Musical of the Month

Musical of the Month: Little Nemo

A guest post By Brian D. Valencia

In one of two overblown patriotic spectacles, the Act 2 finale of Little Nemo explodes with a burst of fizzy stage pyrotechnics as the company sings a hymn to the Liberty Bell. It has already sung paeans to Fourth of July fireworks and the “heroes of ’76,” and conducted a dubious lesson on the history of the holiday. (“Now where was the Declaration of Independence signed?” Answer: “At the bottom!”) These flag-waving festivities, thrilling as they surely were for the show’s original audiences, quite literally have nothing to do with the action of the musical, which presumably takes place over one or two days and nights… during which it is also, apparently, May Day and Valentine’s Day. Are these incongruities the result of lazy dramaturgy? Can they be chalked up to the usual attention deficit of the pre-“integrated” musical? Or might they be forgiven altogether, since it’s all just a dream, anyway?

Already at the turn of the twentieth century, the “serious” drama of Europe was ardently exploring the theatrical potential of dreams. By the 1880s, the self-proclaimed symbolists began mining the dramatic potential of the subconscious mind, overturning the melodramatic playwriting models that had dominated Western stages throughout the 1800s, and departing substantially even from the new vogue for realist and naturalist plays and performance styles. The American musical theater remained almost entirely untouched by these developments. But fewer than eight years after the original publication of Sigmund Freud’s influential psychological study The Interpretation of Dreams and fewer than seven years after August Strindberg wrote A Dream Play, Little Nemo—a theatrical work of dreams of a whole other order—opened on Broadway at the opulent New Amsterdam Theatre on October 20, 1908, after a three-week tryout in Philadelphia. According to the New York Times, the city had “seen nothing bigger or better in extravaganza than ‘Little Nemo.’” It had also never seen a theatrical production more expensive.

Little Nemo (presumably named after Jules Verne’s submarine captain in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) officially began life in the funny pages of the New York Herald on October 15, 1905. There, in a weekly full-page comic strip, cartoonist Winsor McCay drew the wacky, often disturbing sleepy-time adventures of a seemingly ordinary little boy with an extraordinary nighttime imagination. Following incredible romps with fantastical creatures through dazzling, dizzying perspective landscapes, the final panel of each week’s installment always showed Nemo waking suddenly to the call of his parents—usually having fallen out of bed at the violent climax of the bizarre dream.

