicted Criminals to hard labour for life or a specific number of years according to the extent of their Crimes has had a most happy tendency by holding up its victims as Standing monuments of Guilt and remorse.” The state should raise money “sufficient to Build a Commodious House of Correction in the City of Albany and sufficiently large to confine to hard labour all the criminals in the northern Part of this state.” Despite the American Revolution, prisons continued to protect property owners and their social order from the have-nots.

Further Reading:

On changing conceptions of punishment and the rise of prisons in revolutionary America, see Jen Manion, Liberty’s Prisoners: Carceral Culture in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); and Michael Meranze, Laboratories of Virtue: Punishment, Revolution, and Authority in Philadelphia, 1760-1835 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996). On the manorial system and land riots in the Upper Hudson Valley, see Thomas J. Humphrey, Land and Liberty: Hudson Valley Riots in the Age of Revolution (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2004). Biographical information of many of the petitioners are available through “The People of Colonial Albany,” a database created by Stefan Bielinski as part of the Colonial Albany Social History project that he ran at the New York State Museum.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Great research If only

Submitted by Louise Stamp (not verified) on February 1, 2017 - 11:38am