Black American Dance Narratives: A Survey of the Jerome Robbins Dance Division

All art is cultural expression, but none is more integrative than dance, which is made of our bodies—how we move, where we move, what we wear—to tell every story there is to tell of how we, humanity, live. This project is about black bodies that dance and, in doing so, tell a story that is about politics, sexuality, religion, economics, and mortality more than art. Dance is for the stage, but dance is also for life. This is a narrative outline based on research done at the New York Public Library on African and American contributions to culture and dance from the autobiographical point of view of a black female student/practitioner of dance in the twenty-first century.

Photographer unknown.

New York City is a mecca for anyone who takes the study and performance of dance seriously, especially if that person is Black. New York City represents many things in the world, it is also an African City—in the words of Robert Farris Thompson—the destination of blacks in search of an environment where their creative spirit can thrive. On any given day of the week you can do world dance, folkloric dance, black dance, to acoustic music in classes taught throughout the five boroughs in school gymnasia and studios small and big. Many of the classes, taught by master dancers from around the world, are attended by a mix of professionals and lay dancers who bring together an extraordinarily diverse group of people who form a local, national, and international community. Among the 25,000 moving image titles available for viewing in the Dance Division are several videos of classes from the 1990s at Fareta School of Dance and Drum.

Finding Community in Dance

Raised in the South, I migrated to New York to pursue literature, dance, and filmmaking as a career and lifestyle. I had been living in Atlanta for the last eleven years. I’d gone there to study at Clark College and Atlanta University, now joined as Clark Atlanta University. I also studied dance with Barbara Sullivan and became a member of the Apprentice Company of Barbara Sullivan’s Atlanta Dance Theater. The apprenticeship grew into a regular and full-time (if not lucrative) job—a pleasant surprise I never thought possible for myself.

Inasmuch as I loved dance, my upbringing never allowed that it could be something I’d ever do professionally or even publicly, though I would discover that some of my family, long before me, had. One of my Atlanta University Center friends was Leon King, who was a dancer in Sullivan’s Company (and would later join Dianne McIntyre’s Sounds of Motion company in New York City). He repeated, “You should dance” to me enough times that I got the nerve to attend classes. The studio happened to be across the street from my then apartment on Auburn Avenue; I had no more excuses. I walked into the studio one evening and basically didn’t leave—for long—for the next 5 years or so.

S. Hurok Presents Katherine Dunham as Queen in Rites of Passage.

Photographer unknown.

My first teacher in New York City was Lavinia Williams, who is well documented in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division, including twenty-one videos. Paulette Gary aka Yesembiat had turned me onto her Haitian class at STEPS on Broadway at that time and I remain grateful to her for it. This would be the only class I’d take in New York since I had decided—against my better judgment—to set dance aside to focus on a career-track job I’d gotten in book publishing. If I had to come to mecca and had to decide on just one teacher, she—contemporary of Katherine Dunham, mother of Sara Yarborough (with whom I’d taken ballet in Atlanta), a legend and beautiful spirit—was the one. The Jerome Robbins Dance Division has more than twenty videos of Sara Yarborough and over three hundred items on or about Katherine Dunham, over one hundred of these are videos, many directly from the collective title Katherine Dunham Centers Collection.

Photographer unknown.

In retrospect it should have occurred to me to seek out Eleo Pomare as a teacher given that Barbara Sullivan, my first significant teacher, had studied and performed with him. But, I’d long decided that I’d leave modern and ballet behind to focus on ethnic and/or folkloric African-based dance. I’d had gotten enough of a taste, learning what I did from Sullivan and seeing fantastic performers, including the Senegalese Ballet when they came to Georgia State University in the 1970s. The Dance Division has forty-seven videos of Eleo Pomare, including an early film from 1967, Blues for the Jungle, danced by members of the Eleo Pomare Dance Company: Chuck Davis, Michael Ebbin, Strody Meekins, Al Perryman, Eleo Pomare, Ron Pratt, Bernard Spriggs, Shawneequa B. Scott, Lillian Coleman, Judi Dearing, Carole Johnson, Jeannet R. Rollins, Shirley Rushing, and Dolores Vanison (call number: *MGZHB 16-833). There is also an audio recording of an oral history interview of Pomare by host Lucile Brahms Nathanson. Broadcast on the radio station of Nassau Community College, WHPC-FM, New York, on its series Making the Dance Scene. (call number: *MGZTC 3-408).

Photographer unknown.

in Blues for the Jungle,

Photograph by Leroy Henderson.

Photographer unknown.

The NYPL’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division has many audio/visual documents of dance companies of African nations, including a seven minute promotional video of The National Dance Company of Senegal (call number *MGZIA 4-2646). I found some twenty-seven video recordings of dance using the search keyword "dance—Senegal," including many from Brooklyn Academy of Music’s DanceAfrica series, Evidence Dance Company’s trip to Senegal (call number *MGZIDVD 5-6870); Dance in Africa: the first World Festival of Negro Arts produced by Gallery Amrad, filmed in performance in Dakar, Senegal, in April 1966. (call number *MGZIC 9-4395), and National Dance Company of Senegal from the 1980s (call number *MGZIA 4-1287).