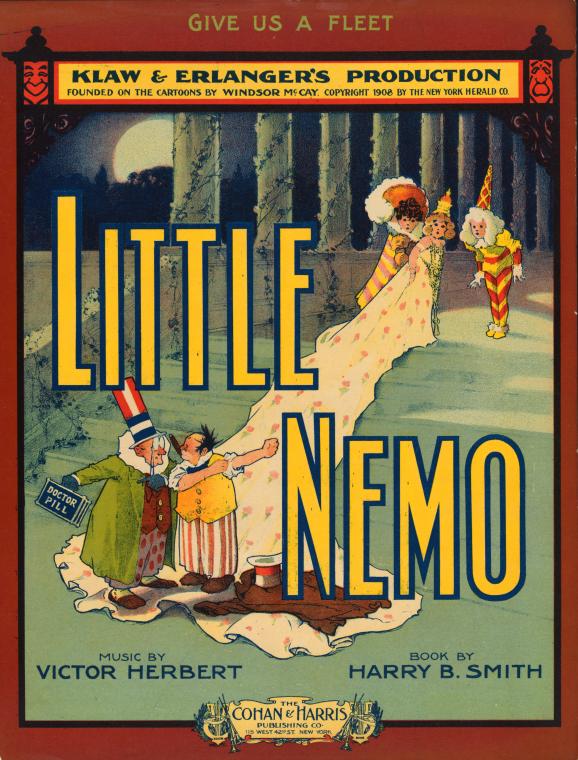

Almost immediately plans were made to adapt McCay’s comic strip for the stage. No lesser figure than Broadway impresario, producer, and playwright David Belasco set about translating the wild impossibilities of Nemo’s episodic capers to a satisfying evening of theater, but neither he nor three other playwrights making early attempts could lick a script. In 1907, however, Marc Klaw and Abe L. Erlanger—arguably the most powerful American producers of the day, sitting at the head of the notorious Theatrical Syndicate touring monopoly—acquired the rights for Little Nemo. Before they had even named a creative team, they announced their “operatic spectacle” would take the form of “a series of monstrous tableaux,” constructed with an unprecedented budget of $100,000 (approximately $2.5 million in today’s dollars). The Viennese operetta The Merry Widow, which preceded Little Nemo at the New Amsterdam Theatre in 1907, was a very expensive production for its time, but it had still cost less than $35,000 (about $870,000 today). Klaw and Erlanger boasted publicly that they would not only recoup their initial investment, but that they would see it returned fivefold. They never did.

The impulse to produce such a lavish affair was no doubt at least partly inspired by recent great successes of musical fantasy on the Broadway stage. Following L. Frank Baum’s (and Paul Tietjens’s and others’) musical adaptation of The Wizard of Oz (1902/3) and Victor Herbert and Glen MacDonough’s Babes in Toyland (1903), the moment seemed ripe for sweeping, family-friendly (cash-raking) musical fantasy. Given the lasting popularity of his whimsical Babes in Toyland score especially, the prolific Victor Herbert was the obvious choice for Nemo’s composer; at the time, he was still riding high on his back-to-back successes of Mlle. Modiste (1905) and The Red Mill (1906). But these weren’t set in fairyland. Herbert and MacDonough had previously attempted what many saw as a follow-up to Babes in Toyland in the fantastical operetta Wonderland (also 1905), but the critics made clear that technical problems and onerous length had killed the wonder by the time the show reached Broadway. Maybe Irish-born Victor Herbert saw Little Nemo as an opportunity at a musical mulligan?

For Nemo’s librettist, Abe Erlanger originally proposed George Hobart, a fellow member of the prestigious New York theater fraternity the Lambs Club, with whom Herbert had previously written a number of annual club revues. Hobart, too, seemed like an obvious choice: he had contributed lyrics to a Mother Goose for Klaw and Erlanger in 1903, but a disagreement over the booking of another Herbert–Hobart piece led to Hobart’s firing. Henry Blossom, with whom Herbert had written both Mlle. Modiste and The Red Mill, was tapped to replace Hobart, but Blossom, also a Lamb, refused the project out of loyalty to a fellow club member. Thus, before pen had even hit paper, the show was on the cusp of collapse—that is, until a producing partner suggested that Herbert collaborate with Harry B. Smith (author of, reputedly, more than 300 musical librettos), and Herbert’s librettist on his first popular success in the theater, The Wizard of the Nile (1895). Accordingly, Herbert and Smith began writing Little Nemo in earnest in the spring of 1908.

More or less simultaneously, Klaw and Erlanger took up the task of casting 20 or so principal and more than 150 ensemble roles. At the head of the company was to be “Master” Gabriel Weigel, a little person, reportedly “32-past” in years but only 2’9” in height. (The New York Times was quick to assure potential audiences that he bore “none of the grotesque unpleasantness of the average dwarf.”) Master Gabriel had become a minor celebrity two years earlier by playing the title role in Buster Brown, interestingly another Broadway property adapted from a comic strip (though in this case a non-musical). So convincingly did he play a child that the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children visited the New Amsterdam Theatre days after Little Nemo’s opening to investigate reported violations of the state’s child labor laws; society members relented only after they saw Master Gabriel shaving off a full beard backstage as he dressed for a performance.

