Archives

The Battle of Antietam in Maps: An Interview with Researcher Jamesina Thatcher

In 2013, Jamesina Elizabeth Thatcher received a scholarship award from the Save Historic Antietam Foundation (SHAF), a non-profit battlefield preservation organization. Preservation efforts began at Antietam Battlefield in Maryland in the late nineteenth century with the work of the Antietam Battlefield Board and Ezra Carman. Carman commanded the 13th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry at the battle, and became a member of the Battlefield Board in the 1890s. Early efforts to commemorate the area resulted in map-making, which were published with historical inaccuracies. Carman continued to source new personal testimonies from soldiers at the battle in order to create a more perfect map until his death in 1909.

Building upon her academic background in military history and geography (and general love of maps), Thatcher's project at SHAF revisits Ezra Carman's efforts a century later. Reconnecting the veterans' testimonies with physical structures and topography of the battlefield, Thatcher improved the understanding of troop movements during this important Civil War clash. Recently, I spoke with Thatcher about her project and the use of archival resources, including the Ezra A. Carman papers here in the Manuscripts and Archives Division. We discussed Antietam's importance as a Civil War battle, ongoing efforts to preserve the site, and her methodology of using historic testimonies to ascribe GPS coordinates on the battlefield. Thatcher's work is an interesting example of how archives inform our historical knowledge of environments.

