Seward Park 100 Years Ago: Esther Johnston's Lower East Side

One hundred years ago this coming May Day, a woman from a small town in Indiana named Esther Johnston began her first day of work at the Seward Park Library on the Lower East Side—her term at Seward lasted from 1916-1921. She eventually became the head of The New York Public Library's Circulation Department until her retirement in 1951. Yet, despite her triumphs in the upper echelons of library administration, the Lower East Side must have taken a strong hold on her. In September of 1966 she wrote an article for the Bulletin of the New York Public Library entitled "A Square Mile of New York" which recounted her experiences as a librarian on the old East Side.

In 1966 it had been a full fifty years since Ms. Johnston had begun work at the Seward Park Library. While some things had obviously changed for the better, change is a very complicated animal. Johnston states,

"[I could] scarcely make it through the rubble of once-familiar streets and find the buildings that were landmarks. East Broadway, the street I knew best, has been breached as by enemy bombing."

It was a time of big ideas and big projects in government. Slum clearance ordinances and new housing for lower and middle income residents had been erected throughout the Lower East Side replacing the dilapidated conditions of the old tenements. The dreams of Lillian Wald, Charney Vladeck, and LaGuardia were coming to fruition. Johnston recalls that the three cultural powerhouses of the old East Side on East Broadway still survived—The Educational Alliance, the Forward building, and, of course, the Seward Park Library. Though the Forward building has been converted into condominiums, this proud architectural triumvirate still stands tall (though dwarfed by Coops), not as a reminder of a bygone era but as a part of the architecture of a community that still manages to thrive despite the ceaseless change integral to the East Side.

Johnston recalls the Seward Park Library of a hundred years ago as a place where children of many different backgrounds rushed to borrow easy books and fairy tales (particularly Andrew Lang's Fairy Book Series), while adults journeyed upstairs to the third floor to borrow from collections of many different languages. In 2016 this remains as true as ever—whether after school, on a Saturday, or during New York's sweltering months of summer, the branch is teeming with children who read everything from Geronimo Stilton to Dork Diaries to Edgar Allan Poe to Doraemon in Chinese. Graphic Novel serials of the Monkey King (a tale originally written by the Chinese Classical author Sun Wukong) can barely stay on the shelf long enough to shed the presence of the last borrower. Finding a seat can often be a trying task! It is only by the grace of our Out of School Time afterschool program that we aren't even more crowded.

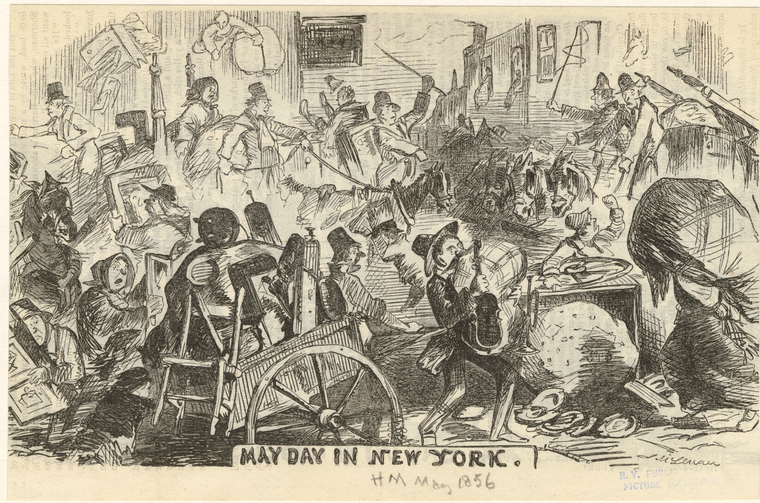

On her first day, Johnston was greeted by a Miss Ernestine Rose, a women truly dedicated to her patrons and instrumental in procuring a collection which reflected its majority immigrant Eastern European Jewish constituency. Rose would eventually bring her talents to the 135th Street Branch, renamed in 1951 after Countee Cullen. The May Day crowds in 1916 were such as she could barely make it to the branch's entrance! From this point on, this small-town woman would take various routes to work through the busy thoroughfares of the Lower East Side, navigating her way through the crowded slew of streets whose English names (Essex, Rivington, Norflok &c.) still pepper the area, specters of past generations, names which became bywords for sordid conditions and slum housing. Johnston recalls Irish families on Oliver Street, gypsy families (according to Johnston...) on Pitt Street, Armenians and Syrians who enjoyed their coffee in Chatham Square—As a Los Angeles native, I thought Lala Land was the only place to get a decent Armenian coffee!

