Musical of the Month

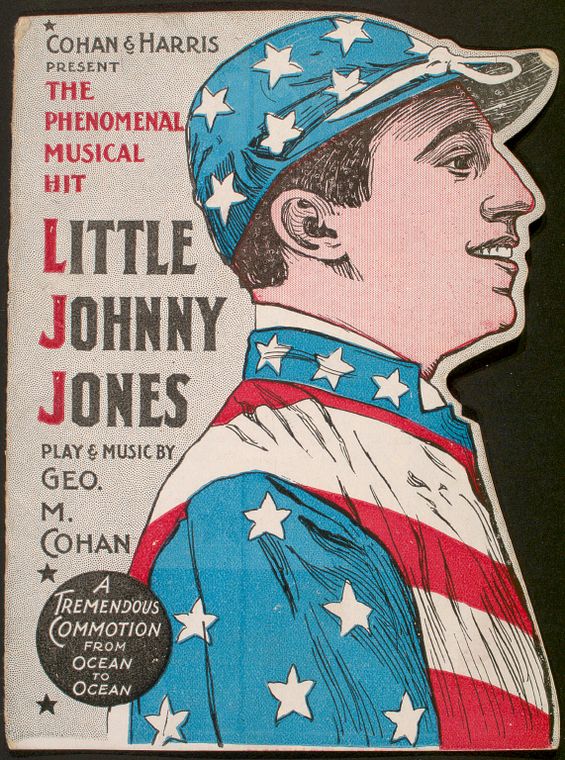

Musical of the Month: Little Johnny Jones

A guest post by Elizabeth Titrington Craft.