As a parting gift, Atlanta-based mentors and friends had given me lists of names of places to find all of what I was looking for in the city. Dancewise, the Clark Center was at the top of the list. But, by the time I arrived in April 1984, the Clark Center was no more. Included in the many articles in the Dance Division’s catalog is a review entitled “Of Shouts and Stomps and Cultural Achievements: Clark Center Dance Festival," written by Jennifer Dunning for Dance magazine, (October 1976, pp. 33, 77-78, 80; call number *MGZA). The dancer/choreographer Charles Moore had a long association with the Clark Center. Included in the Dance Division’s archival collections is the 38-box collection of Clark Center papers documenting its activities from its founding by Alvin Ailey until its complete collapse in 1989 (Title: Clark Center records, 1960-1995, call number *MGZMD 176).

The Bathhouse aka the Hansborough Recreation Center on 135th Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenues was a popular place for African dance on Saturdays—Bernadine Jennings taught Congolese and, following her, other classes were taught by a number of teachers. Among the teachers were the Senegalese Jasmin, Amadou Boly Ndaiye, and Lamine Thiam who was introduced and coached in teaching by Amadou, and M’bemba Bangoura from Guinea. There are six videorecordings in the Dance Division documenting the work of Bangoura as a choreographer, composer, and instrumentalist, including one that also included the Dinizulu Dancers and Singers. Scores took both hour and a half long classes, happily dancing for three hours to the sound of beautiful percussive music and sometime the singing of such greats as Mor Seck, a brilliant traditional singer from Senegal and a Harlem resident.

The recent Dance Division African Dance Interview project has interviews with Lamine Thiam and others available online. The links for these are:

- Lamine Thiam interviewed by Carolyn Webb (*MGZIDF 1136), May 23, 2013.

- Maguette Camara interviewed by Ife Felix (*MGZIDF 4093), August 6, 2014.

- Mouminatou Camara interviewed by Malaika Adero (*MGZIDF 4095), August 27, 2014.

- Youssouf Koumbassa interviewed by Dionne Kamara (*MGZIDF 4096), August 28, 2014.

- N'Deye Gueye interviewed by Malaika Adero (*MGZIDF 4097), September 18, 2014.

These are now all available on the library website's Digital Collections page.

The Students

The class students included Butterfly McQueen, the actress known best for her unforgettable role in Gone with the Wind, the (would-be major bestselling) poet and novelist Sapphire, the actress and comic Phyliss Stickney, and jazz musician/band leader Cassandra Wilson. This class led me to others like it, sponsored by community organizations and taught by Esther Grant, Nafisa Sharrif, Wilhemina Taylor, and others. And then there were the classes offered by Forces of Nature Dance Company lead by Abdel Salaam and Dele Husbands, then held at the Synod House on the grounds of the Cathedral St. John the Divine. Esther Grant was teaching some of these classes as well. The Dance Division created a nearly six-hour oral history of Abdel Salaam in 1995, which can be listened to or the transcript read (call number *MGZMT 3-1870 [transcript] or *MGZTC 3-1870 [cassette]).

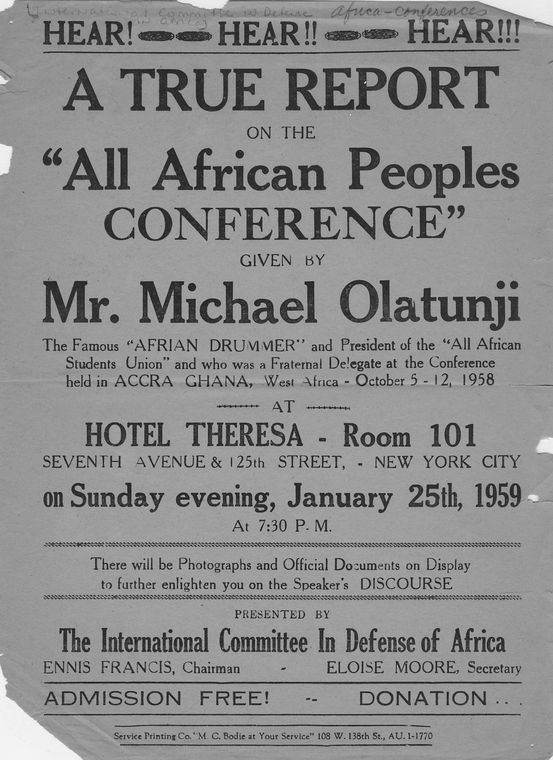

In this community, I befriended one dancer, Celeste “Aduke” Bullock, who introduced me to Baba Olatunji with whom I would study, work, and perform until his passing in 2003. One of the longest lived performing groups, when I came into the fold in 1991, the company was rising back up after a slump. New dancers were needed for the new phase, but there were dancers and musicians scattered all around the country who played with Drums of Passion over many years as circumstances allowed. Our most senior dancer during my tenure was Hasifa Rahman, Alalade Dreamer Frederick was dance captain, and there was “Bobo” Ben Sealy and Yak Tamale, Oyabunmi Rhoda Pfeiffer (mother of actor Mekhi Pfeiffer), Olabisi, Modupe Olatunji (daughter of Olatunji), Alesha Randolph, Myna Major, Deborah O’huru and many that I know and many I haven’t yet learned about.

