The Natural History of Early Modern Needlework

Nineteenth-century literature is full of anecdotes about women’s involvement with needle point. In Mansfield Park, Jane Austen describes one of her characters:

To the education of her daughters Lady Bertram paid not the smallest attention. She had not time for such cares. She was a woman who spent her days in sitting, nicely dressed, on a sofa, doing some long piece of needlework, of little use and no beauty, thinking more of her pug than her children, but very indulgent to the latter when it did not put herself to inconvenience […].

An engaging, if disagreeable character, Lady Bertram, more interested in the superficialities of her appearance than in weighty matters of the mind, crafts ugly embroideries while decorously positioned on a settee, no doubt engaged in light conversation or listening to a novel being read. Austen’s vivid account succinctly points to the way in which (in collusion with mothers themselves!) women’s education was given short shrift. Encouraged to become “accomplished” in speaking modern languages, playing a musical instrument, singing, and executing water colors, nineteenth-century women were only on the rarest occasions granted access to institutions of higher learning and were thus never exposed to the sorts of rigorous classical educations men enjoyed. Needle point, Nathaniel Hawthorne points out, reflected their creators’ virtue and was thus a fittingly feminine attribute and a complement to womens’ other “accomplishments”:

“Methinks it is a token of healthy and gentle characteristics, when women of high thoughts and accomplishments love to sew; especially as they are never more at home with their own hearts than while so occupied.”(The Marble Faun)

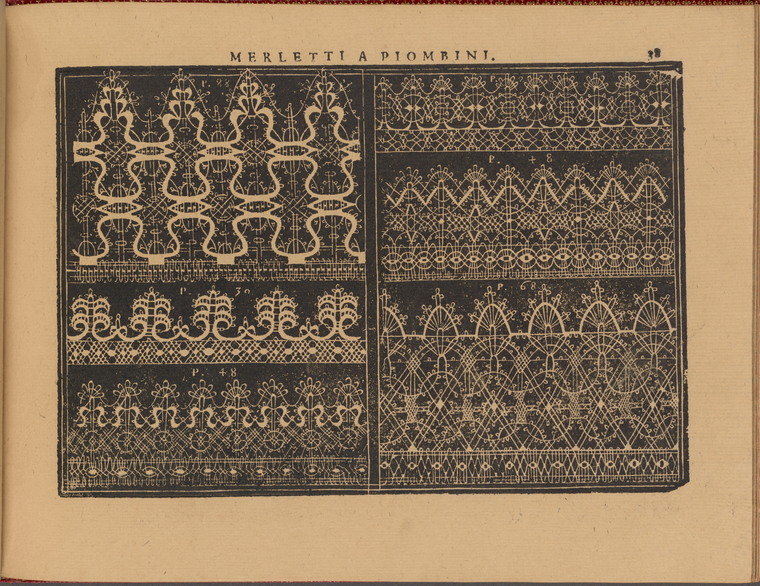

While texts like these reinforce our association of needlepoint with the feminine “labor” of the upper classes, what we may forget is that the patterns women needed to produce their work were mostly designed and created by men from the sixteenth century on. The development and execution of printed needlework patterns by two early modern women is pioneering in this regard. Isabella Parasole’s (c. 1570-1620), Teatro delle nobili et virtuose donne [Theater of Noble and Virtuous Women], included in the exhibition, Printing Women, and Maria Sibylla Merian’s (1647-1717) Blumenbuch [Book of Flowers] were created by women for women.

The title page to Parasole’s work features an elaborate sculptural strap work frame ornamented with four putti and two trumpeting angels.

A portrait of a woman dressed in a high collar ornamented with pearls, who has been identified as conflating the identities of the dedicatee, Elisabeth of France (1602–1644), and the creator herself who here calls herself, not Isabella but Elisabetta, can be find at the very bottom of the page. Directed at “noble and virtuous women” the title asserts the virtue of needlepoint and alludes to its execution by high-born women.