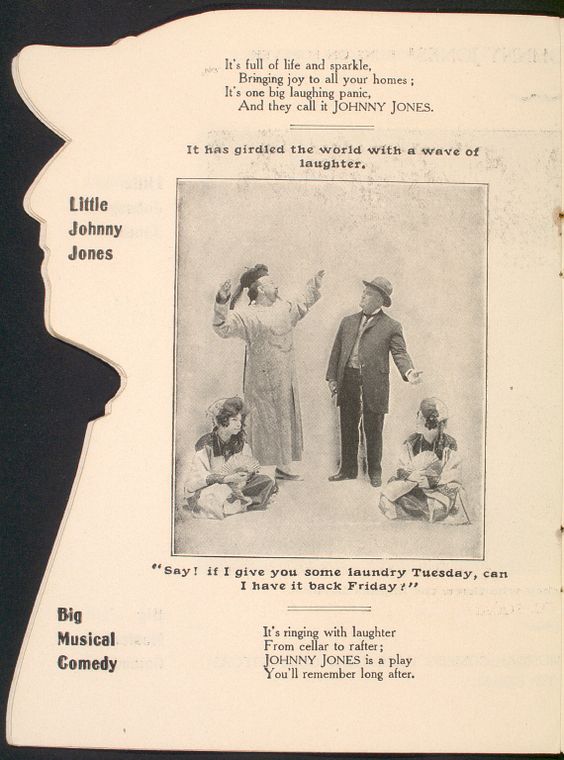

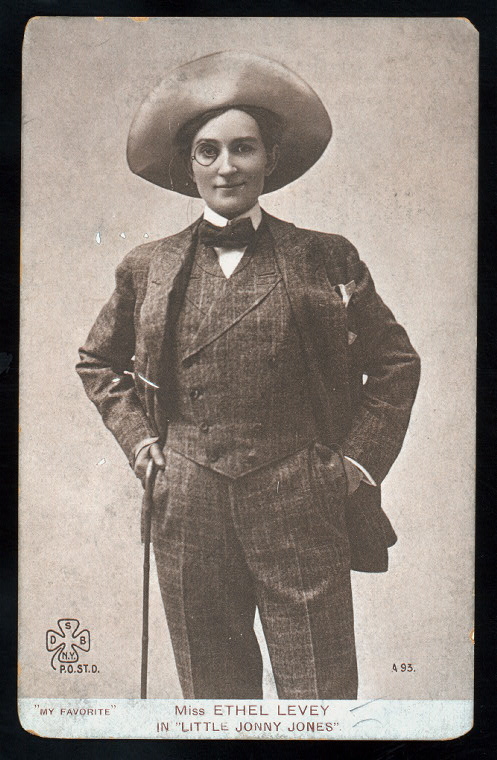

With its fast pace, colloquial language, and patriotic themes and tunes, Little Johnny Jones proved a prototypical Cohan musical. A certain plot template emerges from Cohan's so-called "flag plays," many of which were set abroad: Americans run amok in London or Paris, where fortune-hunting British noblemen, in cahoots with title-hunting American parents, create hurdles for brash young Yankee heroes and their charming sweethearts. In Little Johnny Jones, the musical's title character, loosely based on the real-life jockey Tod Sloan, has traveled to England to ride in the English Derby. Jones is in love with the heiress Goldie Gates, but Goldie's aunt Mrs. Kenworth, a wealthy widow and the leader of the San Francisco Female Reformers, has traveled to England to arrange Goldie's marriage to a British earl. Goldie intervenes, however. Unbeknownst to her aunt or Jones, she, too, has made the trip abroad, disguising herself first as a French mademoiselle and then posing as the earl himself. Meanwhile, the dastardly villain Anthony Anstey, "king" of San Francisco's Chinese lottery, has become betrothed to Mrs. Kenworth in order to reap her riches and quash her reform efforts. When Jones is accused of throwing the Derby, it looks like not only his honor but also his chance with Goldie is lost. But Whitney Wilson, the mysterious eccentric who turns out to be an undercover investigator, exposes Anstey as the crooked agent behind Jones's set-up. In the end, Wilson takes down the Chinese lottery, Mrs. Kenworth learns her lesson that an upright American beats an English earl any day, and Jones and Gates are happily reunited.

Amidst the upheaval wrought by industrialization, imperialism, and immigration, Little Johnny Jones informed audiences in overt and more insidious ways about what and who qualified as true-blue American. The cast list found in the libretto at the Museum of the City of New York and on playbills used the national label liberally, describing Johnny Jones as "the American Jockey" and Anstey as "an American Gambler." Cohan was billed in playbills and advertisements as "the Yankee Doodle Comedian." Starring as Jones, Cohan epitomized his own vision of the model American – young and energetic, honest and forthright, and a bit cocksure. In the entrance number "Yankee Doodle Boy," Jones introduces himself as patriotism personified:

I'm the kid that's all the candy,

I'm a Yankee Doodle Dandy,

I'm glad I am,

[Chorus]: So's Uncle Sam

The refrain, which begins with the opening lines of this post, hammers home this personification of patriotism. The song is laden with musical and lyrical references from other well-known tunes, and some critics decried Cohan's lack of originality. But listeners loved the "brassy and bass-drummy" sound (in the words of one writer).

It may seem ironic that a musical so fixated on patriotism and American identity is set abroad. In part, setting the show in England allowed for suitably "exotic" colorful scenery and fun novelty numbers like "'Op in Me 'Ansom," in which a chorus of hansom cab drivers and female reformers sing about touring London. The European-American encounter of these shows also served up ample opportunities for a somewhat chauvinistic brand of humor, as when the heroine Goldie (in disguise as Mlle. Fanchonette) asks Anstey, "What makes the Americans so proud of their country?" "Other countries," he quips in response. In another scene, the humorously undiplomatic and apparently oblivious Wilson delivers London a backhanded compliment:

Wilson. I certainly had a good time here in Pittsburgh.

Starter. Pittsburgh?

Wilson. I mean, London. Ain't it funny I always get these two towns mixed? London and Pittsburgh. But say, no joking, London is a great town for fun.

Starter. Right you are, sir.

. . .

Wilson. And you take it from me, for a good time London makes Worcester and Springfield look like thirty cents.