More or less simultaneously, Klaw and Erlanger took up the task of casting 20 or so principal and more than 150 ensemble roles. At the head of the company was to be “Master” Gabriel Weigel, a little person, reportedly “32-past” in years but only 2’9” in height. (The New York Times was quick to assure potential audiences that he bore “none of the grotesque unpleasantness of the average dwarf.”) Master Gabriel had become a minor celebrity two years earlier by playing the title role in Buster Brown, interestingly another Broadway property adapted from a comic strip (though in this case a non-musical). So convincingly did he play a child that the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children visited the New Amsterdam Theatre days after Little Nemo’s opening to investigate reported violations of the state’s child labor laws; society members relented only after they saw Master Gabriel shaving off a full beard backstage as he dressed for a performance.

In another bit of trick casting, actress Florence Tempest, called by the Des Moines Daily News “America’s most lovable impersonator of boy parts,” was hired to play the featured role of the Candy Kid, the androgynous but ostensibly male role of Nemo’s guide from the waking world to Slumberland.

The real stars of Little Nemo, though, were to be a trio of comedians, in parts mostly superfluous to Nemo’s story. Joseph Cawthorn, a favorite “Dutch” comedian (who burlesqued German linguistic and cultural mannerisms), was cast to play Dr. Pill, the quack doctor of Slumberland’s royal court. Billy B. Van, the famous blackface minstrel, would play Nemo’s nemesis Flip, the cigar-smoking grump from McCay’s cartoons, in greenface. And Harry Kelly, a specialist in “eccentric” parts, was set to play the Dancing Missionary, a kind of early-twentieth-century homeopath, bent on convincing his potential converts that all worries disappear in the face of positive thinking. Though Little Nemo was officially billed as a “musical comedy,” these were character types straight off the variety stage. Likely in the spirit of providing “something for everyone,” Klaw and Erlanger’s extravaganza quickly became a strange and bloated mixture of theatrical styles, including the minstrel show, pantomime, operetta, farce-comedy, vaudeville, revue, and ballet, and the working-class buffoonery of Cawthorn, Van, and Kelly (prefiguring the delicious nonsense of the Marx Brothers) proved to be one of Little Nemo’s strongest box-office assets.

The real stars of Little Nemo, though, were to be a trio of comedians, in parts mostly superfluous to Nemo’s story. Joseph Cawthorn, a favorite “Dutch” comedian (who burlesqued German linguistic and cultural mannerisms), was cast to play Dr. Pill, the quack doctor of Slumberland’s royal court. Billy B. Van, the famous blackface minstrel, would play Nemo’s nemesis Flip, the cigar-smoking grump from McCay’s cartoons, in greenface. And Harry Kelly, a specialist in “eccentric” parts, was set to play the Dancing Missionary, a kind of early-twentieth-century homeopath, bent on convincing his potential converts that all worries disappear in the face of positive thinking. Though Little Nemo was officially billed as a “musical comedy,” these were character types straight off the variety stage. Likely in the spirit of providing “something for everyone,” Klaw and Erlanger’s extravaganza quickly became a strange and bloated mixture of theatrical styles, including the minstrel show, pantomime, operetta, farce-comedy, vaudeville, revue, and ballet, and the working-class buffoonery of Cawthorn, Van, and Kelly (prefiguring the delicious nonsense of the Marx Brothers) proved to be one of Little Nemo’s strongest box-office assets.

As the musical’s central conceit began taking shape—the mortal boy Nemo has been summoned by the Little Princess of Slumberland to be her own personal playmate—F. Richard Anderson began designing and overseeing the construction of the more than 1,000 costumes it called for. McCay’s drawings inspired ten elaborate scenic designs carried out by John Young and Ernest Albert, including such visual wonders as a “weather factory,” complete with projections (“vitagraph” displays) and fake explosions; an amusement park filled with practical carnival games set amid an island of cannibals; and the “Palace of Patriotism” (for the Act 2 finale, mentioned above) featuring a glockenspiel made of mini-Liberty Bells and a tableau vivant of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Musical director Max Hirschfeld assembled the orchestra of no fewer than 23 players—rehearsed personally by Mr. Herbert, advertisements proclaimed—and staging director Herbert Gresham began drilling the more than 200 singers, dancers, and comedians. (Incidentally, Little Nemo marked a return to dreamland at the New Amsterdam Theatre for the director and composer. The theater had opened in 1903, at the site on 42nd Street it still occupies today, with an inaugural production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream directed by Gresham, with Mendelssohn’s music arranged by Herbert.)

