To prepare for the presentation “

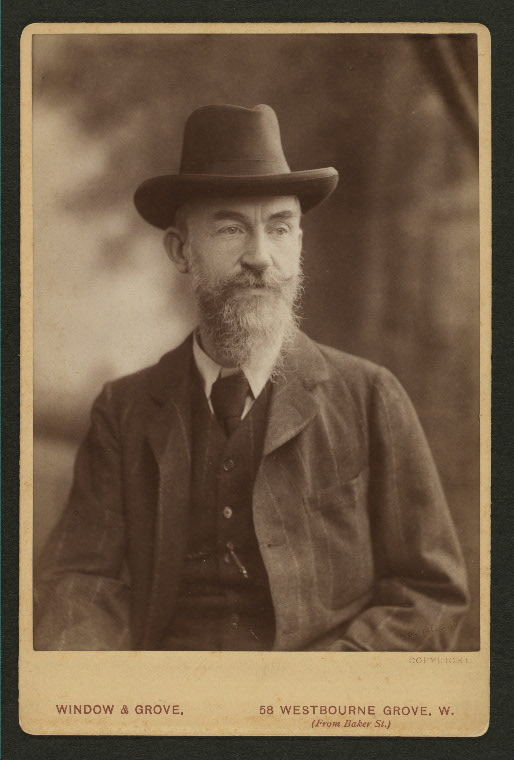

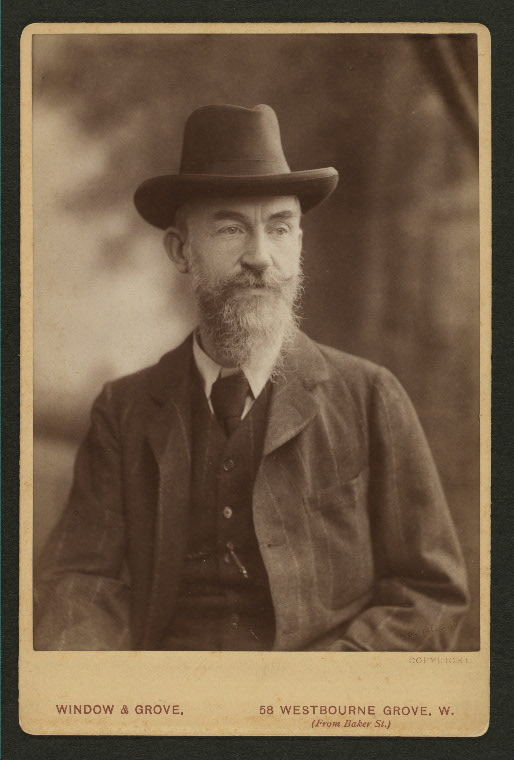

Subversive Shaw: An Introduction to the Life and Work of Bernard Shaw,” I ended 2010 and started 2011 by obsessively reading Shaw’s complete dramatic works. Since these range from the monumental five-play sequence Back to Methuselah to the 10-page marionette skit Shakes versus Shav, I remained occupied for several gratifying months. Certainly not everything by Shaw is of equal value, but even the slightest plays are witty, vigorous, and worth reading — at least once. My problem is that any time I read any play (and here I was gulping down 60 of them in a relatively short span), it releases some long-suppressed, primal urge to tread the boards myself. Over the past year, on the interior stage where reading takes place, I seem to have acted out all the great Shavian parts, from Henry Higgins to Saint Joan, Major Barbara to the Devil.

From this solid trunk of a reading project sprang several fascinating branches. The Holroyd biography of Shaw led me to the Margot Peters biography, with its focus on Shaw’s relationships and infatuations with the notable actresses of the day. Then I turned to Shaw’s correspondence with two of the greatest of those Victorian actresses, Mrs. Patrick Campbell and Ellen Terry — love letters written in the uniquely Shavian style. My newly sparked interest in theater brought me back to Holroyd again and his joint biography A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving and their Families, whose background ranged from the early Victorian stage, as represented by Terry and Irving, to the modern expressionist theater, which was partly shaped by their children.

Then it was serendipitous to find that the new novel by one of my favorite authors, David Lodge, was a fictionalized biography of H. G. Wells, and that it featured, as a minor character, a thoroughly convincing Bernard Shaw. Wells, one of the younger Fabian Society socialists, alienated the elder members, like Shaw, with his startlingly radical views, especially those espousing the doctrine of “free love.” The novel is largely concerned with “free love” and Wells’s multiple romantic and erotic involvements. Although I have qualms about the current vogue for mashing up fiction and biography, Lodge is such a compelling storyteller it didn’t seem to matter.

Seldom do I get beyond the first sentence or two of the fiction reviews in the New York Times Book Review. If the review is so tedious, what hope is there for the novel? Consequently, I end up missing a lot of first-time authors. This year, bypassing the Times for the new book section of the Library, I was lucky enough to discover an enchanting first novel by Helen Simonson. (Strictly speaking, my wife discovered it and passed it on to me when she was finished.) Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand details the growing friendship between two mature people: Major Pettigrew, a starchy retired British officer; and the proprietor of the village food shop, Mrs. Ali, a woman of Pakistani descent. The novel is old-fashioned in the best possible sense — funny, humane, and compulsively readable — but modulated with just the right edge of contemporary sharpness.

