NYC Neighborhoods

The Woolworth Building: The Cathedral of Commerce

April 24th sees the one hundredth anniversary of the opening of the Woolworth Building, at 233 Broadway. In 1913 the Woolworth Building was the tallest inhabited building in the world, and would remain so until the opening of the Chrysler Building, in 1929. The Milstein Division's collections include a series of photographs, taken by the photographer Irving Underhill, that chart the building's construction. This post looks at those photographs, and at the man who commissioned the building's construction, Frank W. Woolworth, and its architect, Cass Gilbert.

Iron and then steel frames, made the construction of very tall buildings possible, negating the necessity of the thick masonry walls of earlier buildings. With a sturdy, yet light steel frame buildings could be strong, tall, and elegant. It also meant that with relatively thin walls, and increased height a property developer might generate maximum profit from a small area of very expensive real estate. Technology at the end of the 19th century meant that skyscrapers could now be built as high as proportion would allow.

The first skyscraper in New York City was the Tower Building (Bradford Gilbert), built in 1889. More followed, including famously, the Flat Iron Building (1903), the Singer Tower (1908), and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower (1909). The Woolworth Building (1913) was the last of the great early skyscrapers built before the First World War. Construction of these tall buildings would not fully resume until the 1920s, with the golden age of skyscrapers, culminating in the construction of the Chrysler Building, and the 102-story Empire State Building (1931).

Frank Winfield Woolworth (1854-1919)

It seems appropriate that a man like F.W. Woolworth should be behind the construction of the Woolworth Building. He was keenly aware of the importance of image and brand, and he already knew where to locate a building for full effect. He had supreme business acumen, and appreciated architecture.

Woolworth was born in 1854, in the small town of Rodman, New York. He made his name with the Woolworth's chain of stores, originally selling items at 5 and 10 cents each. Woolworth started out working for other men, most significantly, William Harvey Moore, at his store Augsbury & Moore. In the fall of 1878, Moore's store in Watertown, New York had a 5-cent counter, laden with goods pre-priced at 5 cents. This was not a new idea, but was still something of an innovation. Instead of asking the store clerk to weigh out items, and then price accordingly, as was usual, the customer helped themselves. It was quick, convenient, had a high turnover, and required fewer store clerks to operate. Woolworth realized that what worked for one counter, could work for a whole store. In 1878 he borrowed $300 and opened "The Great Five Cent Store," in Utica, New York.

The store in Utica failed. Undeterred Woolworth opened a 5 and 10-cents store, on June 6, 1879, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The shelves were stocked with attractive, but inexpensive everyday objects—pencils, red napkins, coal shovels, cake tins, boot blacking, police whistles—products designed to catch the eye, but not dent the pocket book, all priced at either 5 or 10 cents. The store was a success. Woolworth attributed this in part to "the thriftiness of the Pennsylvania Dutch." He opened other stores. Some failed, others, like one in Scranton opened in 1880, did not. As more stores opened, Woolworth developed a formula for identifying the best place to locate his businesses: a small town with a prosperous economy, on a busy high street, and in the commercial part of that town. Woolworth's stores caught on, and by 1910 F.W. Woolworth and Company had nearly three hundred Five and Ten Cent Stores, including branches on the up market Ladies Mile, around 5th and 6th Avenue, in Manhattan, and seven branches in the United Kingdom.

Woolworth's colleagues when he worked for William Harvey Moore described him as a poor salesman. He was, however, particularly good at buying, and made a number of trips to Europe, looking for goods to sell in his shops, beginning in the 1890s. While in Europe, Woolworth became enamored of the architecture he saw there. Gail Fenske has noted that "the monumentality and grandeur of Paris's boulevards [...] made a forceful; impression on Woolworth," especially Aristide Boucicaut's luxury superstore, Le Bon Marché (1867) designed by Louis Auguste Boileau, and the Palais Garnier (1861-1875), home of the Paris Opéra, designed by Charles Garnier—Woolworth was a keen opera buff. He was also tremendously impressed by the Houses of Parliament in London. He wondered at the cost of the building, whose Gothic exterior would influence the design of his own Woolworth Building.

