Food for Thought

From Sanitary Fairs to "The Settlement": Early Charity Cookbooks

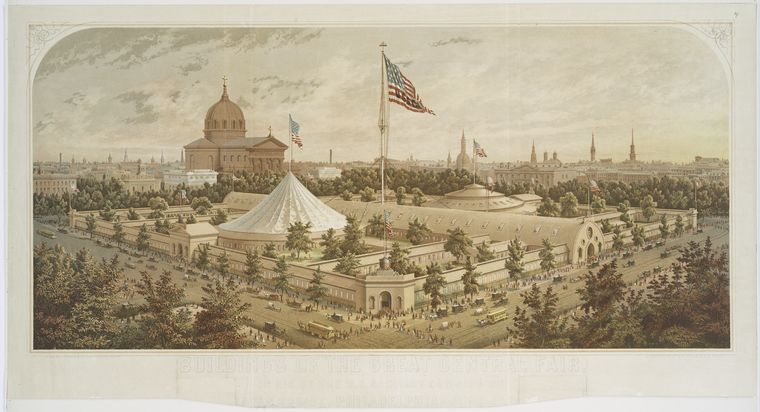

One hundred and fifty years ago, as the Civil War raged, the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was busy raising money to improve conditions for Union soldiers. Early on in the war, people realized that, in addition to the terrible loss of life during the battles, an appalling number of casualties occurred because of poor sanitation and inadequate medical care. One very successful method of fundraising by the USSC was "Sanitary Fairs"—exhibitions and festivals held throughout the Northern states. Merchandise for sale at the fairs might include clothing, toys, tobacco, furniture, and, of course, food. At some point, someone had the brilliant idea of selling cookbooks during and after the fair, featuring recipes for food and beverages sold at the fair. Thus was born the community cookbook, also known as the charity or fundraising cookbook.

(Incidentally, the papers of the USSC Army of the Potomac are held in NYPL's Manuscripts and Archives Division. The archive has been cataloged and is now open to researchers; see Susan Waide's posts on this important project).

The idea of publishing cookbooks to raise money for charity soon caught on with women's groups in churches, hospitals, and other organizations. In the next few decades, hundreds of charity cookbooks were published, although very few have survived. Jewish women's groups, too, took part in this endeavour. The earliest known Jewish community cookbook is the Fair Cook Book, published by Temple Emanuel of Denver in 1888. (See Professor Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett's article on this cookbook). From the 19th century to the present, tens of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of charity cookbooks have been published. Of all these cookbooks, the most successful and long-lived by far has been The Settlement cook book.

Founded around the turn of the twentieth century in Milwaukee, "The Settlement" was a community center for immigrant girls that aimed to help them adjust to their new land. The girls—mostly Jewish and Italian, but other nationalities as well—were taught English and gained useful skills like sewing, darning, and cooking. The Settlement's Jewish founder and cooking teacher, Lizzie (Mrs. Simon) Kander, published a cookbook in 1901 to support the Settlement. With clear recipes suitable for the beginning and experienced cook alike, it was an immediate hit—and a surprising hit to the Settlement's Board of Directors, who took so little interest in Mrs. Kander's cookbook that they forced her to raise the $18 it would cost to publish the book. Since 1901, the cookbook has gone through over 30 editions and has sold some two million copies. It's not a Jewish cookbook per se, but there are some recipes for Jewish classics like "Purim cookies" (now usually called Hamentashen) and gefilte fish.

The only surviving original example (that is, not a reprint) of the 1901 edition is found in the Milwaukee Public Library. The Dorot Jewish Division owns an original example of the exceedingly rare 2nd edition from 1903 (available online from Google Books; also online is the 10th edition [1920] from Hathi Trust).

The Settlement cook book, 1903

The Settlement cook book, 1903

The Settlement cook book, 1915

The Settlement cook book, 1915

The 1915 edition is notable for its "Liberty supplement"—a selection of recipes intended to help cooks deal with expected shortages when the United States entered the First World War. There are recipes for "meat extenders" like "baked vegetable hash" and "mutton with eggplant," and desserts like "wheatless pastry" and "sugarless baked apples." There's also a recipe for "war mayonnaise" which, puzzlingly, doesn't seem to be much different from regular mayonnaise: it contains vinegar, lemon juice, boiling water, egg yolks, mustard, salt, pepper, and 1 cup of oil.

The Settlement cook book, 1950s

The Settlement cook book, 1950s  The Settlement cook book, 1940s

The Settlement cook book, 1940s

Why has The Settlement cook book been so successful? The main reason, I think, is simply that it's a very good, reliable, all-purpose cookbook. Millions of cookbooks have been published over the past century, and many of them are specialized. There are, for example, cookbooks for appliances (microwave, slow cooker, pressure cooker, bread machine), special diets (low carb, high carb, low fat, low sugar, gluten-free), and cookbooks for just about every ethnic group or nationality. Good all-purpose cookbooks are less common. From recent decades, I especially like Nikki & David Goldbeck's American Wholefoods Cuisine and Mark Bittman's How to Cook Everything, as well as Spice and Spirit: The Complete Kosher-Jewish Cookbook, which has lots of good basic recipes. The Settlement cook book is a classic all-purpose cookbook: not fancy, not gourmet, just lots of tested recipes that any cook can rely on.

And just think: Lizzie Kander might not have raised all that money for The Settlement had it not been for the Sanitary Fairs all those years ago.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Earlier "charitable" cook book than Sanitary Fairs

Submitted by Lynn Nelson (not verified) on June 16, 2014 - 5:06pm