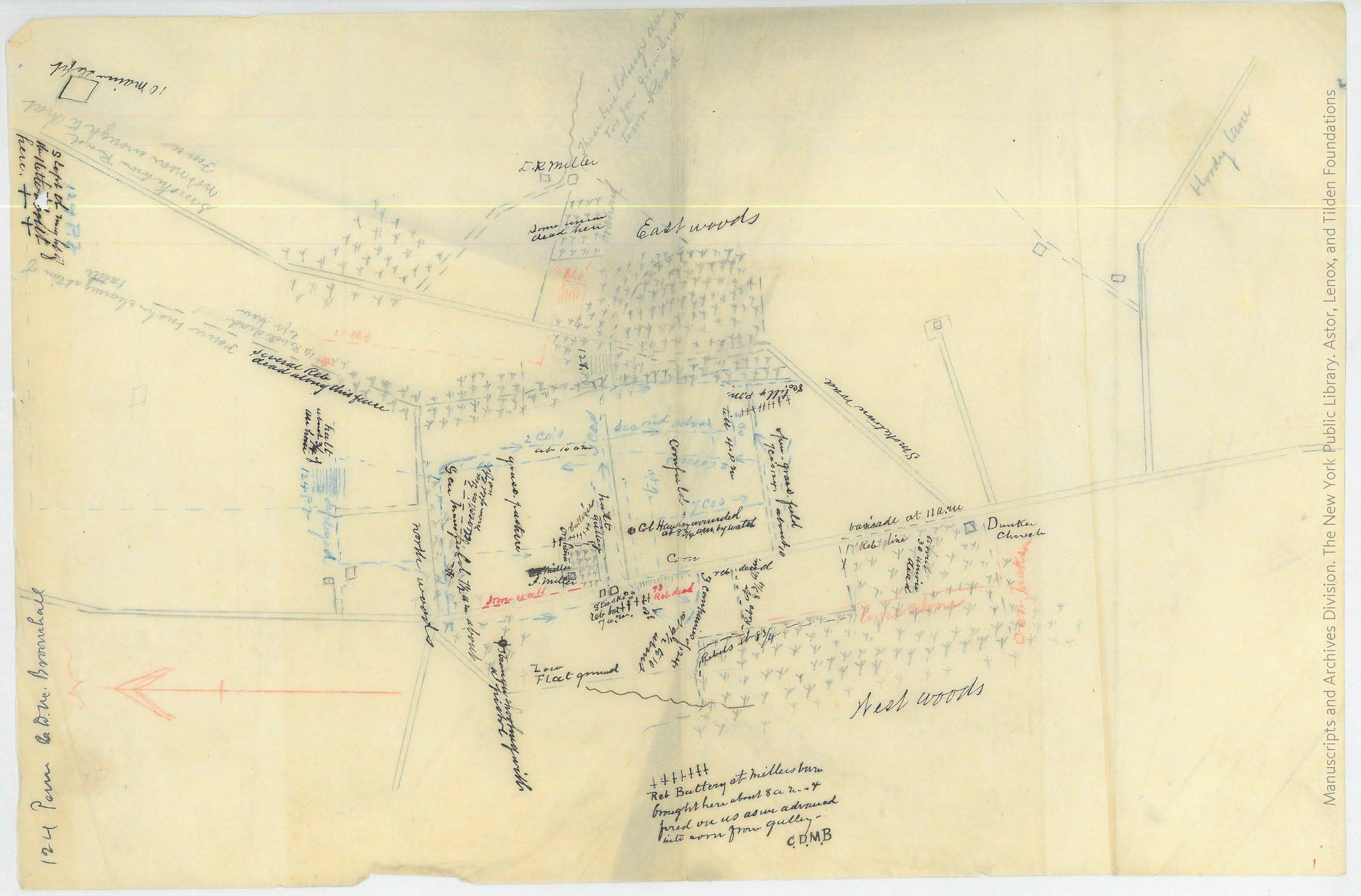

Illustration included in a letter by veteran Sylvester Byrne, 1895

Illustration included in a letter by veteran Sylvester Byrne, 1895

Can you begin by giving a brief summary of the Maryland Campaign?

The 1862 Maryland Campaign was the first Confederate invasion of the North by General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee had won a string of recent stunning victories and wanted to keep the momentum flowing. On September 3rd, Lee wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis that this was the best time to enter Maryland and reasoned that this offensive would secure Southern independence, influence Northern fall midterm elections, provide the opportunity to obtain supplies while allowing Virginia a rest, and liberate Maryland from the Union.

As Lee made his way through Maryland, Union Major General George B. McClellan and the Army of the Potomac set out from Washington, D.C. to stop him. On September 14th, battles raged at South Mountain and Harpers Ferry. Although South Mountain was a decisive Union victory, Harpers Ferry surrendered to the Confederates on September 15th thus causing Lee to make a stand at Antietam. On September 17th, the battle began at dawn and lasted for nearly twelve hours. Battered and bruised but not broken, both sides held their lines and the battle resulted in 23,000 casualties. During the night of September 18th, Lee crossed the Potomac back into Virginia. On September 19th & 20th, the last engagement, the battle of Shepherdstown, occurred and essentially wrapped up Lee's campaign.

Although not a clear victory, Antietam provided Lincoln with the opportunity to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22nd. This changed the war's objective from not only preserving the Union but to end slavery as well.

Battlefield mapmaking in the 1890s occurred at a particular moment in history, only a few years after the Century Company published its popular Battles and leaders of the Civil War. At the same time as the Antietam Board was active, similar maps were being created for the Battle of Gettysburg. Can you provide insight as to why the 1890s were a prosperous time for battlefield preservation?

In the 1890s, conservation became popular for three reasons: It coincided with the Reconciliation Era for Civil War veterans; the Spanish-American War influenced all Americans to band together and commemorate the Civil War; and Congress created national battlefields through the War Department such as Chickamauga & Chattanooga (1890), Shiloh (1894), Gettysburg (1895), Vicksburg (1899). Antietam had been marked to become a national military park in 1890 but never became one, instead it was designated a national battlefield.