Woolworth moved his operations to New York in 1888, and by the early 1900s was a very successful businessman. Originally with offices in the Sun Building, 280 Broadway, Woolworth decided to build his own headquarters. He may have got the idea to build a skyscraper watching the construction of the Singer Building, built in 1908 at 149 Broadway, through the window of his office in the Sun building. Woolworth himself said that he was given the idea to build a skyscraper when visiting Europe, where he was frequently asked about the Singer Building. He realized that the Singer Company had built not just a headquarters, but an international talking point. In 1908 Woolworth began talks with the Irving National Bank regarding the construction of a modest office building to house both companies' headquarters, which would eventually evolve into the world's tallest skyscraper, the Woolworth Building. Beginning in 1910 Woolworth began to take measures to get the building constructed, and within a few months had selected and bought a site, arranged the financing of the project, and chosen an architect.

Woolworth decided to construct his building on a block fronting 229 through 235 Broadway, one of New York's premier shopping thoroughfares, near to City Hall Park, opposite the Post Office. 229 previously had been the site of the American Hotel (1825-1866), managed in the 1830s by William B. Cozzens, a former Tammany Hall politico. The hotel was noted for its succulent dinners, with champagne as cheap and plentiful "as the Croton," and for the "fast young men" who stayed their, and lit their cigars with "dollar bank bills" (New York Times, April 6, 1866). 235 Broadway, was between 1821 and 1836 the home of Philip Hone, Mayor of New York (1826), and in 1851, included the office of The Dagguerran Journal, an early periodical dedicated to the art of photography. The block on which Woolworth built his skyscraper reportedly cost him half of the $13.5 million he paid for the entire project, which he famously paid in cash.

With City government growing, and 500,000 people a day streaming across the Brooklyn Bridge on their way to Manhattan, Woolworth saw the commercial potential of the skyscraper's location, with the building acting as a "giant signboard," advertising the greatness of his company, and as a way to make money, leasing floors to other companies, which would in turn raise the value of his real estate. On August 10, 1912, speaking to the Dry Goods Reporter, Woolworth said

My idea was purely commercial. I saw possibilities of making this the greatest income producing property in which I could invest my money.

Cass Gilbert (1859-1934)

Cass Gilbert was born in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1859. His father was a surveyor for the United States Coast Survey. In 1864 the Gilbert family moved to St. Paul, Minnesota, where, in 1876, Cass began work at the office of local architect Abraham M. Radcliffe. He left Radcliffe's firm in 1878, to enroll in the architecture program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. On graduation, in 1880 he visited Europe, to study and travel. On his return, Gilbert went work for the firm McKim, Mead & White, who had or were to design many New York landmarks, including Penn Station (1910, razed 1963), the Morgan Library & Museum (1900-06), Washington Arch (1892), and Brooklyn Museum (1895). McKim, Mead & White were exponents of an architectural style known as Beaux-Arts, which filtered classical Greek and Roman styles through the Parisian school École des Beaux-Arts, and of the City Beautiful Movement, a North American style of architecture and city planning that focused on beauty and monumental grandeur.

Gilbert, who had been Stanford White's assistant, returned to St. Paul in 1882, to set up an office with fellow architect James Knox Taylor. Gilbert and Knox completed a number of commissions together in Minnesota, including the Endicott building, which gained the architects a national reputation. In 1898 Gilbert moved his office to New York. In 1902 he received his first big commission, from the Office of the Supervising Architect, one James Knox Taylor, to build the U.S. Custom House, at 1 Bowling Green. Completed in 1907, the building combined Beaux-Arts and the City Beautiful Movement to great effect, and cemented Gilbert's reputation in New York.

When the two men met, in 1910 to discuss the contract to design a skyscraper, Woolworth was impressed by Gilbert's up front manner. At their meeting, the architect drew a sketch for the Woolworth Building, and jotted down some costs next to it. Typically architects at the time would agree to contracts before drawings were made. Gilbert realized that potential clients would be impressed by drawings, and would be more likely to award contracts to an architect who invested time and effort in that process before money was discussed.

