Archives

United States Sanitary Commission Processing Project: A Day at the (Civil War) Office

Anna Peterson, a graduate student at the University of Michigan's School of Information, recently helped us organize some correspondence of the USSC's Hospital Directory office in Philadelphia. Here are Anna's impressions of a letter she found in the collection during her internship with the Manuscripts and Archives Division:

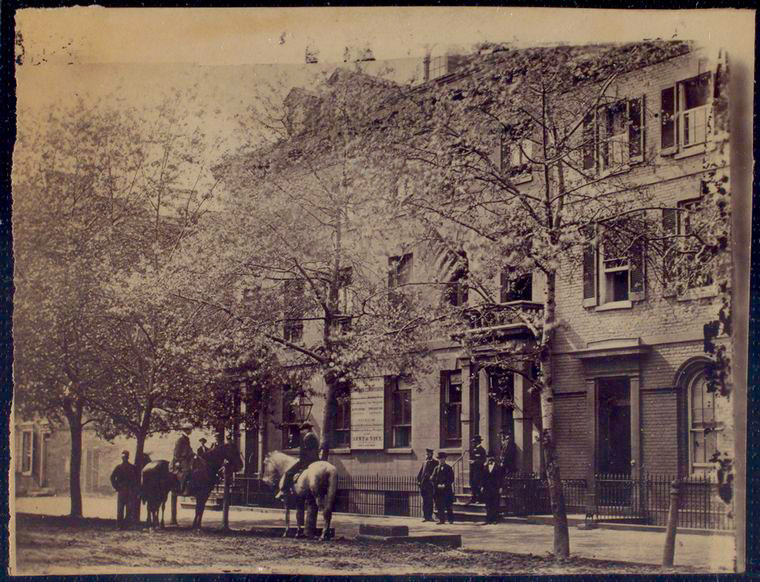

The Hospital Directory, with offices in Washington, New York, Philadelphia and Louisville, was established in 1862 to collect and record information concerning the location of sick and wounded soldiers in U.S. Army hospitals. Members of the public who had lost contact with their relatives or friends contacted the Directory by letter or visit, in the hopes of learning their condition or whereabouts.

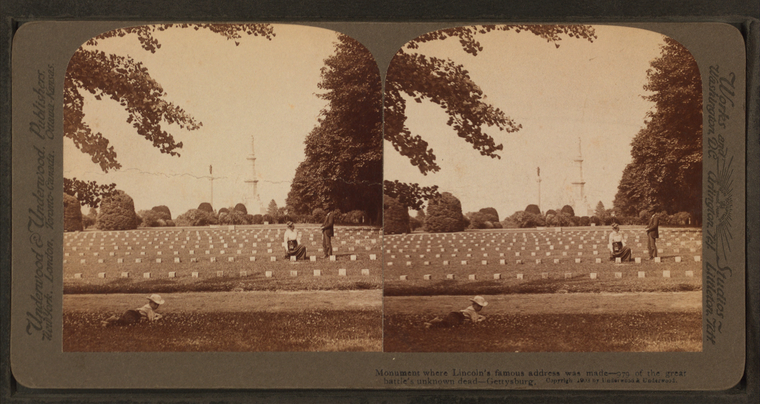

Many letters in this record group reveal the anguish felt by the families and friends of missing soldiers during the Civil War. An inter-agency letter, written not long after the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3), offers another perspective into the search for those soldiers, particularly the administrative feats required to gain information about their fates after a major battle with heavy casualties.

On July 30th, 1863, Hospital Directory superintendent John Bowne, at USSC headquarters in Washington, wrote to H.A. de France, head of the Directory's Philadelphia office. In the letter, Bowne admonishes de France for his tardy reply to Bowne's inquiry regarding a soldier by the name of McGiff. His letter also offers a glimpse into the logistics of the USSC's presence in Gettysburg after the battle.

John Bowne to H.A. de France, July 30, 1863

John Bowne to H.A. de France, July 30, 1863

The brief administrative delay in the information regarding soldier McGiff caused the soldier's mother much pain, according to Bowne, as she was "sobbing and distressed at the probable fate of her boy, and left the office mourning not only for her loss of him but also for her fruitless and unwise expenditure of time and money" in traveling to the office. In this case, we see clearly the urgency of the agency's activities.

Perhaps most fascinating is de France's unofficial response, written in pencil on the letter's bottom and reverse side. Here, de France explains the cause of the information's tardy arrival in Washington, offering an unexpected view into the office's daily activities.

H. A. de France's pencilled "response"

H. A. de France's pencilled "response"

![U.S. Sanitary Commission, 1307 Chestnut St., Phila[delphia], July 4, 1865. Decorations & illumination for the return of peace to our beloved country. , Digital ID 1150295, New York Public Library U.S. Sanitary Commission, 1307 Chestnut St., Phila[delphia], July 4, 1865. Decorations & illumination for the return of peace to our beloved country. , Digital ID 1150295, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=1150295&t=w)

Mr. Webb had left the office his work then having been ended

Mr. Morton had gone to see about the wagons

Mr. Anderson had gone home sick

Mr. Belcher was busy downstairs and I was

alone in the office the whole afternoon.

One afternoon at 1307 Chestnut Street, continued

One afternoon at 1307 Chestnut Street, continued

We do not know if de France also offered this explanation to Bowne or if he simply kept it on record in the Philadelphia office. Instead, we do see an impassioned defense of his work and can perceive the human challenges that the USSC faced in its mission to provide information about missing soldiers.

—Anna Peterson

![Headquarters U.S. Sanitary Commission Gettysburgh [sic]. ,[Wagon from Headquarters U.S. Sanitary Commission Gettysburgh [sic]. ,[Wagon from](https://images.nypl.org/?id=1150192&t=w)

And what of soldier McGiff? Further insight into de France's and Bowne's untiring efforts to find this one man out of thousands of wounded soldiers will be gained by reading letters written by both men in the USSC's Hospital Directory office correspondence, as well as materials in the Hospital Directory "letter of inquiry" files.

There we find a Washington Hospital Directory file for Christopher McGiff, a private in the 119th New York Infantry, Company A, who turns out to be the soldier in question. It contains a letter of introduction for his mother, Mary McGiff, a "poor woman" traveling from New York City to Washington in search of her son. Although the Hospital Directory offices could not locate him in any hospital at that time, they continued to search for him, writing to his regimental surgeon on August 17, 1863. The reply: "The last we heard of him is that, the 1st Lieut. of his Comp. saw him falling wounded; he supposes in the chest during the action of the 1st July at Gettysburg & since that time he has been reported missing. The impression of the first Lieut. is that he was then killed."

Anna's encounter with H.A. de France's letter represents the beginning of similar individual stories that researchers can pursue, using archival guides to find related materials in the United States Sanitary Commission records, when the collection is made available to the public in 2013. (Other resources within the NYPL and beyond await the curious detective.)

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

A day in the Office.

Submitted by Debra DiFranco ... (not verified) on July 28, 2012 - 4:48pm