Despite its name recognition, Gettysburg is less researched than Antietam. Antietam has several resources, such as Carman's The Maryland Campaign of 1862 (refered to as the "Carman Manuscript," the original is in the Library of Congress's Ezra Ayers Carman papers, however first published in 2008) and the Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam. Although Gettysburg has John B. Batchelder's guidebook and three detailed maps depicting three days of fighting, Carman's Atlas contains fourteen maps, some in fifteen minute intervals for one day of fighting. For whatever reason, and so many reasons are debatable, Gettysburg has always overshadowed Antietam.

How did Carman contribute to the marking of the battlefield?

Carman fought at Antietam with the 13th NJ and had a real connection with that battle. He remained in contact with veterans on both sides for years after the battle attempting to collect their recollections through correspondence so that he could write a history of the battle. He was appointed Historical Expert to the Antietam Board in 1894 and the volume of correspondence increased dramatically. In these letters, veterans informed Carman where their regiment was located, what enemy regiment was faced, what terrain features were in the area, and any other pertinent information. Some vets made markings on maps Carman sent to them. Other vets drew maps and sent them back to Carman. On occasion, State delegation, officers, and veterans visited the field to help Carman mark the troop placement correctly.

Luckily for Carman, George W. Davis was appointed President of the Board at the same time in 1894 which allowed for Carman to get his hands into everything that made returning the battlefield to its state in 1862. Davis fully supported Carman and took care of all administrative matters while Carman worked on the field itself.

Printed map with hand-drawn corrections, with references to letters submitted by veteransAnd then he published the Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam with errors.

Printed map with hand-drawn corrections, with references to letters submitted by veteransAnd then he published the Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam with errors.

Carman released the first Atlas in 1904. Colonel Emmor B. Cope's base map was completed in 1898 and Carman used Cope's map to plot the troop positions on. Unlike the earlier maps made by the Antietam Board in 1893 & 1894 by John C. Stearns & Henry Heth, Cope's map was accurate. However, some of the information Carman received over the years as to where troops were located was inaccurate because he had sent the vets cut-outs of the early inaccurate maps. These errors appeared on the 1904 Atlas and within weeks of releasing 1000 copies, Carman was receiving letters from the vets asking him to make corrections. Over the next four years, Carman did make dozens of corrections based on the letters and hand-drawn maps of vets. He re-released another 1000 copies of his Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam in 1908. Very few letters appear in any files finding error with this Atlas and it is considered the definitive study along with his Manuscript. No other other change was made by Carman after the 1908 release because he died on Christmas the following year, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on New Year's Eve.

One very important thing to be recognized about Carman and the Atlas, is that he worked on it from 1898-1908 for free. Congress did approve appropriations for Carman to finish the Atlas so he took it upon himself to plot troop positions in his spare time as he worked as a War Clerk.

Since the last Atlas was published, have significant changes occurred in the site?

There have been numerous changes to the battlefield over the years. Probably, the most damaging was the construction of Route 65 in the 1950s through the West Woods. Although a person can still get a feel for the action that occurred in the West Woods, that road really throws a wrench in the picture. The Middle Bridge was knocked out by the Johnstown Flood in 1889 and thus looks different from the Upper and Lower Bridges. The vast majority of farmsteads are still there but modern houses have been constructed on the field and are terrible eyesores. A large portion of the East Woods was lost and is now being replanted. The tower at Sunken Lane was built in 1896 and is a blessing and curse, it offers a great view of the field but compromises the field's integrity. Overall, Antietam has been best preserved, with the possible exception of Shiloh, when compared to other Civil War battlefields and one can study the battle with only minor hindrances.

How did you get first get involved with the Save Historic Antietam Foundation?

After reading Ezra Carman's The Maryland Campaign of September 1862 (as edited by Thomas Clemens and published in two volumes) and poring over the Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam, I became fascinated with the terrain and how it affected the battle. Finally, I had found a battlefield with a (somewhat) contemporary book and map! I live in Washington, D.C. and the battlefield is about seventy miles away so I began spending weekends at the battlefield in Fall 2012 and became a Volunteer in Spring 2013 to increase my understanding of this battle and its military geography. I proposed a project for the 2013 Joseph L. Harsh Memorial Scholarship, awarded by the Save Antietam Historic Foundation for research on the Maryland Campaign of 1862.