Klaw and Erlanger provided Winsor McCay an office-studio in the theater so that he could remain close to the rehearsals while keeping up with his rigorous drawing schedule and vaudeville appearances. By this time McCay had himself become somewhat of a vaudeville sensation in a “quick-draw” act, treating live audiences to a firsthand glimpse of his virtuosity with a pen. On the opening night of Little Nemo, the cartoonist had to dash out of the New Amsterdam at the end of Act 1 so that he might not be late for his entrance in the vaudeville show at William Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre just across the street. When Nemo toured, so did McCay, shadowing the musical’s route on William Morris’s vaudeville circuit, in effect cross-promoting the Little Nemo stage show. Additionally, McCay drew attention to the musical in his newspaper comics on November 15, 1908, January 17, 1909, and (appropriately, given the setting of Act 1, Scene 4) Valentine’s Day, 1909.

From the start, Little Nemo was an astounding critical success. Even McCay appears to have been surprised at how well things came together out of town in Philadelphia, writing in a telegram to the press, “Abraham Erlanger is a wizard . . . Wow!” The headline of the New York Times review affirmed the production “A Big Frolic / Glittering Spectacle with Plenty of Incidental Fun.” Though Little Nemo was undeniably wholesome entertainment, it was more than children’s theater; “it will take a grown-up sense of humor to get all the fun out of it,” the Times advised, especially the ceaseless punning and crackpot disquisitions of Cawthorn, Van, and Kelly, who “squeezed the laugh-making organs until there is not a squeak left.”

As might be expected, the reviewers lavished the bulk of their praise on the production’s awesome spectacle. The Boston Herald, in particular, effused:

The claims in advance have not exaggerated the facts. ‘Little Nemo’ is the greatest spectacle of the time. It recalls the tales of grandfather’s days when they used to fill the stage with girls and girls and more girls; when there were dazzling arrays of brightness; when Amazonian marches were in vogue, and when all sorts of grand transformation scenes kept the audiences amazed and bewildered.

(The paper didn’t seem to mind much that “The foundation of the play is almost nothing . . . .”) Similarly, Boston's Transcript reported that Little Nemo’s delights were at least as wondrous as the storied hits of a generation ago, but lauded how modern machinery made the production’s scenic marvels all the richer. As such, Little Nemo was dually embraced as a nostalgic throwback to the fondly recalled but creaky burlesques of the nineteenth century and a triumph of the enlightened present day, in its reliance both on the most up-to-date stage technologies and relentless topical humor (which today require lengthy explanations; I have provided the script more than 100 explanatory footnotes). “[T]he result,” the paper wrote, “justifies the time and money that have surely been expended to make ‘Little Nemo’ a wonder of stagecraft.”

As for the music, the Transcript warned that the score contained “not many airs that will be whistled by the street boys”—and the Boston Herald counted the play’s music as its third principal attraction, after its scenery and jokes. At the beginning of the project, Victor Herbert was greatly excited by the subject matter, telling the Pittsburgh Gazette in June 1908, presumably in the thick of composing:

The idea appeals to me tremendously. It gives opportunities for fanciful incidents and for “color.” It’s all in Dreamland, you know, and that gives great scope for effects, the writing of which appeals to me immensely. Besides, there is an excellent story—the love between Nemo and the Princess—and there are chances for humor, too. I can only say that I will approach my part of the task with enthusiasm and I hope to furnish an interesting musical setting.

