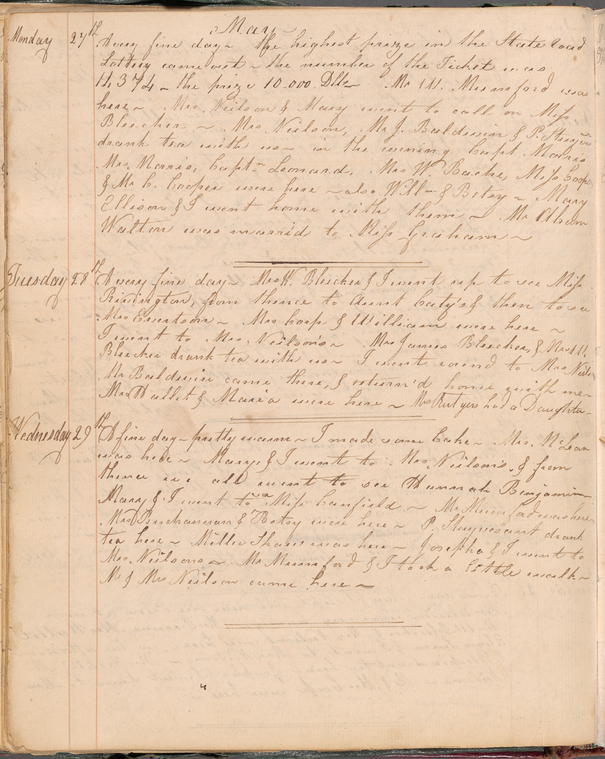

Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker Diary, May 27, 1799

“A very fine day- the highest prize in the state road lottery came out - the number of the ticket was 11,374 - the prize 10,000 Dolls…” Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker, May 27, 1799.

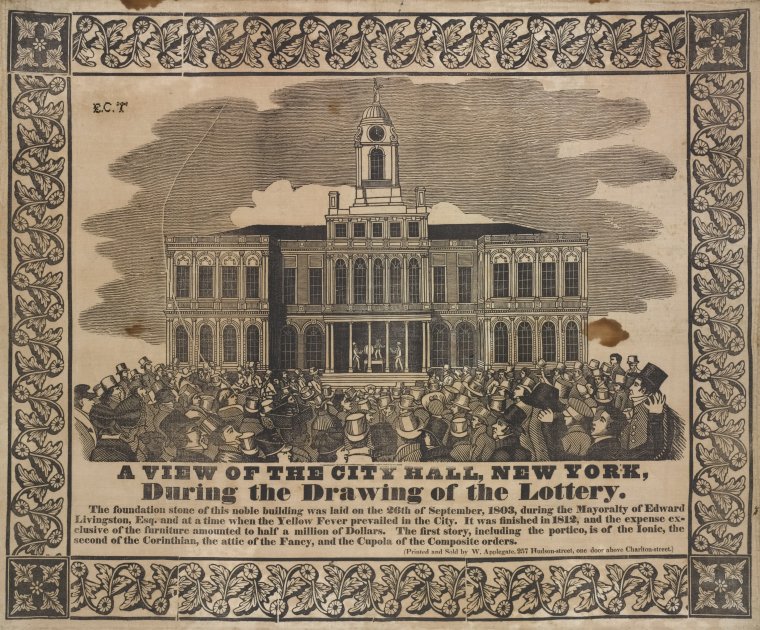

What immediately jumps out in this entry of Elizabeth Bleecker’s diary is the massive—for its time—prize. It must be why Bleecker took note. That evening, newspapers reported that “the fortunate possessors” of the $10,000 ticket “are a company of five gentlemen.” More generally, we know that New Yorkers were keenly interested in lottery drawings, which tended to stretch over a number of days, even weeks. The drawing for this 1799 lottery took place in Federal Hall (then City Hall), with the permission of the New York Common Council. What can get lost in the excitement of drawings and prizes is how lotteries served important public goals. As Bleecker noted, this was specifically a “road lottery,” a complex production that raised funds for a series of major public works projects in upstate and western New York.