If you studied dance, music, and culture under Olatunji and went on to perform with Drums of Passion you became a part of a family, a close community that transcended decades and geography. The group was a study in multiculturalism with performers coming from and living in regions across America, the Caribbean and Africa. Olatunji was a contemporary and acolyte of Kwame Nkrumah and his pan-Africanism was never more apparent nor consistent than in his dance company. The rank of the musicians was even more diverse, including as it did from time to time, non-black performers from all over the world.

Aduke Celeste Bullock became a mentee of Olatunji as a teenager. She published an essay describing her “personal feelings about taking African dance class” in Attitude: The Dancer’s Magazine [Summer/Fall 1991] p. 6; (African dance, call number *MGZA 93-327).

Drums of Passion, a recording by Babatunde Olatunji, released in 1959 or 1960, changed the game in black popular culture by reconnecting up with Africa. I was three years old in 1960 so I don’t remember a time before it was a part of our family collection. The album sold 5 million copies and became a part of our family collection by way of the Columbia Record Club. It operated like the Book of the Month Club where members received one item per month and four bonus titles when you signed up. Drums of Passion was one of the record club's bonuses, and that it was. I fell in love with the music and the images of the dancers on its cover. I don’t recall how long it took for me to actually see a Drums of Passion performance nor what television program I saw them on.

Michael Babatunde Olatunji arrived in the United States with his friend and cousin Akinsola Aiwowo in 1950, entering at the Port of New Orleans to reach Atlanta, Georgia, where he attended Morehouse College. He didn’t come to launch a career as a performer. He came to earn a degree and return home to be a leader in his community and nation. But he began performing informally on the campus of his college in part to dispel the myths his fellow American students held on to about Africa. Most Americans were tainted by stereotypic images in mass media, e.g., the Tarzan television series and many Saturday morning cartoons, and by our formal education, which reduced and maligned African culture to at best something primitive, exotic, and, at worst, depraved.

Baba considered returning to Africa from time to time, but lived out his life in the United States. He was, however, on faculty of the University of Ghana, in the dance department, and traveled there often from his base in America in addition to touring around the world—Europe, Canada, Latin America—to do workshops and performances for a wide range of audiences, from doctors at a convention in Italy to the New Age retreats across North America.

My initiation to the Babatunde Olatunji Drums of Passion family occurred at the start of the 1990s, but the seed was planted when I first heard the album Drums of Passion (1959). Michael Baba Olatunji was the headliner and band leader. I saw his original group on national television in the 1960s. The seed of African consciousness in Black Americans was watered by the influence of Olatunji’s music, fertilized by the black arts and consciousness movement that defined the times in America, and was in solidarity with the independence movement that swept across the continent of Africa.

More Drums of Passion, issued by Columbia Records in 1966 is in the Rogers and Hammerstein collection (R&H) at the Performing Arts Library. (call number * LZR 17035 [disc]).

Photographer unknown.

“The first American tour of Les Ballets Africains in February 1959 must have inspired Olatunji. So, too that troupe’s ‘superb’ (Martin 1959) jembe (djembe) drummer, Ladji Camara (1923-2004), who would move to the United Stated in the early 1960s, play with Dunham, and father a jembe movement in New York” (introduction by Eric Charry to The Beat of My Drum, 2004)

In its Original Documentation program in 1994, the Dance Division recorded Papa Ladji Camara, drumming and dancing (call number *MGZIC 9-4655). Performed by Les Ballets Africains de Papa Ladji Camara the drummers and singers include Papa Ladji Camara, Robert Palmer, James Cherry, Kehinde Donaldson, Vernon Brannon-Bey, Kevin Nathaniel Hylton, and Carolyn Webb.

Between 1991 and his passing in 2003, I was on the roster of dancers who performed and assisted the workshops in places, including at Esalen Institute in California; Hollyhock (Cortes Island, B.C.); Rhinebeck, New York, festivals and events across the United States and nearly in a half-dozen cities in Switzerland and other countries and places.

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has much in its collection on Olatunji, most in the Music Division. Folkloric performing arts and culture can’t be fully appreciated when broken up into separate categories and disciplines though. Olatunji insisted that the music, song, dance and dress be addressed and included in workshops and performance. The holistic approach is a question of authenticity, but also a question of potency and impact of what the witnesses or audience will experience in the presence of the art being practiced or performed. Likewise, a student, scholar, or writer whose subject is dance must gain knowledge and understanding of music, song, dress, and everything else that comes along with the dance experience of their focus.

In discussing this, Jerome Robbins Dance Division curator Jan Schmidt told me: “In the Performing Arts Library, the materials separated as subjects, are actually available in this wholistic approach in the one combined reading room. The music is heard at listening stations near the dance viewing stations, the photographs from all the divisions are requested in the same place and delivered to the same Special Collections area. Materials on Babatunde Olatunji include a wide range of formats including 4 print sources, 9 videorecordings, and 10 audioreocordings.”

Baba’s Early Years in the U.S.