How does a book which you might have dismissed in the past suddenly exert a magnetic pull that draws you right in? This year I discovered two authors of whose long-standing literary reputations I was only vaguely aware. When it was first in bookstores, I might have ignored Carol Shield’s The Stone Diaries because of its fairly pedestrian book jacket. The title of Jane Gardam’s fifteenth novel, Old Filth, which first came out in America in 2006, must have struck me as sort of disagreeable and kept me from looking further. Now, however, through some quirk of time, circumstance, and curiosity, I returned to these novels and found them both rich in character and spellbinding in narrative energy. The Stone Diaries, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1995, is the story of a seemingly conventional middle-class woman’s life from her calamitous birth, through her roles as wife, mother, and widow, and finally to her own death. Old Filth is another bittersweet life, this time of an aging London barrister, Edward Feathers, called “Old Filth”. Why? On the first page, spotting the elderly figure in London’s Inner Temple, the Common Sergeant explains, "Great advocate, judge and — bit of a wit. Said to have invented FILTH — Failed in London. Try Hong Kong. He tried Hong Kong." The best thing about latching on to authors in mid-career is that you can read them backwards and forwards at the same time, catching up on their previous work while waiting for their new books to appear.

As usual, my reading year was peppered with mysteries and suspense novels. One of the best was the oldest, The Woman in White, a book I had read so many years ago there was nothing left but the vague impression of a musty old Victorian contrivance. How different it seemed on rereading! I brought the Penguin edition on vacation this summer, and read it during those blissfully idle intervals between days on the beach and having to make a decision about which restaurant to go to for dinner. Over the past few years I have rediscovered Wilkie Collins, and I’m always surprised by how compelling his fiction can be. The Woman in White has a complex plot which bounces along briskly, and it’s easy to see how it held its audience for months through the first serial publication. There are some genuinely creepy moments (involving being falsely imprisoned in a lunatic asylum); feisty, independent female characters who go very much against the Victorian grain; and an overwhelmingly evil villain in Count Fosco. (

More about Wilkie Collins in NYPL Blogs.)

I regard Oscar Hijuelos, author of The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, as one of the most engaging and memorable of modern novelists. As far removed as his fiction is from my own experience, it evokes a time, a place, and a culture that seem as familiar to me as the ticking of my own pulse. When I came across his recent memoir, Thoughts Without Cigarettes, in the middle of December, its effect was even more intense. The aura this book created hovered about me throughout Christmas and the New Year and will probably continue for a long time to come. Not only were his reminiscences like listening to good stories told by an old friend, they afforded me an added edge of personal identification. Although we do not share a Cuban-American background, Hijuelos and I are roughly the same age and come from a similar working-class background. His childhood in Morningside Heights was similar to my own in Brooklyn. We both had childhood illnesses requiring lengthy hospital stays; his stories about the dingy old Upper West Side brought back my own years of living there; and I especially enjoyed hearing about his creative writing classes at City College, where he was taught by the likes of Donald Barthelme and Susan Sontag, while I at the same time was enrolled in another writing program at a different CUNY college — and taught by a much less stellar faculty. Empathy, understanding, and a sense of universal significance are the vital responses to any reading experience — and Thoughts Without Cigarettes is rich in all of these — but the simple pleasure of being able to identify with an author's life is not insignificant.

I regard Oscar Hijuelos, author of The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love, as one of the most engaging and memorable of modern novelists. As far removed as his fiction is from my own experience, it evokes a time, a place, and a culture that seem as familiar to me as the ticking of my own pulse. When I came across his recent memoir, Thoughts Without Cigarettes, in the middle of December, its effect was even more intense. The aura this book created hovered about me throughout Christmas and the New Year and will probably continue for a long time to come. Not only were his reminiscences like listening to good stories told by an old friend, they afforded me an added edge of personal identification. Although we do not share a Cuban-American background, Hijuelos and I are roughly the same age and come from a similar working-class background. His childhood in Morningside Heights was similar to my own in Brooklyn. We both had childhood illnesses requiring lengthy hospital stays; his stories about the dingy old Upper West Side brought back my own years of living there; and I especially enjoyed hearing about his creative writing classes at City College, where he was taught by the likes of Donald Barthelme and Susan Sontag, while I at the same time was enrolled in another writing program at a different CUNY college — and taught by a much less stellar faculty. Empathy, understanding, and a sense of universal significance are the vital responses to any reading experience — and Thoughts Without Cigarettes is rich in all of these — but the simple pleasure of being able to identify with an author's life is not insignificant.

* * *

Other people’s books always intrigue me. As I ride trains or buses, I’m always peeking surreptitiously to see what everyone is reading. But I've noticed that fewer and fewer people seem to be carrying actual books for me to spy on. Those who know and love the book as a physical object have come to seem a band of fanatics with burning eyes, wandering about clutching their sacred relics. Since the number of people with e-book readers has increased, there is no way of telling what might be on their little screens. I don’t imagine they can all have downloaded The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo...

This, then, for better or worse, is one librarian’s list of real books. What next year’s list will hold, only time will tell.

![Long years ago, two lovers quarrled. [first line],Time will tell alone. [first line of chorus],Time will tell / words by Harry S. Miller ; music by H.W. Petrie., Digital ID 1165746, New York Public Library Long years ago, two lovers quarrled. [first line],Time will tell alone. [first line of chorus],Time will tell / words by Harry S. Miller ; music by H.W. Petrie., Digital ID 1165746, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=1165746&t=w)

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

Comments

Bravo! This was the best of

Submitted by JF (not verified) on January 10, 2012 - 11:51am