Where Did Times New Roman Come From?

Top: Gros Cicero, from Surius’ Commentarivs Brevis Rervm In Orbe Gestarvm. Middle: Plantin, from H.G. Wells’ Tono-Bungay. Bottom: Times New Roman, from The Monotype Recorder, Vol. 21.

If you open up your word processing software and start typing, chances are you’re looking at Times New Roman. It’s so ubiquitous that we take it for granted, but just like Spider-Man or Wolverine, this super-typeface has its own origin story.

You might be surprised to learn that Times New Roman began as a challenge, when esteemed type designer Stanley Morison criticized London’s newspaper The Times for being out-of-touch with modern typographical trends. So The Times asked him to create something better. Morison enlisted the help of draftsman Victor Lardent and began conceptualizing a new typeface with two goals in mind: efficiency—maximizing the amount of type that would fit on a line and thus on a page—and readability. Morison wanted any printing in his typeface to be economical, a necessity in the newspaper business, but he also wanted the process of reading to be easy on the eye.

Morison looked to classical type designs for inspiration. He liked the look of the modern typeface Plantin, which was based on the older typeface Gros Cicero, designed by Robert Granjon. The “cicero” in Gros Cicero was a contemporary term for the size of the type—today, we would describe cicero’s size as 11.5-point—and the “gros” referred to the proportions of the letters. The Rare Book Division has an example of Gros Cicero in Surius’ Commentarivs Brevis Rervm In Orbe Gestarvm, printed in 1574.

To achieve efficiency, Morison raised what is called the “x-height” of the letters. This is the distance between the top and bottom of a lower-case letter without ascending or descending parts, like a, c, or m. This is easier to illustrate than describe, so check out this handy diagram:

He also reduced the “tracking,” or spacing between each letter, to make a more condensed typeface. As you might imagine, moving letters closer together could also make them harder to read. To protect his second goal of readability, Morison had to alter the shape of the letterforms. The thicker portions of each letter—for example, the vertical lines of the “n” above—were widened, so that the letters held more ink and appeared darker when printed, which contrasted more clearly against the paper. The intersections of these thicker strokes were thinned; for example, where the vertical lines of the “n” meet its serifs. This kept the shape of the letters from becoming muddled and also gave them a rounder, more legible look. All of these differences can be clearly seen in a comparison of the old typeface with Morison and Lardent’s new creation, which The Times published in a pamphlet around the time of the change.

The Times tested its type thoroughly. In 1926, the British Medical Research Council had published a Report on the Legibility of Print, and the new typeface followed its recommendations. Before final approval, test pages were also submitted to a “distinguished ophthalmic authority,” (Morison, vol. 21, no. 247, p. 14) leading The Times to announce that its typeface had “the approval of the most eminent medical opinion.” The newspaper recognized that scientific analysis was well and good, but an equally important test was actually reading it. Members of the team practiced reading for long periods of time, under both natural and artificial light. After test upon test and proof upon proof, the final design was approved, and “The Times New Roman” was born.