Scores of battlefields have been lost to urbanization. Of those that remain, very few are well-preserved. Without a view of the terrain, it is impossible to understand what happened at any battle. A group like SHAF works "to promote the preservation and restoration of the scenic area in and around Antietam Battlefield."

What did you propose?

Although much has been written about the battle of Antietam, the primary focus has been on the leadership, strategy and tactics, and the casualties associated with the 1862 Maryland Campaign. Three crucial topics that have yet remained unexplored are: the geology of the battlefield, the 1862 topographical features of the battlefield and how they affected the battle, and the mapping of the battlefield during the years of 1893 to 1908. My paper examined these three subjects with the intent of providing a fuller understanding of the battle and the battlefield of Antietam.

Drawing of a portion of the Antietam BattlefieldMy objective was to provide a topographical companion to the Carman Manuscript. It was my goal to identify all relevant terrain features mentioned in the Manuscript (as edited by Thomas Clemens) and then locate them on the 1908 Atlas with GPS coordinates assigned to each terrain feature. Upon completion of this project, the terrain features would be readily identifiable on both the Atlas and battlefield as well as indexed to Volume II of Carman/Clemens. In the end, I set to make an Index of Coordinates so all terrain features could easily be found by Antietam enthusiasts.

Drawing of a portion of the Antietam BattlefieldMy objective was to provide a topographical companion to the Carman Manuscript. It was my goal to identify all relevant terrain features mentioned in the Manuscript (as edited by Thomas Clemens) and then locate them on the 1908 Atlas with GPS coordinates assigned to each terrain feature. Upon completion of this project, the terrain features would be readily identifiable on both the Atlas and battlefield as well as indexed to Volume II of Carman/Clemens. In the end, I set to make an Index of Coordinates so all terrain features could easily be found by Antietam enthusiasts.

This project would help clarify Carman's eyewitness' mentions of various topographical and man-made features. For example, Carman wrote about action in the West Woods, that "the two right companies of the regiment crossed the wood road and took cover of a rock ledge in open ground." I found the rock ledge the troops hid behind and assigned its GPS coordinate. Another example, on the advance of the 14th CT near Mumma's Farm, Carman wrote "on the right of the 14th CT, on high ground, well protected by the fences of Mumma's lane and the outcropping rocks, was the detachment of the 1st DE..." Again, I located the high ground, fences and outcropping rocks and assigned all three unique GPS coordinates. These and many other topographical and man-made references were identified in this research. The outcome of my project gave a better understanding of exact locations of units and events—something useful to historians, park rangers, guides, volunteers, and visitors.

What resources were particularly useful in your planning?

Aside from the Clemens edition, I consulted the Ezra A. Carman papers in the Manuscripts and Archives Division of The New York Public Library, which contains correspondence related to Carman's work as a Civil War historian. From the National Archives in Washington, the records of the Antietam Board (part of the Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General) and the Records of the Adjutant General's Office. Finally the Atlas editions and the Library of Congress' Antietam Battlefield Board Maps of 1893 &1894.

After all this preparation, how did it go, marking the GPS coordinates in the field?

As time passed, I found my project was growing into something much larger than I had originally proposed. As it turned out, accurately locating a GPS coordinate involved quite a bit of work.

While Carman's Manuscript and the Atlas are fantastic resources, looking at a rock ledge on a map made in 1908 versus finding it on the battlefield in 2013 leaves a sizable margin for error if one is unfamiliar with terrain. The vast landscape of the battlefield has changed over the years and, at times, it is very confusing and difficult, if not impossible, to locate a particular terrain feature of which Carman had written about that had affected troop movements during the battle. Is it this hill Boyce's battery retreated behind for cover? Is it the west fence of Hagerstown Pike that the 21st NY got tangled up in? Or is it the east fence? And what about those rock ledges? Did Lawton hide his brigade behind all four ledges or just one?