The Second Avenue Elevated which Johnston used to ride home after an exhausting, (over)stimulating day at work was taken down in 1942. But the principles of the library that Johnston cites haven't changed all that much:

"Children growing up in New York [were to be] assured a hospitable welcome to the world of books. A child from a bare tenement could have as broad a range as the ones from bookish homes, limited only by poverty of imagination and unclean hands."

Sure—the Seward Park Library doesn't really check for clean hands any longer but the importance of access to information is still paramount to our mission. At Seward and its neighboring Chatham Square Library, merely a stone's throw away at 33 East Broadway, books circulate faster than can be kept up with, and computer terminals are constantly filled with users doing school projects, filling out e-government forms, or messing around with Minecraft. Some patrons simply enjoy our free internet on their own devices. In an era where 27% of New Yorkers still lack a household internet connection, access remains an important service. Not to mention our plethora of databases which ensure that access to information is as rich as it is available.

Johnston mentions that the fairy tales the children read,

"[...] enthralled these children of sweatshop workers and union members as they bathed in the golden light of imagination. Their heroes and villains were not union leaders and capitalists, not labor commissioners and racketeers, but kings and queens, princes and Cinderellas, wise fairy godmothers and wicked stepmothers whose punishment was always meted out to fit the crime."

Our children's staff is still blessed with the understanding it takes to serve a children's room of jostling, pushing, and snatching of popular titles, even if the old murals on our walls of Sir Galahad, Venice, and Robin Hood which inspired the children of the East Side a hundred years ago have been painted over, replaced with Chinese hanging scrolls which exhort the values of literacy.

And the story hours! Johnston recalls a weekly story hour where children reeking of rubber, garlic and dill were packed into the basement floor to hear the folklore of many countries. These days our busy story hours are even more frequent, multiple times a week, every session in our children's reading room filled to capacity. Children are serenaded by stories and songs in English and Mandarin, and the tunes of the otherworldly Raymond Scott's "Portofino II" and Cab Calloway's unparalleled "Everybody Eats"

After school the library continues to flood with youth of all ages just as it did in 1916. Johnston recalls having to shush teens on the reference floor, their unquenchable need for chatter and attention notwithstanding. Boy, do things never change—though these days we have much more for teens to do. Whether it's jewelry crafts, anime club, films, homework help, or any number of things you may be able to think of, young adult patrons are at no loss for what to do at the library. Maybe one day we'll bring back a more inclusive iteration of the Young Men's Debating Club, which, according to Johnston, used to completely fill the basement. Marx, Tolstoy, and Veblen were popular authors for debate in those days. Today, would we be more likely to discuss Žižek, Yanagihara, and Coates? Perhaps the effects of social media? Affordable housing?

Johnston continues her essay with a passage on the difficulties of keeping up with the foreign language readership, particularly Yiddish. While some things have changed, many haven't. The older gentlemen on our reference floor tend to read the Chinese Sing Tao Daily, World Journal, or China Press rather than the Yiddish Forward or the Jewish Day. Our Yiddish collection has shrunk from 2,287 titles in 1960 (which had shrunk from a whopping 7,560 in 1940) to a mere small shelf, while our large Chinese collection continues to grow at an incredible rate to meet the demands of our patrons. On sign-up days our English classes have long lines of language learners which extend out the door of the library! Johnston even recalls adult English language learners picking up some of the children's Easy Books to learn the language—a practice which continues to this day.

What would the Lower East Side be without the Settlement Houses? The Educational Alliance, Henry Street Settlement, University Settlement, all three get a mention in Johnston's little memoir of the old days—The Seward Park Library still works closely with these organizations to promote the ideals of literacy. Johnston remembers the spectacular quality of the plays Henry Street Settlement's Neighborhood Playhouse on Grand Street. And back in Johnston's day, visionary Lillian Wald (who was responsible for establishing Seward Park, the first municipal park in the U.S.) whose beaming personality and benevolence drew community organizers from all over the East Side to her dinner table, was an active force for cleaning up the slums and advocating for affordable housing with all mod cons.