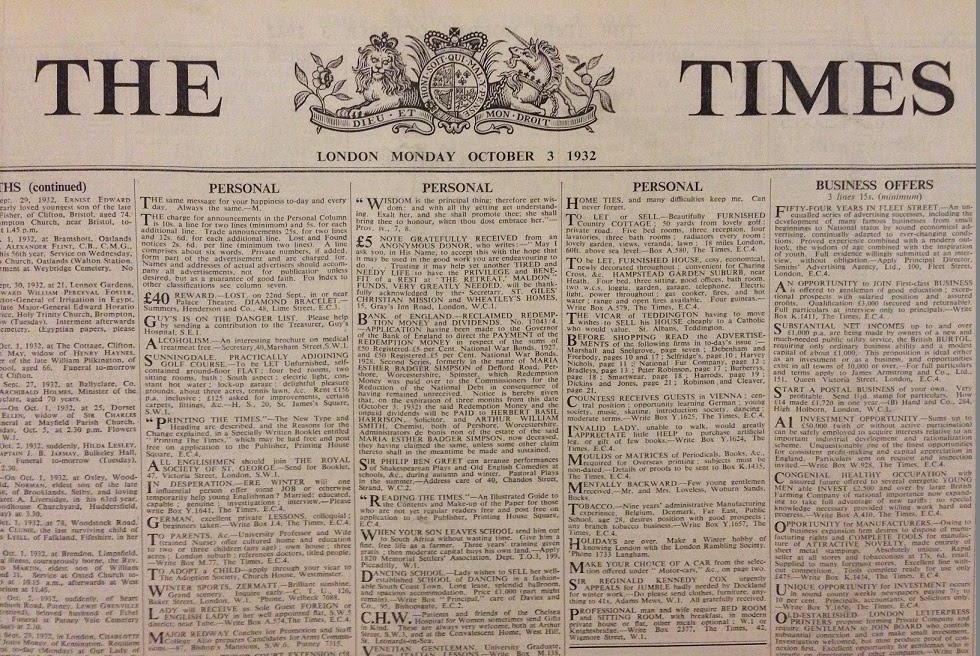

On October 3, 1932, The Times unveiled its new typeface with great fanfare. “From September 26th to October 3rd,” notes The Monotype Recorder, “all the readers of The Times were reminded, daily, of the importance of type and printing.” It was the first time that a newspaper had designed its own typeface, and The Times owned its exclusive rights for one year. In the following years, American publishers were slow to adopt Times New Roman because in order to look its best, it required an amount of ink and quality of paper that American newspapers were initially unwilling to shell out for. It eventually caught on as a typeface for books and magazines, with its first big American client being Woman’s Home Companion in December 1941. The Chicago Sun-Times began printing with it in 1953.

An interesting footnote to the development of Times New Roman trickles down to us in the present day. The original hardware for the typeface—the “punches” that helped create the molds for casting type—were created jointly by the Monotype Corporation and the Linotype Company, the two main manufacturers of automated typesetting machines and equipment at that time. Both companies subsequently made sets of the type for purchase. Monotype named its type “Times New Roman,” while Linotype used “Times Roman.” Fast forward to the computer era: when selecting “fonts” for their word processing programs, Apple chose to license the Linotype catalog, and Microsoft licensed Monotype’s. That’s why the name of this typeface is slightly different depending on your choice of Mac or PC!

In 1932, The Times specifically noted that their new typeface was not intended for books: “It is a newspaper type—and hardly a book type—for it is strictly appointed for use in short lines—i.e., in columns.” They later developed a wider version adapted to fit a book’s longer lines of text. This idea that the use of a typeface affects its form struck me as very relevant to today’s world of e-book publishing and web-based content. Indeed, Times New Roman’s chief competitors these days are Arial and Calibri, two typefaces whose lack of serifs makes them easier to read on a screen, according to many. But at 82 years old, Times New Roman is still going strong and proving that our humblest word processing friends have some pretty historic beginnings.

If you’re taken with typography, then NYPL has a mountain of resources for you. For starters, try Alexander Lawson’s Anatomy of a Typeface, Stanley Morison’s A Tally of Types, or Daniel Updike’s Printing Types: Their History, Forms, and Use.

“Sphinx” diagram courtesy Wikimedia Commons. All other images: Rare Book Division and General Research Division. New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, Tilden Foundations.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Times New Roman

Submitted by Mike Lindgren (not verified) on December 12, 2014 - 2:25pm

Times New Roman

Submitted by David Blake (not verified) on August 21, 2021 - 11:23pm

Times New Roman

Submitted by Robert Fitzpatrick (not verified) on December 13, 2014 - 6:25pm

NYPL font

Submitted by Jaylyn Olivo (not verified) on December 16, 2014 - 2:54pm

NYPL font

Submitted by Morgan Holzer on December 17, 2014 - 1:50pm

Thank you...

Submitted by Oisín (not verified) on December 19, 2014 - 10:47am

Times New Roman

Submitted by :Donna (not verified) on December 26, 2014 - 12:26pm

Me too! That's why my

Submitted by Melissa S. (not verified) on December 27, 2014 - 2:28pm

The defaults are changing

Submitted by Kevin Menzel (not verified) on December 27, 2014 - 1:53am

Some more to the story

Submitted by Jeff Potter (not verified) on December 30, 2014 - 4:38pm

Thanks Jeff. If you hit a

Submitted by Lauren Lampasone on December 30, 2014 - 4:54pm

Fontificating

Submitted by Granite Sentry (not verified) on January 6, 2015 - 10:47pm

Much more to this story

Submitted by Sumner Stone (not verified) on March 13, 2015 - 12:08pm

Thank you for sharing this

Submitted by Meredith Mann (not verified) on March 14, 2015 - 12:35pm