After the fact, however, Herbert lamented the absence of a serious adult romance, an opportunity to infuse substantive emotion into his writing. Without one, he feared his score was merely a string of novelty tunes and production numbers that sounded all too much alike. The New York Times offered Herbert’s music faint praise, calling it “pleasant,” “though . . . it serves its purpose well.” But it was not without lasting legacy of sorts; a six-year-old Richard Rodgers was taken to see Little Nemo, and he remembered fondly “Give Us a Fleet” and “Will You Be My Valentine?” No doubt these served as grist for the mill for a theater composer who went on to write quite a few patriotic tunes, and more than a few playful courtship songs.

Little Nemo played 123 or 111 performances (counts differ) in New York before embarking on an extended tour through the Northeast, the Midwest, and the South. McCay took his son Bobby, thought to be the real-life model for the Nemo character, on the tour’s first leg, dressing him up like the little protagonist and installing him on a prop throne in theater lobbies as an additional marketing gimmick.

The original capital outlay for Little Nemo was only about $86,000, a small fraction shy of the outrageous sum the producers originally announced. But the show cost $20,000 a week to run, which required sold-out houses at the New Amsterdam’s top ticket price of $1.50 (about $40 in today’s money) in order to just break even. Though it was running a deficit, the show could not afford to close—in a situation that, theater scholar Mark Cosdon has pointed out, neatly parallels the more recent financial woes of Broadway’s Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark (2011). The spectacle was also terrifically expensive to tour, employing a custom 17-car train, the Little Nemo Special, to transport the enormous company and all its scenery from stop to stop. On top of this, Herbert, a serious musician, insisted on an uncustomary, unsustainably high minimum number of orchestra players in large cities, even when ticket sales waned, depleting coffers even further.

When the celebrated production finally shuttered to a deep financial loss in 1910, Winsor McCay perceived the entire outing as a failure and took the disappointment personally. Perhaps seeking a clean break with the American stage, he petitioned his editors at the New York Herald for leave to take his vaudeville act to Europe, a proposal they ultimately rejected. These events coincide with a cynical shift in tone in his Little Nemo comics, and likely encouraged him to redirect his energies toward flipbook animation and, later, to animated films. His first such film was, in fact, Little Nemo (1911), followed quickly by How a Mosquito Operates (1912) and Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), sometimes looked to as the earliest examples of animated cartoons. The last Nemo strip McCay drew for a long time was published by William Randolph Hearst’s New York American on July 26, 1914. (McCay continued the boy’s adventures for a short stint in the mid-1920s).

Though Nemo has largely faded from the American memory (and, as Cosdon has observed, the very name Nemo has been irrevocably poached by a little Pixar clownfish), occasionally still he surfaces. An animated feature styled Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, released in the U.S. and Japan in 1989, precipitated a video game for the original Nintendo NES home-gaming console called Little Nemo: The Dream-Master (representing an iconic moment in my own childhood video-gaming)—both of which retain some small cultural currency today. An opera for young people also called Little Nemo in Slumberland, bearing no relation to the 1908 stage show, with a libretto by J.D. McClatchy and music by Daron Hagen, premiered at the Sarasota Opera in 2012. And just last December, German art book publisher Taschen issued a complete, two-volume large-format set of all of McCay’s original drawings in full color (ISBN 978-3836545112). This Taschen release may be the best point of access we have for understanding the energy of Herbert and Smith’s weird theatrical enterprise.

But for the intrepid reader, the accompanying libretto, transcribed and annotated painstakingly from a surviving typescript presents the original vision for the 1908 musical extravaganza that—despite its budgetary blunders—was an undisputed jewel of its age’s stages. On its own, the text is nothing short of perplexing. Its structural incoherence and lack of dramatic thrust make it a wonder to the contemporary reader that the musical ever could have been as popular and as well-received as it was. It is extraordinary in its refusal to tether the action to a central spine, forgetting what should be central plot points as soon as it establishes them. (A New York review acknowledged that “The ‘book’ of the second and third acts does not keep the promise of the libretto of the first.” That Nemo is needed to recover King Morpheus’s missing elixir of youth, for example, is never again mentioned after the first scene. Perhaps Smith sought absolution for such narrative hiccups by providing Flip the ham-handed realization at the start of Act 2 “Holy smoke! I’ve lost the plot! The plot! Where is it?”) The structure’s an unmitigated mess, yet there’s an undeniable, if totally mystifying, energy or sublimity about it all.