In order to complete this project, I read and re-read Carman's chapters numerous times and color-coded all things terrain; yellow for corn, blue for water, dark green for ravine, medium green for woods, light green for grass, brown for fence, black for road, red for farms, etc. I narrowed my search and created an Index of Terrain Features that significantly affected troop movements. The criteria for what got listed was simple, for example, if the troops used a hill for cover then the hill went on the Index list. If the troops solely advanced over the hill then the hill did not get listed. I returned to my book and underlined all terrain features that made the cut in purple.

The next step was to locate all the terrain features listed in my Index and get their GPS coordinates. Using the book and a manageable size of Carman's Atlas I proceeded onto the battlefield to locate and identify these terrain features. It was at this time I realized the scope of the project was growing in size. Before the terrain features could be located, the terrain itself needed to be examined. The battlefield is split almost evenly between two geological units, Conococheague (North) and Elbrook (South), with the break at Sunken Lane. This is why specific features occur in certain areas only. For example, the amount of rock ledges found on the northern portion of the field would not be found on the southern portion due to the different sedimentary rocks.

With both a grasp on the battlefield's geology and Carman's 1908 Atlas in hand, the majority of features were located quite easily. GPS coordinates of rock ledges, hills, former fence lines, and ravines filled my notebook. However, some features were difficult to find. Like Carman did, I used some of the veterans letters that included hand-drawings of their positions to find their positions on today's battlefield. These individual maps were precise and the sought after terrain feature was found each time I used the veterans personal maps. By summer's end, I had a completed Index of GPS Coordinates of terrain features that affected troop movements during the battle. I estimate I have a few hundred unique coordinates. This Index can be used in conjunction with the Clemens edition of the Carman Manuscript as a field guide to finding the terrain features on the battlefield. Just like Carman, and the soldiers, now, visitors can also stand on the hill that Boyce hid behind. They can climb over the fence the 21st NY got caught in, or hide behind the rock ledge like Lawton's brigade did, too.

How is this project going to play into your next steps?

I took the licensed battlefield guide written test on April 26 and I passed! Hopefully, with my background in terrain, the tours I provide will be exciting and interesting as I bring both the battle and the landscape alive. In September 2013 I gave a presentation at the Visitor Center of Antietam National Battlefield. Offering speciality tours about specific Brigades on the battlefield is something I'd like to pursue as well. Most visitors only have time for the general tour, but for those who have time to delve deeper, I think microcosm tours bring the reality of the battle that much closer so a visitor can gain a better understanding of what an individual regiment endured versus what two armed mobs on a field did.

More immediately, I next plan to return to NYPL and work solely with the hand-drawn maps made by the vets and sent to Carman, and tell the story of those maps. I find them absolutely fascinating and some are beautiful works of art. These are the maps behind the creation of the Atlas.

Do you have any recommendations for recent scholarship about the Maryland Campaign?

Scholarship about Antietam is predominantly good and offers various points of view. On the "Must Read" list is: Ezra Carman's The Maryland Campaign of 1862 Volumes I & II (ed. Thomas Clemens), Joseph Harsh's Taken at the Flood, D. Scott Hartwig's To Antietam Creek, and Ethan Rafuse's McClellan's War. There are more books covering topics ranging from Antietam's farmsteads, hospitals, and civilians to individual regimental stories. The Harsh Scholarship is the beginning of a series of original research funded by SHAF. The first scholarship recipient was Daniel Vermilya and his paper, "Perceptions not Realities: The Army of the Potomac in the Maryland Campaign" was just published and available at the Antietam Bookstore. My paper, "The Best War Map Ever Made: Ezra Carman and the Atlas of the Battlefield of Antietam will hopefully be published by the end of the year.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.