Biblio File

The Time Machine: Reading List 2013

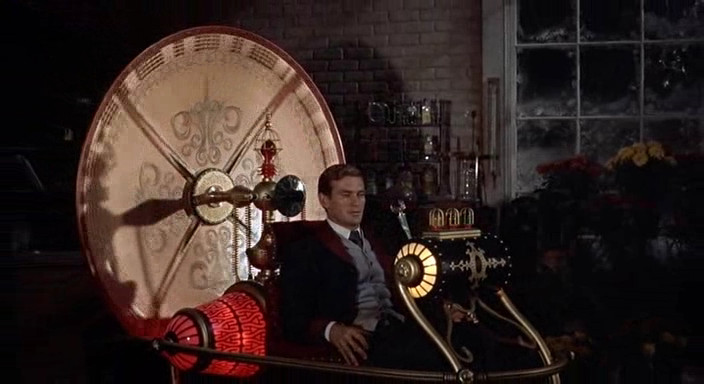

A favorite movie of my adolescent years was The Time Machine. I saw it again and again, and the special effects—state-of-the-art at the time, cheesy now—are still etched in my memory. How exciting to watch the time traveler step into his machine, a kind of overstuffed Victorian armchair set inside an ornate sleigh, and push the lever forward. A candle burned out in an instant, a garden snail shot across the windowsill, suns and moons sped across the sky, leaves budded, snow fell, faster and faster and faster, year after year into the future. I was enthralled. I was enchanted.

Little did I dream this would be such a perfect analogy of adult life.

Some years ago, while considering ideas for my next blog post, I thought I might compile a list of the books I had read during the previous year—not only to keep a record for myself (tending, as I do, to forget things), but to share my bookish enthusiasms and perhaps offer a few recommendations to anyone who might be interested. Then, before I knew it, another list came along, and then another, and now, in what seems the blink of an eye, it is four years later, and I am putting together yet another list of books read during the improbable year just passed. I don't think it is coincidental that the best new novels I read this year have all dealt, more or less, with questions of the past and the future, how the two interconnect, and what impact one has on the other.

* * *

I started The Black House, by Peter May, on my wife's recommendation, expecting nothing more than a good mystery novel with an exotic setting. It turned out to be much deeper and more involving than that. The mystery element is a strong one. Two grisly but very similar murders, one in Edinburgh the other on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, bring Scottish detective Fin Macleod, originally from Lewis, back to the home and the people he left years ago. Here, in this bleak landscape, his own past becomes a palpable presence, haunted by ghosts and tinged with regrets. He learns how one mistake can alter a lifetime. The twin strands of the plot, involving Macleod's tainted past and the mysteries of the present, come together in a thrilling climax.

The impact of the past on the present plays an especially important role in The Right-Hand Shore, by Christopher Tilghman. This novel, one of my favorites not only of this year but of any year, begins in the aftermath of the Civil War and traces three generations of a family inhabiting Mason's Retreat, a vast property on the Eastern shore of Maryland. While the family tries to come to terms with the horrors of its slave-owning past, their former slaves, now farm workers and servants in the mansion, try to adjust to the ambiguities of their new freedom. Each episode is as sharply honed as lived experience. Boyhood friends get caught up in the turbulent racial waters. An interracial love story is both gripping and exhilirating, joyous and terrifying. The obsessive attempt to turn the plantation into a huge peach orchard is as riveting as any thriller; whether the peaches blossom or rot becomes the pivot on which the characters' lives and perhaps society itself will rise or fall. This majestic book carried me along on its strong current of poetry, wit, and drama for days, and just writing about it now I can immediately recapture its spell.

* * *

No matter what the historical period, men in their fifth decade are sometimes seized by wayward impulses. For Charles Dickens, that impulse took the form of an eighteen year-old actress. His motivations were a mixture of the pure and the carnal, saturated by guilt, complicated by a compulsion for secrecy, and all wrapped up in hypocritical Victorian notions of women and respectability. I still haven't seen the film, but I found the book surprisingly, engrossingly readable. The reconstruction of Ellen Ternan's life, an existence carefully and systematically hidden from view in the hopes of keeping Dickens's public reputation unblemished, is as engrossing as a detective story.

* * *

* * *

* * *

Now, although these books can be read out of sequence, I recommend approaching them as I did, in the order they first appeared, starting with The Various Haunts of Men. More than the characters in most crime series, these people keep evolving. The events in one book will change lives in the next. The more you read, the more deeply invested you become.

Her latest novel, The Soul of Discretion, is due out this year. I don't know how I can stand to wait.

* * *

* * *

Time may go speeding ahead like a runaway locomotive, but nothing remains more timeless than Shakespeare's plays.

January: Summer, Edith Wharton; The Various Haunts of Men, Susan Hill; The Bradbury Chronicles, Sam Weller; The Pure in Heart, Susan Hill; Old New York, Edith Wharton; The Risk of Darkness, Susan Hill; The Mother's Recompense, Edith Wharton

February: The Vows of Silence, Susan Hill; A Backward Glance, Edith Wharton; Watching the Dark, Peter Robinson

March: The Stories of Ray Bradbury; A Feast of Words: The Triumph of Edith Wharton, Cynthia Griffin Wolf; The Shadows in the Street, Susan Hill; Dear Life, Alice Munro; Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

April: The New York Stories of Edith Wharton; The Right-Hand Shore, Christopher Tilghman; Renoir, My Father, Jean Renoir; The Betrayal of Trust, Susan Hill

May: The Reef, Edith Wharton; A Question of Identity, Susan Hill; Walks With Men, Ann Beattie; Married Love, Tessa Hadley; I Can't Complain, Elinor Lipman; Roman Fever, Edith Wharton; Swimming Home, Deborah Levy

June: Sanctuary, Edith Wharton; Living With Shakespeare; Gallows View, Peter Robinson; A Dedicated Man, Peter Robinson

July: The Interestings, Meg Wolitzer; The View From Penthouse B, Elinor Lipman

August: Collected Stories 1891-1910, Edith Wharton; My Dear Governess: The Letters of Edith Wharton to Anna Bahlmann; The Children, Edith Wharton; No Gifts From Chance: A Biography of Edith Wharton, Shari Benstock; Russ & Daughters: Reflections and Recipes From the House that Herring Built, Mark Russ Federman

September: The Woman Upstairs, Claire Messud; Twilight Sleep, Edith Wharton; Creole Belle, James Lee Burke; Last Friends, Jane Gardam

October: The End of the Point, Elizabeth Garver; Light of the World, James Lee Burke; Glimpses of the Moon, Edith Wharton; A Treacherous Paradise, Henning Mankell

Novermber: The Black House, Peter May; The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens; The Minor Adjustment Beauty Salon, Alexander McCall Smith

December: Collected Stories 1911-1937, Edith Wharton; The Virgin in the Ice, Ellis Peters; A Morbid Taste For Bones, Ellis Peters; One Corpse Too Many, Ellis Peters; Twelfth Night, William Shakespeare; As You Like It, William Shakespeare; Much Ado About Nothing, William Shakespeare

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

The Time Machine: Reading List 2013 by Robert Armitage

Submitted by Keith Glutting (not verified) on February 13, 2014 - 12:57pm

I've been waiting and waiting

Submitted by JF (not verified) on February 19, 2014 - 3:00pm

RA's Books for 2013

Submitted by Bob K (not verified) on February 19, 2014 - 7:01pm

Robert Armitage's book recommendations and comments

Submitted by Susan O'Connor ... (not verified) on February 20, 2014 - 2:28pm