The State Road Lottery

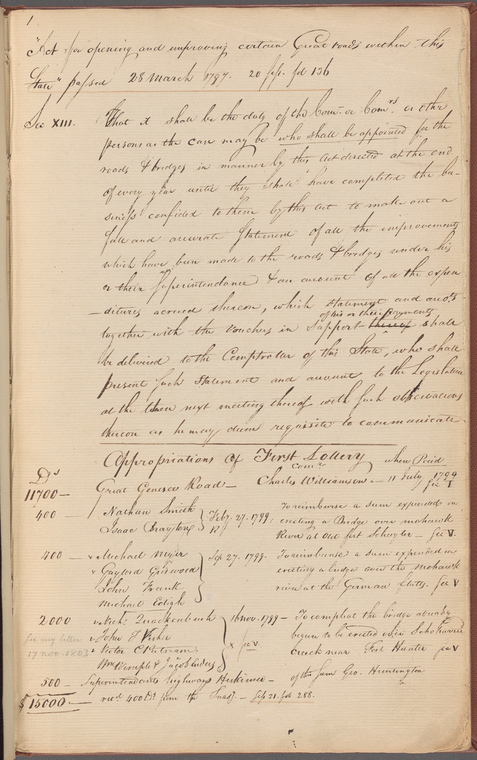

What Bleecker and most of her contemporaries called the “state road lottery” was a series of three lotteries, all authorized by a single law in 1797. The New York State Legislature passed “An Act for Opening and Improving certain Great Roads within this State” because they sensed that “it is highly necessary that direct communications be opened between the western, northern and southern parts of this state.” Over the next four years, lottery managers in Manhattan and Albany coordinated the sale of some 75,000 tickets at $5 apiece ($375,000 in total), in order to raise $45,000 for a series of infrastructure projects that would foster communication and exchange across the state.

Nearly half of the lottery proceeds funded two projects. Over $11,000 went to improve the Great Genesee Road—which ran from the Mohawk River in Herkimer County, to the Genesee River at Geneva, in Ontario County, then the westernmost county in the state. Another $11,000-plus was earmarked to service a road that stretched northward from Albany to Lake Champlain.

The New York State Comptroller—an office created in 1797, the very same year that the legislature approved the road lottery—oversaw the use of the funds. A “memorandum book” kept by various comptrollers between 1799 and 1826, which details transactions and contains reports related to many state projects, including those funded by the road lottery, was also recently digitized.

Early American Lotteries

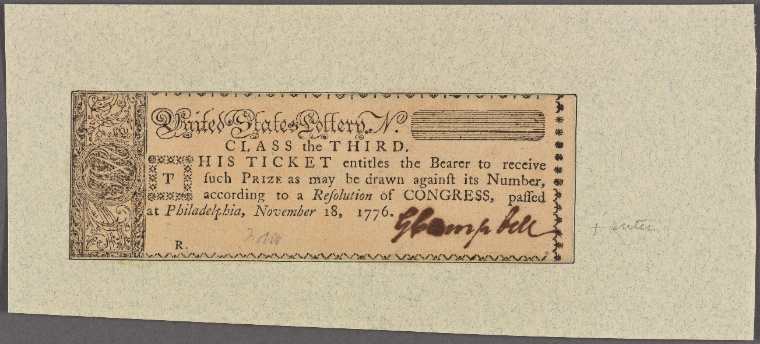

Lotteries were already a major part of early American life by the time New York authorized its state road lotteries. During the colonial period, many churches and schools used lotteries to raise necessary funds. Communities found them useful for maintaining roads, piers, and other communal infrastructure. Shortly after the United States declared its independence from Great Britain, in November of 1776, the Continental Congress authorized a lottery to raise money for the war effort. With cash in short supply, and the majority of tax dollars going to pay off the war debt, lotteries grew more popular after the American Revolution.

At the same time, lotteries made Americans anxious. In 1783, New York banned “private lotteries”--lotteries run without the state’s permission, sometimes as a business venture—because they were a “public nuisance” that “occasion idleness and dissipation, and have been productive of frauds.” Without supporting some public purpose, a lottery was simply another a form of gambling. And of course, the state had an interest in maintaining a monopoly on lotteries. Yet Americans had to grapple with the possibility that even the most publicly beneficial lotteries still had the same ill effects as any other form of gambling.

The problems were also civic. Lotteries may have benefitted projects that served the public good. Using them to fund public projects, though, absolved individuals of having to act in the interest of the common good. Remember, New Yorkers spent $375,000 on lottery tickets between 1797 and 1801, to raise just $45,000 to build roads that would surely benefit the state. We have to assume the legislature went through this cumbersome process instead of levying a tax because they figured the self-interested pursuit of easy riches was a more effective motivator than public spirit.

By the antebellum period, anxieties about lotteries boiled over. In 1821, New York adopted a new constitution, which banned lotteries. Most states either banned lotteries or stopped authorizing them around this time. By the Civil War, government-sanctioned lotteries had disappeared from nearly every state in the union. They only made a comeback a century later, though their rise since the 1960s has been meteoric.

*****

Lotteries were bound up in the broader challenge of funding governance and development in states in the early republic. Yet for Bleecker and many New Yorkers, the lottery may have been simply a public spectacle. It is hard to know what, if anything, Bleecker thought about lotteries or their increasingly important role in public finance. Perhaps that is the point, and a reminder of the value of historical manuscripts like Bleecker’s diary; it illustrates the mundane ways people experienced monumental transformations.

This is one of a series of monthly posts highlighting entries from the Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker Diary. Previous installments include a broad overview description of the diary, a post about labor in early New York and another about the election of 1800.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

digitazation of manuscript collection

Submitted by Jean Jones (not verified) on June 1, 2016 - 5:01pm