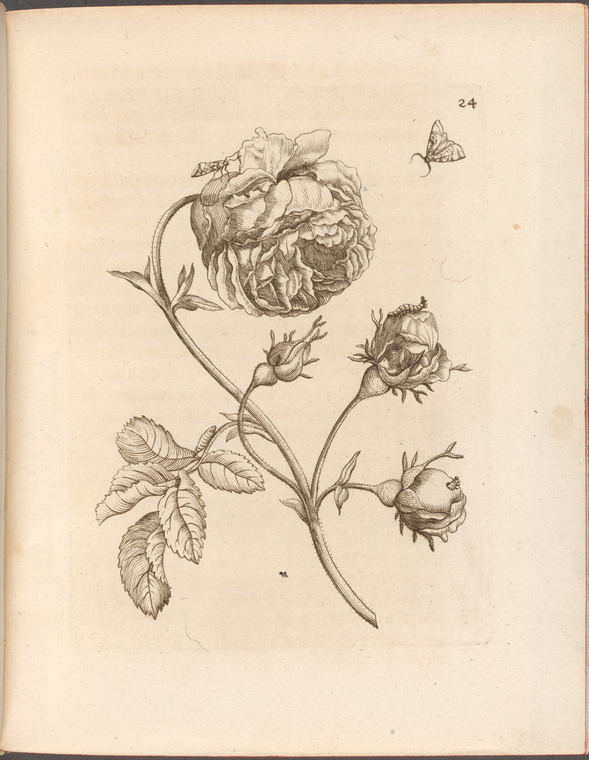

Not in the exhibition is Maria Sibylla Merian’s Blumenbuch [Book of Flowers], published in three parts in 1675, 1677 and 1680, which the artist developed as patterns for women’s embroidery. Following the death of her birth father Matthäus Merian the Elder, Maria Sibylla grew up in the household of Jacob Marrel, her mother’s new husband. Marrel, an accomplished painter of highly detailed floral still-lives mentored his step daughter in the arts. Indeed, Maria Sibylla’s fascination with flowers is in large part indebted to her stepfather’s own work, which included meticulous renderings of tulips and other naturalia. Shown in the exhibition is Maria Sibylla’s slightly later Raupenbuch [Book of Caterpillars], published from 1679-1683, and whereas the former is construed as a pattern book, the latter is acknowledged as an important example of early modern natural history.

In his poem “The Praise of the Needle” composed sometime between 1629 and 1631, John Taylor wrote of the importance of needlework in the lives of 17th- century women. Excerpted are a few lines from the poem:

Flowers, Plants and Fishes, Beasts, Birds, Flyes, and Bees,

Hils, Dales, Plaines, Pastures, Skies, Seas, Rivers, Trees,

There’s nothing neere at hand, or farthest sought,

But with the Needle may be shap’d and wrought.

Taylor takes the conventional topics of natural history, the flora and fauna of near and distant lands, to be the subjects of needlework. It is no accident, therefore, that the other area in which Isabella Parasole excelled was likewise related to an important work of natural history. The 17th-century painter and art historian Giovanni Baglione wrote that Isabella supplied the botanical illustrations to Prince Frederico Cesi’s Rerum medicarum Novae Hispaniae thesaurus [Treasury] (Rome, 1651). It is likewise fitting that Maria Sibylla later traveled to Suriname, where she documented the jungles of jungles of South America seething with unknown specimens, resulting in the important publication, The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname.

In developing designs for so-called women’s work, these two artists entered into the arena of exploration and discovery usually considered outside of the sphere of women, a fact that may explain why none of Isabella’s illustrations for Cesi were ever signed.

Key Literature:

Lincoln, Evelyn. "Models for Science and Craft: Isabella Parasole's Botanical and Lace Illustrations, " Visual Resources, 18 (Winter, 2001): 1-35.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Needlework

Submitted by Ellen (not verified) on October 6, 2015 - 11:10pm