Michael Henderson, a fellow alumnus of Babatunde Olatunji, or Baba (which means father), as many of us called him, described Baba in a release on the occasion of his passing in 2003: “Early career milestones [of Babatunde Olatunji] included performances at Radio City Music Hall, the 1964 New York World’s Fair, and TV appearances on programs like the Tonight Show, the Mike Douglas Show, and the Bell Telephone Hour. [He] has written many musical compositions, including scores for the Broadway and Hollywood productions of Raisin in the Sun."

Henderson further wrote “By the time Olatunji arrived in New York in 1954, [Asadata] Dafora, [Katherine] Dunham, and [Pearl] Primus had already developed an appreciation for staged African and Afro-Caribbean dance with African-based drumming accompaniment. Some of Olatunji’s drummers and dancers had worked with Dafora and Primus, and carried with them material and expertise, on which Olatunji built. For example, the Derby sisters, Merle ('Afuavi') and Joan ('Akwasiba'), contributed Fanga, which they learned from Primus" (Derby 1996).

Photograph by Barbara Morgan.

The Beat of My Drum: An Autobiography by Babatunde Olatunji with Robert Atkinson and a foreword by John Baez was published a couple of years after Olatunji's passing. Merle (aka Afuavi) Derby and her sister Akwasiba Derby were among the original Drums of Passion dancers, the latter becoming the dance captain and Baba’s right hand. She died young at age, but was elevated to legend by her contemporaries and the dancers who came after her. Her surviving sister, Merle Derby, was a quiet force who continued to dance late in her much longer life. She didn’t perform with Drums of Passion in the 1990s and later, but did consent to attend a rehearsal with the dancers who did, sharing what she remembered of choreography that remained a part of the repertoire and especially of dances—such as “World Without End”—that had been lost to the collective memory of the active group of performers. “Drumming It Up for Africa: Michael Babatunde Olatunji, the Drumming Virtuoso” is a piece she wrote for Tradition, a journal published out of Uniondale, New York (call number *MGZA 96-581 Tradition [Uniondale, N.Y.] v. 2 #3, p. 10-11).

“His dedication to the preservation and communication of African culture led him to establish his ‘dream’—the Olatunji Center of African Culture. . . providing low cost classes in a wide range of cultural subjects to adults and young people.” – Office of Alumni Relations, Michael Henderson (a fellow alumnus, class of Morehouse 1965). Yusef Lateef (born in Chattanooga, Tennessee) played with Baba and talks of the experience in an interview conducted by musician Larry Ridley for the NYPL’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, September 27, 1996. (call number Visual VRA—181 Service Copy Sc Visual DVD 1065)

Fanga and Pearl Primus

Anyone claiming a serious interest in black dance, especially the traditions of the African diaspora in America must know about a dance called Fanga and the dancer/choreographer, Pearl Primus. Fanga is the first African dance many of us, this writer included, were exposed to and taught. This welcome dance was a standard performed at the top of every Olatunji Drums of Passion Show, after Ajaja, a processional number.

Photograph by Gerda Peterich.

The Trinidadian artist and activist learned the welcome dance in Liberia, where it originated and brought it back to New York where she lived and did most of her work. The Dance Division has more than 100 records of Pearl Primus, including reviews, photographs, books and more than 20 videos of interviews, dancing, or her choreography. Among them is an early film from Jacob’s Pillow of Spirituals [excerpt] choreographed and performed by Pearl Primus, 1950 (Destiné and Ramon, Primus, Shivaram, call number *MGZHB 4-363). There is also a nearly two hour video interview of Pearl Primus (Five Evenings with American Dance Pioneers : Pearl Primus, Third Evening , call number *MGZIDF 1466).

What Farah Jasmine Griffin says of Pearl Primus in her book Harlem Nocturne: Women Artists and Progressive Politics during World War II (available in NYPL’s circulating collection; call number: 704.042 G), applies to the significance that African dance would take on for many African Americans who came after her. She wrote:

Primus was not only engaged in a leftist political and artistic community, however; she was also part of a group of New York-based artists who wished to bring the culture of Africa and peoples of African descent to the attention of white audiences. Instead of evolving from a leftist to a black nationalist, instead of transitioning from an artist interested in social realism and modern dance to one interested in what would later be called "Afrocentricity," Primus always merged these political stances and aesthetic commitments. She did so by situating African dance alongside modern dance, and in so doing creating a dialogue between the forms, showing them both to be representations of a longing for freedom and human dignity. . . the language of dance to represent the dignity and strength of black people and to express their longing for freedom. Primus saw dance as a means of contributing to the ongoing struggle for social justice. (p. 31)

Photograph by Gerda Peterich.

The Dance Division has a video of Pearl Primus dancing Fanga (call number *MGZIDVD 5-6216) There is also a fifty-minute interview with Pearl Primus by Walter Terry (call number *MGZTC 3-110). James Briggs Murray of the Schomburg Center produced a videotaped interview with Primus documenting her early years in dance and anthropology and life growing up in Trinidad (call number Sc Visual VRA-71).

“Modern dance had been ensconced in radical politics since its formation; traditional African dance sought to give expression to the community’s history and aspirations. In creating a dialogue between these two forms, Primus helped to introduce a new context for the marriage of black aesthetics and politics. For Primus, traditional African dance and contemporary black vernacular dance were more than mere inspirations for modernist choreography; they were equal participants in helping to create a modern dance vocabulary.” (Harlem Nocturne, 2013, p. 25).