Mark N. Grant has described early musical books as “Infantile Dada,” and—if the politics of dada are removed from the discussion—that might not be too bold a characterization of Harry B. Smith’s work on Little Nemo. (The scenes set on the cannibal island, in particular, bear an uncanny resemblance to Raymond Roussel’s Impressions of Africa, a pre-surrealist dada-esque exercise dramatized for the avant-garde Paris stage in 1912.) When Little Nemo is strange, it is very strange: the beer-drinking male cat named Gladys; the dance of the marionette baby dolls in their cribs; the chorus of anthropomorphic typewriters and typewriter desks; the cannibal king’s magical “bamboozle bush” that can breathe life into inanimate objects; the song about teaching a Teddy bear to dance; the sudden decision to host a full-fledged Olympic Games in the middle of a savage wilderness; Captain Grouch’s self-destruct “electric kazazas” button; the announcement, then immediate cancelation, of a Zouave military march. Certain oddities, like the woman-hating hypnotist pirate cook, would be more at home in a Strindberg play (compare her with the vampire cook of Strindberg’s The Ghost Sonata, which premiered in Stockholm the same year) than in the typical Broadway musical-comedy fare of 1908. A reader today might seriously wonder if Smith had any plan in mind as he set to work, or if he merely let his imagination drift from one crazy idea to the next, committing each to the page with the same nondiscriminating gusto. The surrealists would adopt a similar technique decades later (indeed, deliberate experimenting and overambitious showmanship can sometimes be but a short step apart), but, in the wake of World War I, the surrealists’ was a different world. They were also not trying to yield returns on a $100,000 investment.

Little Nemo’s narrative scatteredness pushes patience to the brink, but the consequent brain-scramble is somehow more charming than annoying. The untiring parade of nonsense atop nonsense creates a kind of self-sustaining dramaturgical engine fueled by its own spontaneity. (The Boston Herald articulated this sense: “the surprises in scene or situation follow one another like flashes of light.”) One result is that Little Nemo feels more like a thematic musical revue than a narrative musical play. Smith was actually just finishing his work on the Ziegfeld Follies of 1908 when he turned to Nemo. Given the disjointedness of the libretto, the score can hardly be faulted for failing to jell into a single, cohesive theatrical dessert. While it is probably true that Herbert’s 30-some sugary tunes bear the indelible stamp of an earlier time and folksier theatrical sensibility, the sheer diversity they demonstrate despite a common palette of mostly bright major keys is itself testament to Herbert’s musical and dramatic ingenuity. (A 1909 recording of the Victor Herbert Orchestra playing a medley from Little Nemo provides a tantalizing auditory scrap of the pep and punch of the score’s original orchestral rendering.)

If the musical arrives at a happy end, it does not earn it. Like the sumptuous, expensive court spectacles of seventeenth-century Europe, Little Nemo ends only because a quota of fun has been had, the night is over, and it is time to sleep—or, rather, it is time to put the theatrical dreams to bed, so that the appreciative spectators might retire to their own. Only after a six-part “Dream Ballet” finale, though, perhaps the first on the American musical stage, predating the end-of-act dream ballet in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! by almost 35 years. Could the memory of Nemo have helped Rodgers to help Laurey, in that musical, to make up her mind?”

In its ceaseless efforts to please, Little Nemo is a celebration of many things: unbridled American imagination, unbridled American capitalism, unbridled American imperialism . . . As for the last, perhaps Herbert sensed something a little too prescient in Smith’s lyric

I wish there’d be a war.