Woolworth had already commissioned the construction of a number of buildings, including his mansion at 990 Fifth Avenue (1901-1927), and the impressive North Queen Street Woolworth store, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (1901), that included 5 floors of office space and a theater above the store itself. Woolworth awarded the contract to Cass Gilbert. The photograph on the left, taken in 1931, is from the Library of Congress digital collections.

Construction

Originally Woolworth had intended to build a modest bank and office building for his company and his co-sponsors the Irving National Bank, but as the project went on, and the building was finished, it had grown in scope, and become the tallest occupied building in the world. Soon after it was completed Woolworth was to buy the Irving National Banks share of the skyscraper, reducing the bank's status to that of tenant.

The contract for constructing the Woolworth Building was awarded to the Thompson-Starrett Company, headed by Louis J. Horowitz. The company was in operation from 1899 until 1968, and was, along with the George A. Fuller Company, a pioneer in the construction of early skyscrapers in New York City. Thompson-Starrett's list of construction projects includes numerous historic buildings; the Equitable Building in Manhattan (1915), the former General Motors Building in Detroit (1923), the American Stock Exchange (1930), the City of New York Municipal Building (1914), Union Station, Washington, D.C. (1907), and the New York World's Fair New York State Pavilion (1964).

Construction began April, 1910, with the demolition of existing buildings on the site, and by August 26, 1911, the building's foundations were complete. Construction of the skyscraper's steel frame began August 15, 1911, and rose at the rate of 1½ stories a week, closely followed by the "brick layers attaching terra cotta cladding." By April 6, 1912, the steel frame had reached the thirtieth floor, the top of the main block, and the forty-seventh storey of the main tower by May 30. The topping out ceremony took place, as the last rivet was driven into the summit of the building on July 1, 1912. The building was completed, in record time, by April 1913. Gilbert's Custom House had taken 6 years to build. (Fenske, 186)

As the skyscraper went up New York newspapers (and hundreds nationwide) provided running commentaries on the building's ascent up and beyond the city's skyline. Not yet built, Woolworth's building had captured the public's attention, and was already generating enormous publicity. Woolworth decided to record the building's construction for posterity. He employed a commercial photographer, Irving Underhill, who had his studio on the corner of Broadway and Park Place, opposite the site, to document at regular intervals, the construction of the building. Underhill's photographs were sent out to Woolworth's stores all over the country, and can be seen in the gallery below.

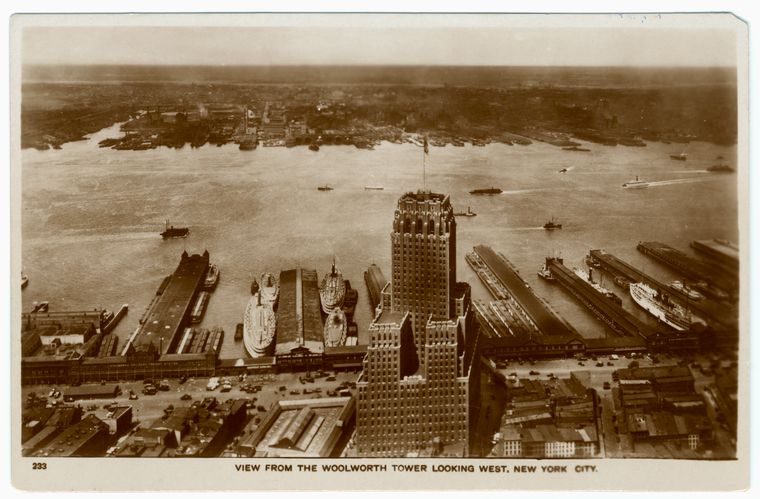

Underhill's photographs below, views of City Hall Park and Broadway South, were taken in 1908 (top) and 1913 (bottom), and show the area before and after the construction of the Woolworth Building. The skyscraper dominates the landscape, and is so tall that the second photograph's horizon appears considerably lower than in Underhill's 1908 picture, an effort required to squeeze the building into the photograph's frame.