There is enough of a market and following for African folkloric movement to support classes seven days a week in New York, year in and year out. There are now dance conferences held from Maine to California and points in between such as Atlanta, Tallahassee, New Orleans, and Chicago. The students are artists of course, but they are also medical doctors, academics, scientists, lawyers, publishers, and more.

The teachers hail from and represent the nationalities of the various dance vocabularies: Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Congo/Zaire. These are among the most popular and influential teachers/choreographers/performers in this community. Most are based in the New York/New Jersey area, but others are scattered around the country. There are vibrant dance communities, for example, in the Bay Area and Los Angeles in California, in the Washington, D.C., metro area, New Orleans, and Atlanta, though none match New York in quantity and quality.

Finding Legacy in Dance

I apply the principle of sankofa—I look back in order to look forward—to sort out the roles of dance and the significance of traditional and ethnic dance in contemporary culture. The question is personal with me because dance is more than an individual interest or passion, it represents a way to make a living, an affirmation of identity, an aspect of ritual that is dynamic in home and the community—locally, globally, and historically. It is a way of getting to know myself.

“The Africans who came to Latin America, the Caribbean and the United States as slaves brought with them their own social, ceremonial and religious dances. Over the centuries these slaves descendants developed rituals and ceremonies, both social and religious, using dance as a medium of expression. Though rooted in the New World their dance derived from Africa.” — Alice J. Adamczyk, from the Introduction of Black Dance: An Annotated Bibliography (Garland Publishing, 1989) (call number *MGP 89-11473) .

Adamczyk’s Black Dance: An Annotated Bibliography is one of the best sources I’ve used. The book is a compilation of material on black involvement with dance in all forms—much of it found in the New York Public Library’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

One of the most surprising bodies of work discovered in this research project is the collection of Mura Dehn, a Russian woman who made film, wrote, and studied black American dancers and dance traditions and innovations. She became a documentary filmmaker and an artistic director of Traditional Jazz Dance Theater. She spent many years documenting social jazz dancing at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem in the 1930s. She’s best known for two films: The Spirit Moves and In a Jazz Way. The former is a history of black dance from 1900 to 1986; the latter is a biographical film about Dehn. The Dance Division has the four-volume recordings of The Spirit Moves (call number *MGZIC 9-743) and In a Jazz Way: A Portrait of Mura Dehn (call number *MGZHB 12-2407).

The Mura Dehn collection documents Mura Dehn's professional life as dancer, choreographer, scholar, and filmmaker and, to a lesser degree, her personal life through notebooks, poetry, and correspondence. Most important are the research notes and drafts of her many scholarly writings on the development of Afro-American social dance in this country. The following are quotes from Dehn's papers, which the library acquired in August 1987 (call number *MGZMD 72).

When Africans were brought to this country, the white Americans could not conceive that there was an African Culture. The tom-toms frightened the white masters. African drumming brought a liberating energy. It was too dangerous a weapon to leave in the hands of the slaves. The drums were destroyed and forbidden.

The African dance horrified the puritanical whites. They saw it as hideous contortions, lascivious, abomination and bestial sensuality. The celebrations in Congo Square in New Orleans were finally forbidden. From the start the most precious gifts of Africa were misunderstood and defiled. They were made to appear hideous even to the African slaves themselves.

—Mura Dehn, “Black Awareness Through Folk Art,” in the Dance Division as Papers on Afro-American social dance, circa 1869-1987 (call number MGZMD 72 - #120, Box 5, p.2).

My Family Dance Story

My earliest known ancestor who danced was John Green, my maternal great-grandfather, born in the late 19th century. I learned about him first from his wife, my great-grandmother, Allie Caldwell Green Rucker (married three times, there is another surname between that of Mr. Green and Mr. Rucker). But my grandmother Eula Lee Green Crump and her son, my uncle James Robert, aka J. R. Crump, all talked about him, giving me bits of information that fed my curiosity about the past, especially the history of my family and of dance—two things I love dearly.

John Green made his living dancing and taking advantage of whatever kind of—limited—work an early-20th-century black man was allowed. He often had to travel away from his home in East Tennessee to do so, hopping trains to get from one place to the other.

He took his wife and children along too, at least for a while. Mama Allie, as we called her, talked about how often he’d say, “Allie, there’s work in West Virginia,” letting her know he had to go. He did so one time too many and her reply was “okay, but I’m staying right here,” in Rogersville and Knoxville, two of the places where they had established roots and family.

John Green was a buck dancer who did some of his performances on stages at the circuses and fairs. Daughter Eula recalled to me the times during her childhood—after her parents separated—when a neighbor child would “run from town” to let her know “your daddy is dancing on stage.” She and her older brother and sister would run to see him. A love for dance and other arts runs through our family and a few, like John Green, made a little money not only dancing, but playing music and painting. Our women and men were quite talented but, as in the larger society, men had more opportunity and even credibility than women.

