24 Frames per Second

Mike Nichols, 1931-2014

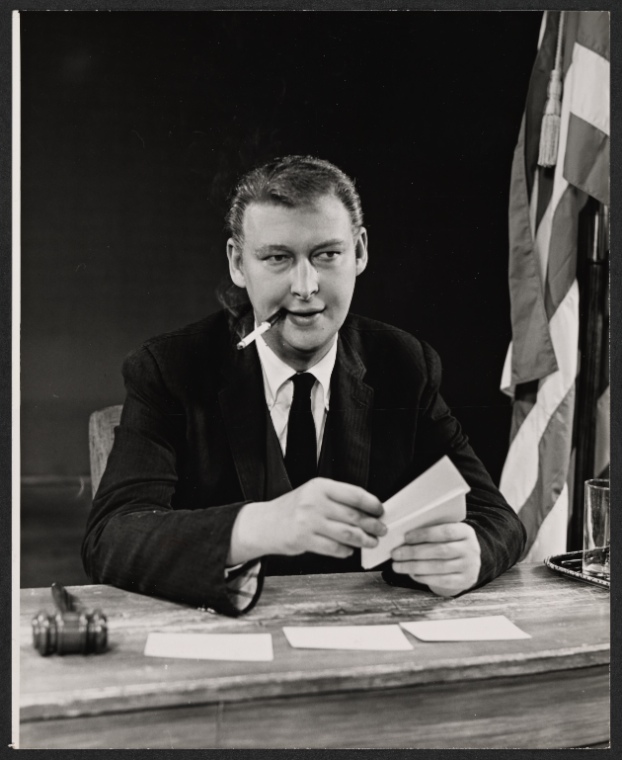

Mike Nichols, the revered film and theater director who is one of only a dozen EGOTs (winners of Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, and Tony Awards), died of a heart attack yesterday at age 83.

Still best remembered for the one-two punch of his first two films, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Graduate—both key early indicators of the new, adult direction that American cinema would take over the following decade—Nichols had already won two of an eventual seven Tony Awards for directing before he stepped behind a camera. Indeed, for the whole of his career, Nichols alternated between work of equal significance on stage and on film, a feat achieved to the same extent by only one other American director, Elia Kazan.

Nichols’ first Tony was also his first directing effort: Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park, a flailing 1963 production that Nichols rescued in summer stock. Simon wasn’t convinced the play would work until he heard the first laughs from the audience. “In the first fifteen minutes of the first day's rehearsal I understood that this was my job, this was what I had been preparing to do without knowing it. It had literally not crossed my mind as far as I was aware,” Nichols later said. “I felt what I had never felt performing: I felt happy and confident and I knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

Prior to that, Nichols had been mainly a performer—a disc jockey for a classical radio station and a member of Paul Sills’ Chicago-based improv troupe the Compass Players (a forerunner of the Second City). From there grew his legendary partnership with the comedienne Elaine May; together, they performed their saucy, literate comedy routines in Manhattan nightclubs, on live television, and finally in a Broadway showcase, directed by Arthur Penn, which ran during the 1960-61 season. Shortly thereafter the pair broke up, explosively, and Nichols was cast adrift—until the producer Saint-Subber thought of him for Nobody Loves Me, the title of which was soon changed to Barefoot in the Park.

The Graduate (which preceded Nichols’ searing version of Virginia Woolf in development) was one of the great calling card movies. It was innovative both visually, with its iconic images of Dustin Hoffman at the bottom of a swimming pool, floating on an LAX people mover, and framed in the arch of Anne Bancroft’s leg, and aurally; the editing-room temp track of Simon and Garfunkel songs evolved into one of the cinema’s first pop music scores. Kazan attended an early screening of The Graduate and wondered aloud if Mrs. Robinson was a “worthy antagonist.” “I think he had a different relationship to women than I did,” Nichols said later. He won an Oscar for directing the film.

And yet Nichols did not join the New Hollywood generation that included Robert Altman and Martin Scorsese; rather, like Kazan, he became known mainly as a skilled and sought-after directors with a catholic and rather mainstream taste in material. After the failure of the underrated Warren Beatty-Jack Nicholson comedy The Fortune, Nichols reinvented himself as a theatrical producer, godfathering the six-year hit Annie into existence and discovering Whoopi Goldberg. And he continued to direct important plays, including the original Broadway productions of Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing and David Rabe’s Hurlyburly. Eventually he returned to film, making Silkwood, The Birdcage, and Primary Colors. Nichols also directed acclaimed adaptations of the plays Wit and Angels in America for HBO; a New York Shakespeare Festival production of The Seagull, headlining Meryl Streep; and swan-song revivals of Death of a Salesman (Nichols’ final Tony, in 2012) and Harold Pinter’s Betrayal, which closed earlier this year. A major presence in Nichols’ late work—a star of both The Seagull and Death of a Salesman, as well as Nichols’ final film, Charlie Wilson’s War—was the late Philip Seymour Hoffman.

One of Nichols’ great innovations in The Graduate was to cast Dustin Hoffman—short, nondescript, obviously Jewish—in a role written as a WASPy Robert Redford type (“a walking surfboard,” in Hoffman’s words). Nichols himself was something of an inversion of that contrast—tall, blonde, and legendarily articulate and urbane, he was nonetheless a refugee from Hitler, a German-born Jew who came to the United States at the age of 8. His hair fell out due to a whooping cough shot, his father died when he was 12, and the only English phrases Nichols (then known as Mikhail Igor Peschkowsky—Igor to his schoolmates) knew upon arriving in America were “I do not speak English” and “Please, do not kiss me.” Often approaching his early work as a sardonic outsider-observer, Nichols matured into a role as the ultimate Broadway insider, a reluctant interviewee but a legendary raconteur for lucky initimates. “Sometimes I feel I should be paying admission,” said Diane Sawyer, his wife.

“What is it really like?” is the one idea Nichols returned to again and again when he could be coaxed into interviews. In 2004, he expanded on how that basic notion informed all his work:

I think I have always been interested in one main question in making a film or doing a play: What is this really like? Not, what is the convention? Or, what is the agreed-upon approach here? But, what is this moment, this emotion, this action, this experience like when it happens in life? In order to try to answer that question, sometimes we have to leave reality behind and try to go where the poetry goes. But the question is always the same.

Rare recordings of many of Nichols’ theatrical productions can be viewed on-site at the Library for the Performing Arts’ Theatre on Film and Tape Archive, including The Gin Game, Annie, Waiting For Godot (with Robin Williams), The Seagull, Monty Python's Spamalot, Death of a Salesman, and Betrayal.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

mike nichols

Submitted by missumuch (not verified) on November 20, 2014 - 8:50pm

Mike Nichols

Submitted by Tim (not verified) on November 21, 2014 - 12:29pm

my condolences are extended

Submitted by john m tossas (not verified) on November 21, 2014 - 12:48pm