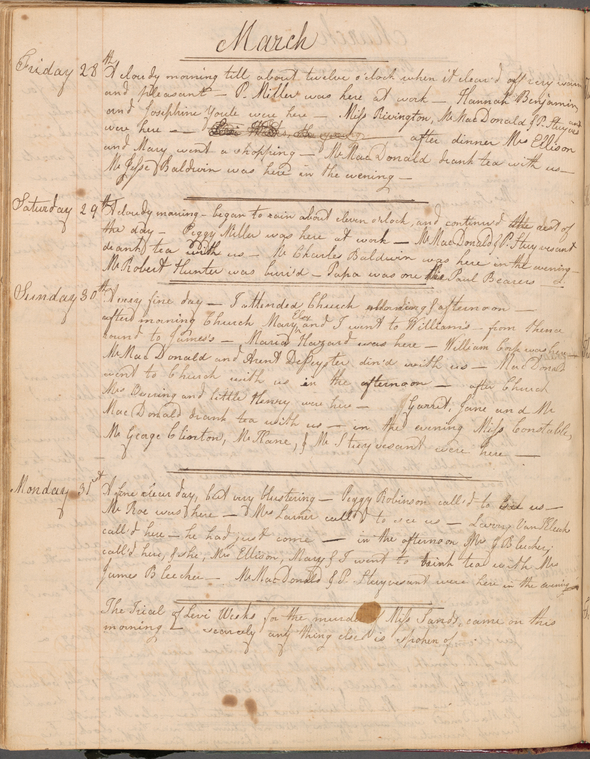

Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker Diary, March 31, 1800

“The trial of Levi Weeks for the murder of Miss Sands, came on this morning … scarcely anything else is spoken of.” Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker, March 31, 1800.

For many New Yorkers, the O.J. Simpson murder case will be forever linked to the New York Knicks. Tuning in to watch game 5 of the NBA finals, on June 17, 1994, viewers found the game in a small box, while footage of the police slowly pursuing Simpson’s white Ford Bronco took up most of the screen. This is when the Simpson murder case became a public spectacle and a signal moment in American pop culture. Americans can’t seem to shake their fascination with the case.

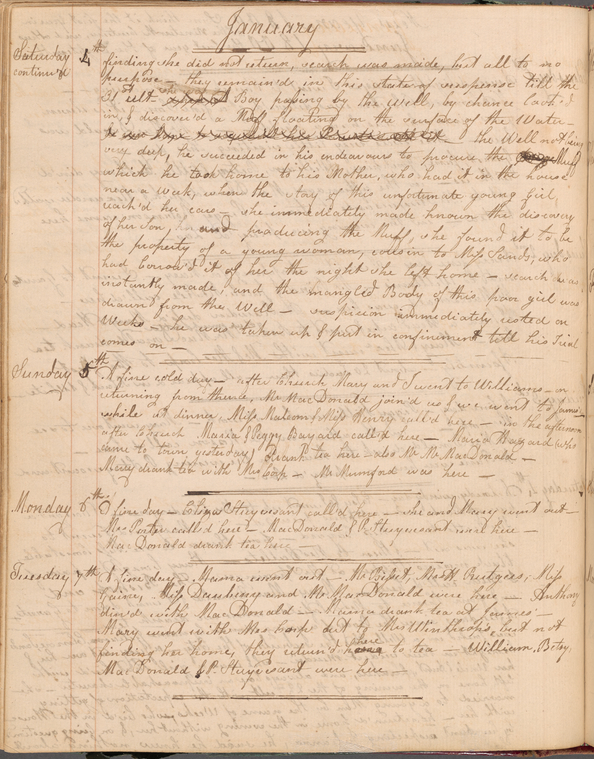

The murder that Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker described in this diary entry was an O.J. moment for its own time. Bleecker had been following the case for a few months. Sands had disappeared from her boarding house on December 22. On January 4, 1800, Bleecker noted that “A few days since the Body of a young woman ... was found in a well,” after a young boy noticed a piece of Sands’s clothing nearby. Once they pulled her “mangled body” from the well, authorities determined the young woman had been murdered.

The grizzly details captivated the city The owners of the boarding house where Sands lived even displayed her body for a few days for curious onlookers to come view.