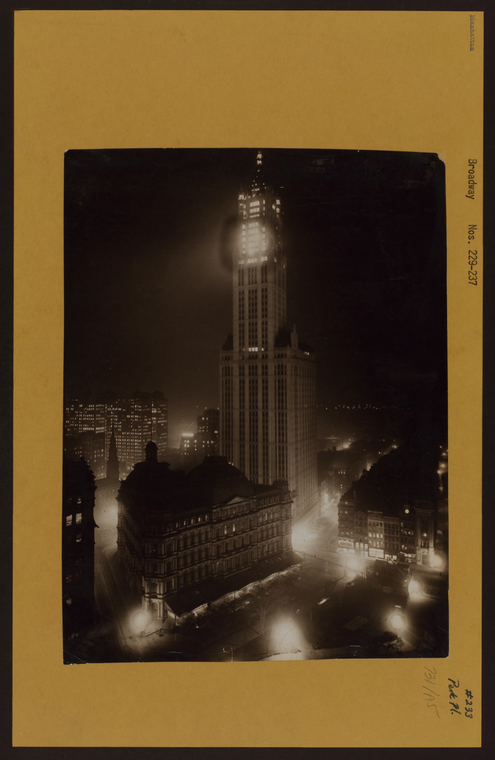

The opening ceremony, held by Woolworth, in Cass Gilbert's honor, took place on April 24, 1913. President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in the Whitehouse and 80,000 light bulbs came to life, illuminating the skyscraper, and there was a banquet on the 27th floor, attended by 900 guests.

The opening ceremony, held by Woolworth, in Cass Gilbert's honor, took place on April 24, 1913. President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button in the Whitehouse and 80,000 light bulbs came to life, illuminating the skyscraper, and there was a banquet on the 27th floor, attended by 900 guests.

The building

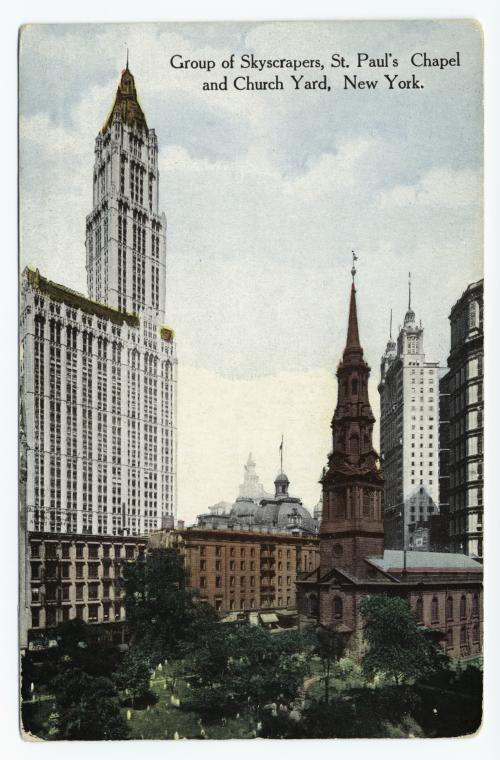

A Landmark Preservation Commission report of 1983 describes the Woolworth Building as a 60-story skyscraper that rises 792 feet above street-level. It occupies the entire block front along Broadway, between Barclay Street and Park Place, and features a 30-story tower built on a 30-story base. Its construction consists of a steel frame, designed by engineer Gunvald Aus, and covered with masonry and Atlantic terra cotta, and features carving and decorative motifs that are Gothic in inspiration.

In 1913, superlatives and numbers abounded. The Wall Street Journal, from April 26, 1913, captures the mood, describing the building's vital statistics in detail:

By its combination of Italian, French and Renaissance architecture with Gothic steeple, in creamy white stone and terra cotta, the result is a building unique and one of the most beautiful in the world. […] The structure contains over 17,000,000 bricks, 24,000 tons of steel girders, 29 elevators, 13,200,000 cubic feet of space […], 200 feet higher than the Great Pyramid, […] fireproof and smoke-proof stairs […] enough to climb a mountain 4,000 feet high […] 87 miles of electrical wiring […] lamps [that] would light forty miles of waterfront around Manhattan, […] six 2,500 horsepower boilers [that] could lift 100 Statues of Liberty. It weighs 206,000,000 pounds at the caissons […] [and] can withstand wind speeds of 25 miles an hour. […] elevator shafts total two miles, […] there are 48 miles of plumbing, 53,000 pounds of bronze and iron hardware, 3,000 hollow steel doors, 12 miles of marble trim, 12 miles of slate base, 383,325 pounds of red lead, 50,000 cubic yards of sand, 15,000 yards of broken stone, 7,500 tons of terra cotta, 28,000 tons of hollow tile, […] [and [no] wood." And enough glass to cover Union Square.

