Barrier-Free Library

Art and Low Vision: The Artist’s Eyes

In his very first email to me, Michael Marmor, professor and past chair of ophthalmology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, wrote:

Your point that your view is original and valid on its own is important. I try to teach students that low vision or color “blindness” are not necessarily faulty vision... they are “different” vision. And may in some ways be better, or at least just as valid, depending on what you are trying to do. You have more of an “impressionist” view of a distant landscape than others with perfect vision — it's not better or worse, but alternative.

About a year ago I started reading Marmor and James Ravin’s The Artist’s Eyes: Vision and the History of Art. Most artists are usually reluctant to read books that could be considered technical or scientific, especially if their subject relates to art, but I needed to answer a certain question and hoped that the book would help me somehow. And it did, as it seeks to determine the links between the work of some well-known painters and certain visual disorders.

About a year ago I started reading Marmor and James Ravin’s The Artist’s Eyes: Vision and the History of Art. Most artists are usually reluctant to read books that could be considered technical or scientific, especially if their subject relates to art, but I needed to answer a certain question and hoped that the book would help me somehow. And it did, as it seeks to determine the links between the work of some well-known painters and certain visual disorders.

Degas (1834-1917) probably had a retinal disease that caused central, or macular, damage, and the primary effect of such disease would be visual blur, or poor acuity. […] By the 1890s, Degas was making frequent references in his letters to poor eyesight as well as to difficulty with reading and writing… […] By the turn of the twentieth century, he was quite disabled, with visual acuity of 20/200 to 20/400. Remarkably, he continued to work in pastels until 1912...Degas himself spoke about his eye problems — and I would think he was answering the above question when he said, “I am convinced that these differences in vision are of no importance. One sees as one wishes to see. It’s false; and it is that falsity that constitutes art.”

This is the artist’s natural tendency — to believe that his art is the result of choice in that “one sees as one wishes to see.” It has been shown by scientists, however, that dyslexics, for example, or people with visual disorders like strabismus, are disproportionately overrepresented in the artistic population. This might lead one to think that differences in vision and the brain are possibly of some importance.

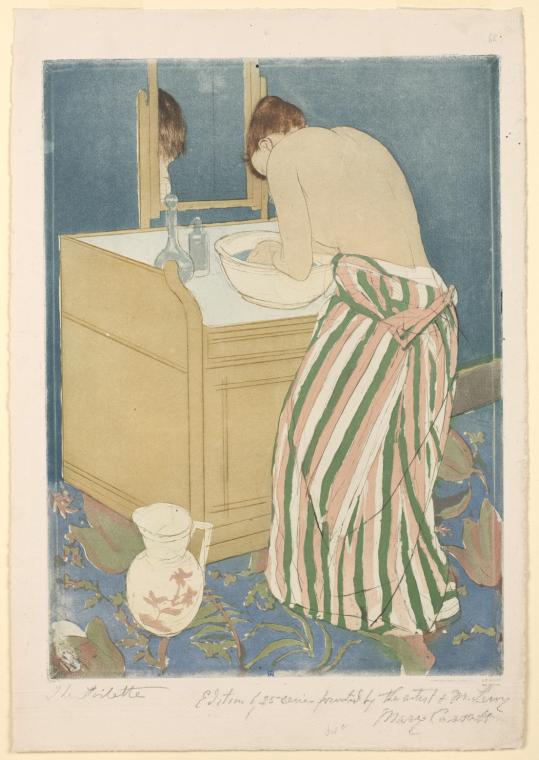

In The Artist’s Eyes, Marmor and Ravin discuss not only Degas but also Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), who suffered from chronic infection of the tear sac; the Irish painter Paul Henry (1876-1958), who was color deficient; Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), who had cataracts; and many more artists with or without vision loss — even the presbyopic potter Euphronios in ancient Athens. They also explain in a coherent way how the eye works and why glasses are needed, or how we interpret images of low contrast and images that combine multiple perspectives.

Fotis Flevotomos, Sunflowers and Lamp, iPad drawing © 2012. In this picture there is substantial luminance difference among the various colors, so objects and depth are easily recognizable.The question of artistic freedom and the dipole of choice-necessity occurred to me quite recently after rereading a section in The Artist’s Eyes titled “Equiluminance and Art,” which refers to colors of equal brightness. Just about the same time I was lucky enough to attend a talk in New York City on the same subject by Margaret Livingstone, a professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. The point made was that our ability to see depth, spatial organization and motion is carried by a color-blind part of our visual system, which means that when two or more objects or colors are equiluminant (of equal brightness), they look flat and shimmery — we don’t have a clear sense as to whether they are moving or not. This made me think a great deal about my own work and the fact that my paintings often lack tone contrast. I have ocular albinism and always have had trouble perceiving depth or understanding where things are coming from and how fast they move — my constant feeling is that they just arrive in my face. So it might be the reproduction of this kind of effect, I realized, that I am subconsciously aiming at, since most of the colors in my pictures are usually of equal luminance (see, for example, the iPad drawing below titled Washington Square). To me, this is a tangible argument as to why low vision is not faulty vision but, as Marmor says, alternative vision.

Fotis Flevotomos, Sunflowers and Lamp, iPad drawing © 2012. In this picture there is substantial luminance difference among the various colors, so objects and depth are easily recognizable.The question of artistic freedom and the dipole of choice-necessity occurred to me quite recently after rereading a section in The Artist’s Eyes titled “Equiluminance and Art,” which refers to colors of equal brightness. Just about the same time I was lucky enough to attend a talk in New York City on the same subject by Margaret Livingstone, a professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. The point made was that our ability to see depth, spatial organization and motion is carried by a color-blind part of our visual system, which means that when two or more objects or colors are equiluminant (of equal brightness), they look flat and shimmery — we don’t have a clear sense as to whether they are moving or not. This made me think a great deal about my own work and the fact that my paintings often lack tone contrast. I have ocular albinism and always have had trouble perceiving depth or understanding where things are coming from and how fast they move — my constant feeling is that they just arrive in my face. So it might be the reproduction of this kind of effect, I realized, that I am subconsciously aiming at, since most of the colors in my pictures are usually of equal luminance (see, for example, the iPad drawing below titled Washington Square). To me, this is a tangible argument as to why low vision is not faulty vision but, as Marmor says, alternative vision.

Fotis Flevotomos, Washington Square, iPad drawing © 2012. The landscape looks shimmery and relatively flat because, as the black-and-white image shows, there is little luminance difference among the green and red areas.See these links for more about art and low vision:

Fotis Flevotomos, Washington Square, iPad drawing © 2012. The landscape looks shimmery and relatively flat because, as the black-and-white image shows, there is little luminance difference among the green and red areas.See these links for more about art and low vision:

- Art and Low Vision: A List of Accessible Museums in New York City

- Art and Low Vision: A Multi-Sensory Museum Experience

- Drawing on the iPad by artist Fotis Flevotomos

- Celebrating Art Beyond Sight: The Value of Creating and Appreciating Art for Those with Low Vision

- Barrier-Free Library Channel

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Remarkable Story

Submitted by Janielle (not verified) on January 9, 2013 - 11:25am