Spotlight on the Public Domain

Public Domain Theater: The Black Crook

This is one of a series of blog posts related to the NYPL Public Domain Release: discover the collections and find inspiration for using them in your own research, teaching, and creative practice.

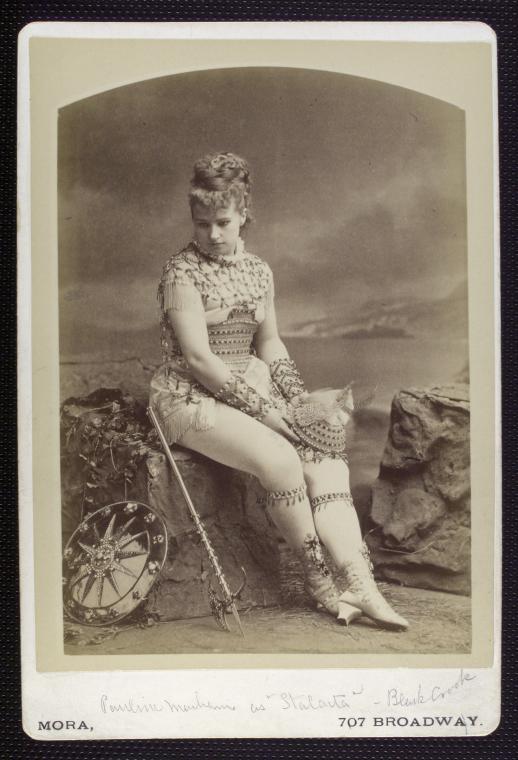

One hundred and fifty years ago this May, a fire destroyed the Academy of Music on 14th Street and Irving Place. Theatrical producers Henry Jarrett and Harry Palmer had planned to use the venue in the fall for a spectacular extravaganza, employing the dancers from a French production of La Biche au Bois and scenery from productions they had seen in England on a European tour the previous winter. The producing team had only returned to New York in April with their contracts already signed, and so, when the theater burned down, they had to move quickly to find another venue. William Wheatley, manager of Niblo’s Garden, agreed to have the ballets inserted into a production of The Black Crook—a melodrama for which he had recently purchased the rights. The piece was a hit—in part because some in the press (with various motivations) condemned it as indecent because of the tight-fitting costumes of the ballet dancers.

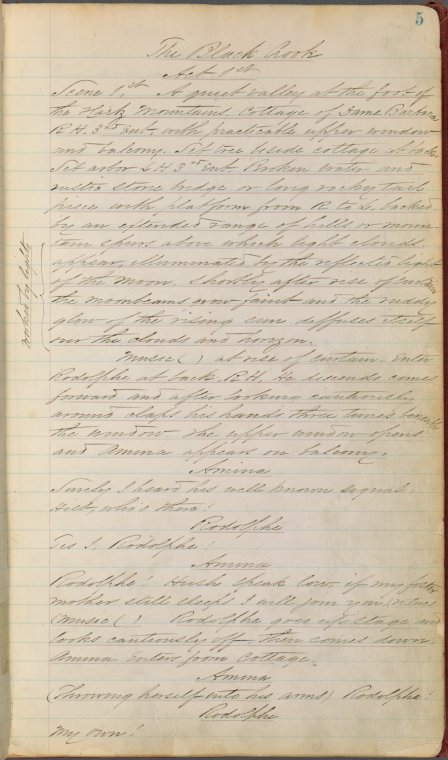

I have written about The Black Crook several times before, and have published several digital editions of the text and images of the sheet music associated with the original production. Over the years, the library has also digitized and made available several photographs of the casts of early productions, as well as our copy of an early prompt script. This month, thanks to the Library’s release of all of our high resolution photographs of objects with no known U.S. copyright restrictions, the promptbook, the sheet music, and the photos may be used without restriction for any purpose, including commercially.

The text of the play itself, and the sheet music published before 1923, have been in the public domain for some time, but now we’re providing our high resolution images of these objects that can be used for any purpose at all. This means that anyone who wants to publish and sell a facsimile edition of our 1866 prompt book (perhaps even using our copies of the sheet music and photos of the original cast) can do so, using our best images, without asking anybody. An enterprising director could stage a revival of The Black Crook and use these photos as projections in the scenic design or in the program without restriction.

You can also copyright your own innovations based on these images. For instance, soon after we published the sheet music online, Adam Roberts and a team of singers in Austin, Texas, performed several songs and released them under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license, which means that you can freely share the recordings, but you can’t sell them without his team’s permission. You too could record yourself performing the play, and the copyright of the recording would be yours.

All of this is possible because the U.S. Constitution allows Congress to pass laws “securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” in order “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.” In 1856, Congress extended this protection of “science” to the plays, allowing "the proprietor of dramatic compositions, designed or suited for public representation...the sole right to[...] act, perform, or represent the same.”1 The idea is that those who create should enjoy, for a limited period of time, the exclusive ownership of their work. However, the hope is that, once published, and “a limited time” has passed, new creations may be freely built on the foundation laid by others. I’m hopeful that, on this 150th anniversary of this piece that figures so prominently in musical theater history, theater companies around the world will take the opportunity to stage this piece for which so much production material has now been made freely available.

1) In 1867, though, a judge in California decided that The Black Crook was so lewd it was not, in his mind, “suited for public representation.” He therefore refused to extend copyright protection to the play.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

The Black Crook

Submitted by Harrison & Lind... (not verified) on February 23, 2016 - 12:53pm