My grandmother Eula, John Green’s youngest, loved to dance. Buck dancing wasn’t her style, the Charleston was. She boasted to me—to my embarrassment—that she could "kick her legs over daddy’s (her husband’s) head." Alvin Lavon Crump was not a tall man, but nonetheless, the idea that my prim and proper grandmother would come even close to kicking her stockinged legs that high was impressive and shocking. Included in Papers on Afro-American social dance, circa 1869-1987 is an article titled, “Josephine [Baker] and [the] Charleston invaded Paris like a drug” (call number *MGZMD 72, box 5, folder 125).

I lived in my maternal grandparents' home to witness and hear these stories of how dance was woven into our experience and our history. My curiosity became a passion that grew as I did and led to me being the practitioner, student, and scribe of dance subjects that I am today.

Buck & Wing Dance

In most cases, when I brought up the subject of Buck dancing, family members and friends would roll their eyes, some saying, “I don’t want to know anything about that.” I understood the negative reaction: the name and dance itself in many ways represents the oppression of Black Americans. Buck is racist slang term for Black males and dance is a skill and activity stereotypically assigned to and associated with African and black Americans. So some regard it as simply the “natural” dancing done by black men in order to earn the coins of white audiences.

I've discovered in my research that there was much more to know about Buck dancing than the 52 steps, which Uncle J.R. got from his grandfather John Green. Uncle J.R. told me that John Green taught him 52 steps of the Buck dance. 52 steps suggested to me that what John Green did was more than improvisation (or free-styling as we’d call it now). For all of his boasting, I was never able to get Uncle J.R. to show me much. He remained a good looking, well-dressed man all his life, but an alcohol habit took most of his talent and ability to play music or dance. He’d do a few seconds on the piano, get up and show me a move and go on reminiscing.

Two moving image records in the Dance Division are:

- The History of Jazz Dancing , videotaped 1970, a lecture demonstration in which Les Williams presents the black man's role in the history of jazz dancing. Includes demonstrations of the Irish jig, minstrel dances, buck and wing, vaudeville dancing, modern tap patterns, discotheque dancing (call number *MGZIC 9-96).

- Old time dancing in the Appalachian Mountains (call number *MGZIDF 2217 ) Reel 6 (62 min. total). After the conclusion of Whisnant's speech (11 min.), there is "African-American traditions," a lecture-demonstration by John Dee Holeman and Quentin Holloway, with Friedland (44 min.). The lecture covers buckdancing, tap dancing, and the "tap Charleston." " Videotaped for the Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Philosophies of Dance and Innovation

“Learn neatly and with artistry. And then originate through yourself.” —A. L. Liegens, Savoy Lindy Hopper, from “Jazz Dancing: Folklore in the Making” (call number *MGZMD 72)

“When I did the Buck & Wing dance, we had to stick to a routine. If my teachers saw me miss a step he would hit me with a stick. My teacher was Rick Simmons of the team Simmons & Baby. They won first prize in a World Fair in St. Louis around 1900, doing 137 different steps in Buck dancing.” —Miss Lillian Brown, interviewed in 1960 by Mura Dehn (call number *MGZMD 72)

We were encouraged to study music, make things with our hands, and use our bodies to express ourselves. But, the latter had to be done with the utmost caution, the statements made with body movement, clothing and adornment could get you in—even deadly—trouble.

The following quotes from a paper titled “From the Horse's Mouth” are examples of the observations made by Mura Dehn (call number *MGZMD 72, box 5, folder 123).

“Questioning the Blacks about their Art I found that they seldom give a direct answer. They will talk about conditions of life, problems, religion, racial questions, jobs, philosophy in general and then conclude with a description of the Dance. All of which made me understand that their Dance was inseparably connected with life and only speaking about life could they convey the meaning of Dance. 9 (p. 2)

"The Black artist is in a process of making his own folklore—he does not inhereit [sic] it.” (p. 2)

“I learned that to the average Black, art is a proof of general ability. If they are good in art, they will be just as good in anything they become.” (p. 6)

The Spirituality of Dance

Theater, play-acting, was more common to my experience coming up in the Baptist and AME Zion Church in Tennessee, but I would hear references to a kind of sacred dance called the Rings Shout. In general though, religious dancing was an oxymoron in our world. You just couldn’t call movement in the name of the Lord dancing. You were very much supposed to move to gospel and spirituals, but “your feet can’t cross.” And, you certainly couldn’t use hips and torso.

What people did was “get happy.” They “shouted.” They would be filled with emotion or the Holy Spirit and express the joy of that with their bodies: some skipped, jumped, etc. I’ve seen a familiar quick step done by many who got the spirit. And, I’ve been thrown to the floor when great grandmother Allie jumped up from her seat as I laid my head in her lap during Sunday service.

The Ring Shout

When I learned about Ring Shout as an adult, a lightbulb went on. I was able for the first time to understand what people meant by saying it couldn’t be sacred dance if the feet crossed. The Ring Shout is characterized by a low shuffling of the feet and a slightly bent torso by a group of people moving in a circle. The arms and hands are deployed to deliver the specific message or story. Like many African dances that also happen in a circle, there is a time and place for someone to dance solo inside the ring. In the Dance Division there is a videotape of McIntosh County Shouters (call number *MGZIC 9-2698) recorded by the Dance Division through its original documentation project.