I love the cannon’s roar.

It must be like the Fourth—I bet it is.

and decided to leave that song untouched; no music for “When Nemo is the Captain of the Regiment” survives. In less than a decade’s time, Nemo’s wish would come true, and if he had been an actual boy, his adventures then in far-off lands would surely have borne no resemblance to the “Happy Land of Once-Upon-a-Time” cooked up for him by Klaw and Erlanger, by Smith and Herbert in the sweet innocence of the first decade of a new century. (Were Nemo to have survived the war, what a surrealist he surely would have grown to be!) But Little Nemo is also a celebration of childhood, a time when such serious, real-world thoughts should still be a long way off. It is a time to try many things, sometimes too many things, and not to fear underperforming or failing at them altogether. It is a time when $100,000 sounds like imaginary money, so why not spend it to the fullest? After all, the longer the fantasy, the dream, keeps going, the longer we can stave off the inevitability of growing—or waking—up.

A Note on the Libretto

The surviving typescript is surely a pre-Broadway working draft, as it is excessively long; a number of songs appear that are not listed in show programs and were not published in the 1908 piano-vocal score (though Herbert’s musical doodlings for some of these numbers are on file in the Library of Congress); the scene aboard Captain Grouch’s pirate ship is not listed in show programs; and the song “They Were Irish,” added on tour in Boston, is nowhere to be found. If everything Harry B. Smith calls for this libretto was not realized in production—material was certainly cut and reshuffled in rehearsals—at least most of it was, as it is scripted here.

All explanatory and editorial footnotes are mine. Surely these only scratch the surface.

Thanks to Lewis Bramlett’s New Amsterdam Theatre website for archival materials (including the production photos shared here), and to Jennifer L. Shaw for research and editorial assistance.

Download the libretto as:

Note: The title used in the eBook is Little Nemo in Slumberland, reflecting the title used in the source text for the edition. However, the original programs and news reports list the title simply as Little Nemo.

Further Reading

Additional information on the writing and production of Little Nemo can be found in:

Canemaker, John. “Little Nemo on Broadway” (ch. 7) in Winsor McCay: His Life and Art (expanded ed.). New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2005. 140–153.

Gould, Neil. Victor Herbert: A Theatrical Life. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008. 386–389.

Waters, Edward N. Victor Herbert: A Life in Music. New York: Macmillin, 1955. 321–326.

Musical Links

The songs in the accompanying libretto marked with a music note symbol can be heard in MIDI audio format on Colin M. Johnson’s excellent website Victorian and Edwardian Musical Shows. Visit his Little Nemo page at http://www.halhkmusic.com/nemo.html.

Most of the score has also been recorded (with a two-piano instrumentation) by the Michigan-based Comic Opera Guild. CDs and MP3s of Little Nemo are available for purchase from them at http://www.comicoperaguild.org/PAGES/RECORDINGS.html.

About the Editor/Writer

Brian D. Valencia is Lecturer of Dramaturgy, Theory, and Criticism in the Department of Theatre Arts at the University of Miami and a doctor of fine arts candidate at the Yale School of Drama. As a composer, lyricist, musical director, dramaturg, and performer, Brian has collaborated on numerous theatrical works seen and heard in New York City; Washington, D.C.; Miami; New Haven, Connecticut; and Seoul, South Korea. His scholarly writing has appeared in Contemporary Theatre Review, Common-place, Theater magazine, The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy, and a forthcoming volume by Palgrave academic press. He holds master of fine arts degrees from the Yale School of Drama and New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. Brian has taught at Yale, Florida International University, and Miami’s New World School of the Arts. He lives and works in South Florida.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Collections

Submitted by Sean Martin (not verified) on September 14, 2015 - 5:09pm

Little Nemo article

Submitted by unoclay (not verified) on November 29, 2016 - 11:41am