Suspicion soon fell on Levi Weeks, a well-to-do young man who boarded at the same house as “Elma,” and who may have been courting her. Alexander Hamilton led a crack legal team representing Weeks. Aaron Burr was another of the defense attorneys. He probably took an interest in the case because Sands was found in a well owned by the Manhattan Company, which Burr helped to found.

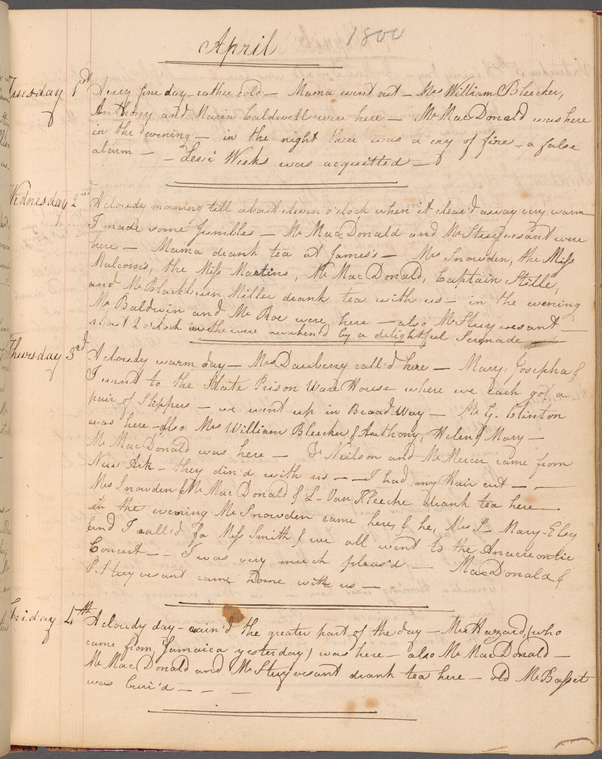

Bleecker made note of New Yorkers’ rapt interest on March 31, 1800, the day the trial began. It did not take long for the jury to reach a verdict. A day later, on April 1, Bleecker noted in her diary, unceremoniously, that “Levi Weeks was acquitted.” Weeks’s acquittal actually came at two o’clock in the morning; so it was technically on the 2nd. It’s not clear whether Bleecker found out about the jury’s verdict in the middle of the night or first thing the next morning. Either way, word traveled fast.

We know the Weeks murder was a big deal. The circumstances of the crime and the involvement of prominent attorneys ensured that it would be. It seems to have inspired some fiction at the time. And the case certainly received wide attention in newspapers. William Coleman, the court clerk, even kept a transcript of the trial, which was published later in the year. In perhaps the least surprising bit of New York trivia ever, a year later, Coleman became the first editor of the New York Evening Post, which is still published as the New York Post. Some things in New York have remained constant, and the Post’s sensationalism is evidently one of them. We can only imagine what the headlines might have looked like.

It will be rather easy for historians to pinpoint precisely when and how the O.J. Simpson saga became a pop culture phenomenon. Thanks to Nielsen Ratings and the like, we know that about 17 million people watched O.J.’s infamous chase unfold in split screen during the NBA finals. ESPN eventually made a documentary about that June day, cementing the cultural memory of the whole affair. There were no Nielsen ratings in 1800, and we don’t really know how people followed the Weeks story, in the press or otherwise. But the Bleecker diary offers a quick and suggestive glimpse into how the story of this murder, and sensational gossip more generally, moved through the streets of New York City. Bleecker’s diary provides a small but critical piece of evidence for how the Weeks murder trial transformed into the “Manhattan Well Tragedy,” a touchstone in the cultural memory of nineteenth-century New York.

This is the second in a series of monthly posts highlighting entries from the Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker Diary. Previous posts in the series include a broad overview description of the diary, and a post highlighting an entry from February of 1800.

About the Early American Manuscripts Project

With support from the The Polonsky Foundation, The New York Public Library is currently digitizing upwards of 50,000 pages of historic early American manuscript material. The Early American Manuscripts Project will allow students, researchers, and the general public to revisit major political events of the era from new perspectives and to explore currents of everyday social, cultural, and economic life in the colonial, revolutionary, and early national periods. The project will present on-line for the first time high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it will also make widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations. Over the next two years, this trove of manuscript sources, previously available only at the Library, will be made freely available through nypl.org.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Levi Weeks

Submitted by Dr. Hank Citron (not verified) on July 6, 2016 - 7:51pm