The meeting of Europeans and Americans provided plentiful fodder for jokes while sending the clear message that traveling abroad may be fun, but life at home in the United States is best.

Nor do the outsiders within the United States' borders escape commentary, though Cohan's messages about immigrant Americans are decidedly ambivalent. The Chinese Americans and, in absentia, southern European immigrant characters remain outsiders. And in the second verse of "Yankee Doodle Boy," Jones employs nativist rhetoric, citing his parents' old-stock lineage to justify his Americanness:

Father's name was Hezekiah,

Mother's name was Ann Mariah,

Yanks through and through,

[Chorus:] Red, white and blue.

. . .

My mother's mother was a Yankee true,

My father's father was a Yankee too;

. . .

[Chorus:] Oh, say can you see anything about my pedigree that's phony?

This is a surprising statement from Cohan given that he, as a third-generation Irish American, could hardly claim such a lineage. And indeed, Cohan also shows his Irish American character, Timothy D. McGee, to be a "good man" and a good American, ultimately pairing him with the wealthy Mrs. Kenworth.

The music of Little Johnny Jones, though not particularly innovative, was pleasant and catchy, with Tin Pan Alley forms and generous doses of ragtime syncopation. "As a composer, I could never find use for over four or five notes in my musical numbers," Cohan wrote in a letter to a friend, and he claimed he "never got any further than…four F-sharp chords." But while his music does have a straightforward simplicity to it, Cohan undersells his musical know-how. Musically and lyrically as well as dramatically, he was a craftsman. And his delivery of his songs as singer-dancer-actor, in his distinctive manner of speak-singing, helped put them over. The patriotic style he used in "Yankee Doodle Boy" was the most striking, but the philosophical "Life's a Funny Proposition After All" and "Give My Regards to Broadway," which could be either warmly wistful or jauntily energetic depending on the performance, also became favorites.

Although the first Broadway run of Little Johnny Jones was relatively brief (52 performances), Cohan responded by taking the show on the road and then returning to New York in 1905 and 1907, for a combined total of over 200 New York performances. Cohan wrote in his autobiography, "It was the one and only Broadway 'comeback' I have ever known or heard of." Reviews were mixed. A few raved, and a few ranted. (Life described the 1907 production as "the apotheosis of stage vulgarity.") Most, though, conceded finding it enjoyable as entertainment if not up to the standards of serious drama. Most important to Cohan, it received the endorsement of the box office and made him a Broadway figure of note.

![The Yankee Doodle boy / [words and music by] Geo. M. Cohan.,Little Johnny Jones. Yankee Doodle boy. Vocal score., Digital ID g98c154_001, New York Public Library The Yankee Doodle boy / [words and music by] Geo. M. Cohan.,Little Johnny Jones. Yankee Doodle boy. Vocal score., Digital ID g98c154_001, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=g98c154_001&t=w)

Now, as for the early twentieth-century audiences and critics, Cohan's proud and exuberant "flag waving" provokes strong reactions. Some may find it endearing, others embarrassing. His conception of American identity may seem wholesome, outmoded, or even objectionable. As we pack up the flags and sparklers from the Fourth of July, the debates over what – and whom – we celebrate rage on.

A note on the text from Doug:

The text below was transcribed by Ann Fraistat and encoded for eReading by me. It is based on a copy at the Museum of the City of New York which did not include any of the lyrics. However, many of the songs can be found in NYPL's Digital Gallery.

| File type | What it's for |

|---|---|

| ePub | eBook readers (except Kindle) |

| Mobi | Kindle |

| Adobe Acrobat | |

| HTML | Web browsers |

| Plain Text | Just about anything |

| TEI | Digital Humanities Geeks |

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

1905 recordings

Submitted by LauraFrankos (not verified) on July 22, 2012 - 2:14pm

Recordings

Submitted by Doug Reside on July 23, 2012 - 8:44am

Jokes about little Johnny

Submitted by JesseyJones (not verified) on September 14, 2019 - 9:53am