In 1786 the law forbade slaves to dance in public but in 1799 a visitor saw vast numbers of negro slaves assembled on the Levee dancing in large rings and an another Sunday inside the city upwards of one hundred negroes of both sexes were dancing and singing on the Levee.

Christian Schultz describes twenty different dancing groups of negroes: "They have their national music: a long kind of narrow drums of various sizes from 2 to 8 feet long, three or four of which make a band. The dancers and leaders are dressed in a variety of wild and savage fashion ornamented with a number of tails of the small wild beasts.”

—Mura Dehn (call number MGZMD 72 , “Night Life in Georgia,” Jazz Monthly 6, no. 9 [1960]: 11-12)

Swing

The Papers on Afro-American social dance, circa 1869-1987 from Mura Dehn (call number (S) *MGZMD 72), form a collection that, for its subject matter, is among the most rich collections housed in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division. Documents gathered in this collection—from media reviews of performances to interviews and oral histories of dancers and choreographers—cover the years 1869-1987.

She was a dancer herself and, for example, writes of being taught black dance, including ones called “the itch,” “the hammer,” and the “Havayan.” She saw the connections between these movements and those which were elements of dances originating in Africa. They were “very close to the basic African dance Asadata Dafora taught in our joint school, The Academy of Swing in New York.”

Standard Bearer: Joe Nash

This pioneer black and male ballet dancer, Joe Nash, served as a historian and researcher of black dance. In his later years he could be seen moving about Harlem wearing a fantastic African textile coat and kufi. He was a short man who moved with the grace of a king. There is a photograph of him as a young classical dancer, in a full split on the sand of a beach, having fun. He was a moving archive who documented and acknowledged with his work the contributions of dancers, choreographers, and dance companies from the 1930s to the 1980s. He brought together published and unpublished writing, art, lectures, and images about dance including ballet, modern African, African interpretive, and theatrical dance.

Understanding the Library’s Catalog

Researching in the library, I found the system of discovery in the Dance Division was difficult. Curator Jan Schmidt explained the library’s system of subject headings:

While black dance itself is a very large subject, in the Library, black dance encompasses many styles, genres, and countries and dance has styles and genres that are without relation to ethnicity or background, such as modern dance. The Library of Congress and the New York Public Library have developed subject headings that are specific. Searching the NYPL catalog using the subject heading Dance, Black, there are only 3,464 items. These do not include dancers, choreographers or companies that are mainly black. The subject Dance, Black refers to materials “about Black dance.” At the Dance Division, these searches of dance, Black will include such things as the DanceAfrica series from Brooklyn Academy of Music and The 8th International Conference of Blacks in Dance and Dance Black America II. [Talking Drums! The Journal of Black dance, vol. 5, no 1 (Jan. 1995), p.11-19, call number *MGZA].

So, Alvin Ailey in an interview tape about civil rights will have a subject heading as: Dance, Black—United States. But otherwise, in the performance videotapes, he will only be identified as choreographer. There are too many Africans and African Americans, to be included in such a large subject heading as Black dance, just as there are too many Caucasians or Asians to be in a subject Caucasian or Asian dance.

A keyword search of dance, African American, an older subject heading, brings up a list of 761 items, many of which are also contained in the dance, Black search. Under the subject heading Dance, Black, the materials are listed by state and sometimes city, such as Dance Black—New York (State)—New York. Here, for instance, you can find records like this more recent video from 2012: PLATFORM 2012 : Parallels, From the Streets, From the Clubs, From the Houses, curated by Ishmael Houston-Jones and presented by Danspace Project. [call number *MGZIDVD 5-7130].

What won't be under Dance, Black are the huge number of black choreographers, companies and dancers in all fields of dance. Though with a digital catalog, the issues of subject headings are less critical, in that keyword searches can often get a researcher to their desired materials. An example of the issues is that for such genres as tap dance, many of which could be labeled black dance not all tap dancers are black. Though Alvin Ailey is a major black choreographer, the library does not label him as such. So he will only be found under black dance when he is talking about black dance. A keyword search of Alvin Ailey brings up a list of 1,163 items. These may be about him, by him, of his choreography, his dancing. But they are not labeled Dance, Black unless someone in the article, book or tape is talking “about” the subject black dance. It also brings up another issue in black dance. If a Japanese group performs Alvin Ailey's choreography of Revelations, would that be cataloged as black dance?

If you look at dance directly from Africa, the subject heading Dance—Africa will get you to materials about the continent of Africa, not individual countries. A keyword search of Dance—Africa will bring up a list of 363 items. A subject search of "Dance--Africa"will bring up a list of 192 items. But this does not encompass the materials from or of Africa in the Dance Division, only the materials “about the continent of Africa and dance."

When you search by countries, for example Dance—Guinea, you will find 42 items, including 33 videos. One group of videos that are especially interesting are the 1991 documentation of part of a three-week trip to the interior of Guinea, made by Kemoko Sano and Hamidou Bagoura, respectively choreographer and technical director of Les Ballets Africains of the Republic of Guinea, in search of promising musicians and dancers who might be recruited for the company and source of material for new works. At each site they visited, they were received by local authorities, and watched local troupes. They are often glimpsed observing, recording, and occasionally taking part in the performances.

