Biblio File

Madame Bovary's Cultural Mark

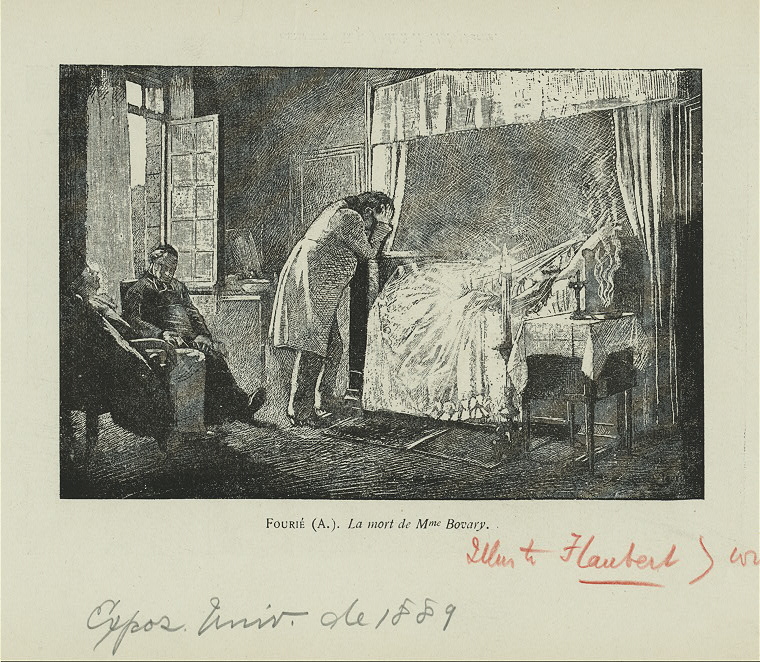

Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary was more than just an exciting novel, it set a standard for novels, and created a buzzword about having a glamorized, exaggerated conception about oneself. The novel first appeared in serial form in 1857, and the morality of the tale quickly entered into public debate. Flaubert persevered, and the work became a classic. A few years ago, some 4,500 omitted pages that Flaubert originally penned were released online, in the original French, at bovary.fr.

In 1934, T.S. Eliot added the -ism suffix to Emma's last name and coined a new word. In Essays, he wrote: "I do not believe that any writer has ever exposed this bovarysme, the human will to see things as they are not, more clearly than Shakespeare."

Modern writers and artists have put their spin on Bovarism. Mario Vargas Llosa's The Bad Girl has Charles Bovary in the form of the character of Ricardo. (Fun fact: The Bad Girl was reported to be one of Madonna's favorite books.) Authors Raymond Carney and Leonard Quart mentioned it in their nonfiction book The Films of Mike Leigh as "'talking-to-hear-yourself-talk' to impress yourself and your listener with a depth of feeling and thought that doesn't refer to anything outside itself." Publisher's Weekly suggested that Emma Bovary is the "feminine incarnation of Don Quixote de la Mancha: he lost his mind reading novels of chivalry while she lost hers reading romance novels" and then things get even more muddled in their review of Julian Barnes's Flaubert's Parrot in their article "10 Books Based on Other Books." Barnes also writes about the statue of Flaubert in Rouen, France, which, although not the original statue, bears testament to the passage of time. NYPL's digital collection has a few images of the statue.

Author A.S. Byatt calls Madame Bovary "the least romantic book I have ever read."

Author Julie Kavanagh examines the portrayals of Emma Bovary, including one based on the graphic novel Gemma Bovery.

There have been a few film interpretations of Madame Bovary and a 2014 version directed by Sophie Barthes. There's also a 2014 film of Gemma Bovery, with this tidbit of trivia.

Perhaps the most recent reinterpretation of Madame Bovary is Hausfrau by Jill Alexander Essbaum. The main character, Anna Benz, toys with adultery in an attempt to compensate for the sadness in her life, belying her suburban dream life in Zurich with her banker husband and three children. Anna's character owes no small debt to Bovarism, but the interspersed vignettes with her therapist start to feel tiresome after a while. However, Essbaum's writing is deft and the tale does move along well.

Perhaps the most recent reinterpretation of Madame Bovary is Hausfrau by Jill Alexander Essbaum. The main character, Anna Benz, toys with adultery in an attempt to compensate for the sadness in her life, belying her suburban dream life in Zurich with her banker husband and three children. Anna's character owes no small debt to Bovarism, but the interspersed vignettes with her therapist start to feel tiresome after a while. However, Essbaum's writing is deft and the tale does move along well.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Bovarism as a Reader's Right

Submitted by Elizabeth (not verified) on June 24, 2015 - 1:54pm

neat comment!

Submitted by Jenny (not verified) on June 24, 2015 - 5:49pm