In her final passages of the essay, Johnston says that "the old East Side has all but vanished", citing changes from pushcarts to markets (the Essex Street Market was built in 1940 during the LaGuardia administration to replace the pushcart system), from tenements to Cooperatives, as well as changes in demographics. What shocks me most is the fact that in 1966 the third floor reference room was closed to the public! Johnston says,

"A younger flabbier generation has not the stamina to climb two long flights of stairs nor quite the insatiable appetite for study."

The ancient House of Sages was still there in 1966 as it still stands today in 2016 (I pass by it every Friday on my way to read to my favorite class of first graders at PS 134 Henrietta Hzold), but the old men with earlocks reading in Hebrew and Russian as well as bewigged women on park benches had already began to wane in '66. She cites undreamed of affluence of professionals such as doctors and dentists living in the cooperatives of East Broadway alongside rubble and ruin soon to be developed. Above all, the East Side of 1966 was,

"[...] tentative and in transition [...]. Most of the dark old tenements with dingy kitchens and hall toilets have given way to apartments with modern bathrooms and kitchens and sun in the living-rooms. The children are rosy-cheeked and healthy. In time shrubs and trees may screen the rawness of new brick. The apartments have undreamed of conveniences, laundries, carpentry shops and social rooms, but let us admit that they are dully like most other developments and projects. It takes time and roots for neighborhoods to form new personalities and develop strong characters."

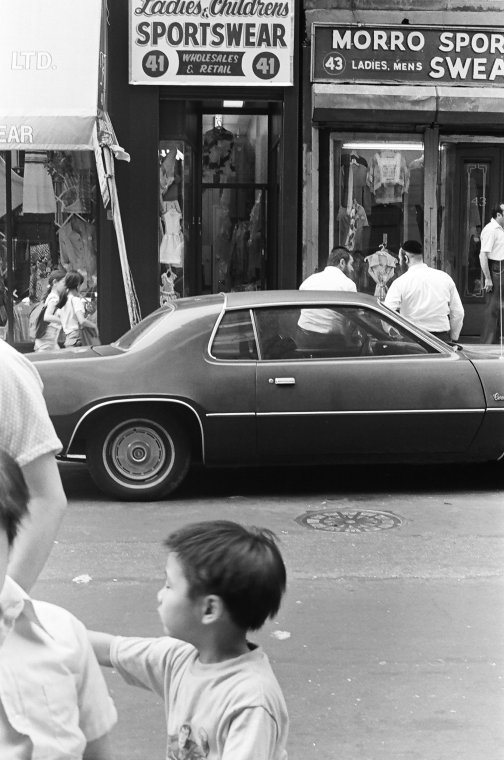

As a transplant from Los Angeles who doesn't know any better, I can't rightfully comment on the changes Johnston speaks of. Yet, when I walk the streets of Johnston's East Side they still teem with peddlers of all sorts, though this activity is farther west than it used to be, perhaps. In the past hundred years, synagogues have been replaced by Buddhist temples, Orchard Street has become a street for art galleries and fancy boutiques rather than discount garments, though a few shops do remain.

If we take Esther Johnston's memories as a standard, it's the library that has stayed the same more than anything. Our rooms are filled with patrons looking for entertainment, a place to work, or just to get away from the ruckus of noise and the pressures of constant push and pull of everyday life—is this really all that different from 1916? Here you may enjoy programs as diverse as morning tea and biscuits twice a week, Microsoft Office classes, Friday afternoon karaoke, or an evening film. We have computer and resume help, art exhibits. Your children, even more frequently than the children of a hundred years ago, may count on story times, arts and crafts, a good book, and even more amenities that weren't available in the library of yore. In a time where its harder to find a quiet place to read and work, where literally every shop is playing music to make us spend spend spend, where advertisements (or even our smartphones) are telling us what to buy, wear, eat and shop, the library offers opportunity itself—we are simply available to the public, and its a public we respond to and believe in. Indeed, libraries' faith in a Democratic public stands firmly against some of the more prevalent cynicism we see in America today.

Back in Johnston's day, artistic luminaries like author Anzia Yezierska, stage designer Boris Aronson, and playwright Bella Spewack frequented the Seward Park Branch. This was a generation that furnished a truly heroic age of American culture, from Hester Street to Hollywood. Who's next?

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

This is a thoughtful, well

Submitted by Guest (not verified) on April 19, 2016 - 9:21pm

NYC History and Culture

Submitted by David A. Martin (not verified) on April 20, 2019 - 12:31pm