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Boké *MGZIC 9-5072

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Macenta *MGZIC 9-5069

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Lola *MGZIC 9-5068

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Mandiana *MGZIC 9-5071

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Nzérékoré *MGZIC 9-5067

- Dance of Guinea. Préfecture de Siguiri *MGZIC 9-5070

So searching the catalog of the New York Public Library is a complex process. Each time, new things emerge, new links to follow, new subjects to consider. Like black dance, the catalog has many genres, styles, and practitioners.

Asadata Dafora and the Birth of African Dance in America

Photographer unknown.

Another pioneer of African dance in the United States was Asadata Dafora, who arrived here in the 1930s. The Dance Division holds the register of the manuscripts and other items in the Asadata Dafora Papers, 1933-1963, MSS. 48 in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library. There are also a number of articles, clippings and photo files. The videos include re-creations of his most famous choreography, such as Spear Dance and Awassa Astrige. Parallel Visions: Design in Three Eras of African American Concert Dance (call number *MGZIC 9-4918) is a video of a symposium held in conjunction with the exhibition Onstage: A Century of African American Stage Design, presented in the Amsterdam Gallery of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts in 1995. In this video, among other speakers, Richard Collins Green, using examples drawn from the 1930s and 1940s, explores questions of the relation of dance design to the aesthetics of its time. Among the dancers and choreographers he discusses are Asadata Dafora, the Hampton Creative Dance Group, Pearl Primus, and Katherine Dunham.

African Dance Spaces and Community

African Dance spaces and the communities that have developed within them constitute one of the most diverse art and culture scenes ever—racially, ethnically, and otherwise. Survey the faithful who’ve attended classes and events around dance several times a week for decades and you’ll find Iranian, Swiss, German, Italian, Argentine, Polish, Russian, Japanese, representatives of every corner of Africa and the Diaspora. These—mostly women— are doctors, lawyers, teachers, scientists, artists, stay-at-home mothers, retirees, and teens. Some are professional dancers or were, many have migrated over to the African styles from more Western-centric ballet and modern, but many began their dance experience with African and it stuck.

The understanding and execution of the movements of traditional dance is not easy for most. They are often intricate, quick, and demanding. But, unlike European ballet, they are kind to the body, not requiring that it be molded and manipulated in unnatural ways, as is the case with dancing on pointe. The vocabularies are extensive and varied, they cannot be easily characterized and break through all stereotypes. And, they are dynamic, the styles, the cultures change from one generation to the other, one community (even inside Africa) to the other, one family to the other.

The cultures and nations represented in these schedules of classes include: Brazil, Congo, Cuba, Egypt, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Mali, Nigeria, and African America. And these are primarily the geographical references for this journey into the documentation of what this writer refers to as black dance.

Black refers to race, a construction maybe, but one that effectively links people to the common experience of racism. The black body, especially outside of our own environments, finds itself in unique conflict with the dominant culture, because we tend to have a physicality and worldview more in common with each other than with non-blacks.

There is a treasure trove of documents, information, and especially images of great dancers and great dance moments in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division—a sample represented here. Get familiar with the classification system, follow your instincts and interest, and you’ll find them. You’ll uncover much more though by getting to know and working with the staff.

Librarians and support staff will understand the nuances and quirks in the way items are organized and maintained. I am an alumnus of the Atlanta University School of Library and Information Studies, who has worked in public and private libraries and learned the value of the training librarians receive and the passion they often have for their work. You can learn directly from them as keepers of the documentation who often can even tell you how items came to the library’s collection.

Items in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division

- Dinizulu Dancers and Singers (Company) no. 6, call number *MGZEA

- Katherine Dunham, no. 5, call number *MGZE/MGZEA

- Lavinia Williams, [Clippings], call number *MGZR

- Sara Yarborough, no. 3, call number *MGZEA

- Eleo Pomare, no. 5, call number: *MGZEA

- Eleo Pomare, no. 6, call number: *MGZEA

- Eleo Pomare, no. 9, call number: *MGZEA

- Charles Moore, no. 1, call number *MGZEA

- Dinizulu Dancers and Singers Company no. 4, call number *MGZEA

- Babatunde Olatunji and Company no. 4, call number *MGZE

- Babatunde Olatunji and Company, no. 5, call number *MGZEA

- New York Public Library Digital Collections, Image ID: 1225989

- Asadata Dafora, no. 1, call number *MGZE

- Pearl Primus, no. 7, call number *MGZEA

- Pearl Primus, Portraits, no. 2, call number *MGZEA

- Asadata Dafora, no. 17, call number *MGZE

Malaika Adero is a veteran editor in book publishing and author of Up South: Stories, Studies and Letters of This Century's African American Migrations (The New Press 1992-93) and coauthor of Speak, So You Can Speak Again: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston with Dr. Lucy Hurston. Publisher and founder of Home Slice magazine (www.homeslicemag.com). She is a former vice-president and senior editor at Simon & Schuster. She has worked with several dance companies, including Almamy Dance Ensemble and Babatunde Olatunji's Drums of Passion.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Black Dance Narratives

Submitted by Yvonne Hilton (not verified) on May 6, 2016 - 5:06pm

Amazing work! Thank you for

Submitted by Collette Hopkins (not verified) on May 11, 2016 - 7:05am