It was built with bracing to protect against high winds, of a type that had previously been used in the construction of bridges. It has its own power plant (a first), barber shop, restaurant, doctor's office, and swimming pool. Gilbert designed the building in a U-shape, so that every office had access to daylight through one of 2,843 windows, with corridors running through the middle of each floor. The F. W. Woolworth Company, including Woolworth's own marble lined office, located on the 24th floor, occupied 1 ½ floors of the skyscraper until the company sold the building in 1998.

Gilbert included a three-storey high grand arcade entrance, with vaulted ceilings, and glass mosaic windows, and walls and floors made of marble imported from Greece and Italy. Frescos titled 'Commerce' and 'Labor', and a dozen marble busts, including one each of Gilbert and Woolworth adorned the lobby. The grand scale of the building, combined with its Gothic style, led clergyman Dr. S. Parkes Cadman, who attended the opening ceremony, to famously describe the building as "the cathedral of commerce."

The Woolworth Building met with universal acclaim. Architecture critic Montgomery Schuyler wrote the text for a brochure privately printed by Woolworth, titled The Woolworth Building that praised the its 'gracious shape,' and labeled it "an ornament of the city." Julian Huxley, the English scientist, described the Woolworth building as "a fairy story, gigantically and triumphantly come to life." French art historian Andre Michel called it "an epoch making work," and Japanese architect Matusnosuke Moriyama told the New York Times that "worlds opinion of American architecture will be different now." (Landmark Preservation Commission, 1983).

It should be noted that although Dr. Cadman popularized the name, the first recorded instance of the Woolworth Building being dubbed the Cathedral of Commerce appears in the New York Times, April 27, 1913. Alan Francis, an English visitor to New York, interviewed in a peice for the New York Times, described the Woolworth Building as "a source of both astonishment and inspiration," though he was appalled by "the rubbish which is heaped about it." Not withstanding Francis's displeasure at the trash littered streets surrounding the building, he did go on to say "Perhaps the phrase which best expresses it is that it appears to be a cathedral of commerce." (SM12)

Further reading

Gail Fenske's book The Skyscraper and the City, a source of much of the information in this post, is the book about Woolworth Building. Detailed, and full of illustrations.

Landmark Preservation Commission reports on the Woolworth Building, available free online, include detailed descriptions of the building's architectural features, and biographies of Cass Gilbert and Frank Winfield Woolworth.

Similarly the National Historic Landmark nomination form for the Woolworth Building is also available online:

New York Public Library's Art & Architecture Division has a number of materials pertaining to the history of skyscrapers, the Woolworth Building, Cass Gilbert, artists files, and the history of architecture. Included in that collection is The Woolworth Building, by the architecture critic Montgomery Shuyler, privately printed for Woolworth to distribute amongst friends.

See also the Library's Digital Gallery for images of the Woolworth Building, and maps of downtown Manhattan, that chart the days before, during, and after the construction of the Woolworth Building.

The Milstein Division's collections, in addition to Irving Underhill's photographic prints of the construction of the Woolworth Building, comprise books, digitized historic newspapers, pamphlets, clippings files, photographs, and postcards pertaining to the history of the Woolworth Building.

There are several texts from the period, about the Woolworth Building, available free online, including:

- The Cathedral of Commerce / Edwin A. Cochrane, with a forward by S. Parkes Cadman, 1916.

- Above the Clouds and Old New York / H. Addington Bruce, 1913. [a contemporary visitors guide].

- The Master Builders: A Record of the Construction of the World's Highest Commercial Structure / Hugh McAtamney, 1913.

Search the Library's online catalog:

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

softbound book of the Cathedral of Commerce copywrite 1917

Submitted by Rita Sullivan (not verified) on September 3, 2018 - 11:21am