Everyone Counts: Using the Census in Genealogy Research

—

The best strategy for searching the census is to start with the most recent available census and then work backward in time. Begin genealogy searches with the census if your ancestors were in the United States before 1930. In April of 2012, the 1940 census will become available, and this will be the new threshold for U.S. federal census information. You will most likely find your ancestors in the census, and these can be the first documents that you will use to add evidence to your family stories. To help interpret what you find, use Finding Answers in U.S. Census Records or Your Guide to the Federal Census for Genealogists, Researchers, and Family Historians.

When you do find your ancestors in the census, you will find other significant facts about them. This will further help you locate and interpret other documents. Censuses record family members as a group, so this will be key in connecting one generation to another. This is where you will find out whether it was Aunt Joan or Uncle Joe who was correct about Grandma’s birthplace. You can search the census by name in databases such as Ancestry Library Edition, HeritageQuest, and Fold3. The census is also available on the web through FamilySearch Record Search (only some years) and The Internet Archive (not indexed by name).

There’s a common story told when someone cannot find their ancestors in the census. Usually it involves some sort of outlaw activity such as bootlegging, bank robbery, or a general distrust of the government. However, these ancestors are usually listed in the census. It might just require some search savvy to track them down. The important thing to remember is to be flexible and try many different searches. Creativity and persistence are good qualities to use in census searching.

Here are some tips for searching for your ancestors:

- Do not fill in every search box — this may exclude legitimate results that include your ancestors. Broadening your search will mean more search results to sort through, but it's more likely that the results will include your ancestor.

- If there is a unique or less common name in your family, start with only that name.

- If the name you are searching is extremely common, e.g. “Michael Davis,” then you should add more information to help focus your search.

- If you do not immediately find your ancestors, do not give up. Use alternative spellings of names and be open to new information.

Further notes on spellings:

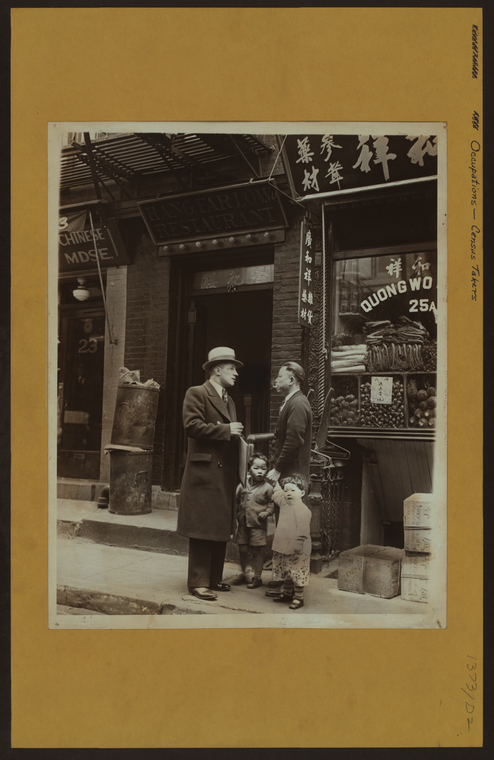

- Census takers did not check identification papers: mistakes, variations, and complete misunderstandings are extraordinarily common.

- Our ancestors may have been semi-literate or illiterate.

- Our ancestors could have used different spellings of their own name, or completely changed their names between two different census years.

- Abbreviations may throw off your search results — “Rbt” for Robert, “Ptk” for Patrick, “Chs” for Charles, etc.

- A person that is known by a nickname in their youth could change to a different version of the name: Molly might become Mary, Bobby might become Bert, etc. This is especially common in homes where a child is named after a parent. For more information on nicknames, consult a name dictionary, which will usually list variations of names.

- There may be more than one person with the same name in the same family: Mary Catherine and Mary Elizabeth might be sisters, but will the census taker record them both as Mary or as Catherine and Elizabeth?

- A person may Anglicize the spelling of a name over time: Roberto in one year of the census may become Bob in the next.

- A person using a different writing system or alphabet, such as Hebrew, Cyrillic, or Chinese, may have no say in how the census taker interpreted and recorded their name using the Roman alphabet.

- Initials may interpreted as a name: “J.M.” may have been recorded as “James,” even if the “J” actually indicated Joseph or Jedediah.

- Reading the handwriting used in the census may be difficult.

![A photographer amid a crowd outdoors.,[Photographer in a crowd.], Digital ID DS_03SCAPB, New York Public Library A photographer amid a crowd outdoors.,[Photographer in a crowd.], Digital ID DS_03SCAPB, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=DS_03SCAPB&t=w)

Every year of the census is slightly different from the next. You can view a complete index of questions for every year of the census, and this will help you determine what type of information you can expect to find.

Some notes on particular census years:

- 1790-1840 censuses include the names of the heads of households only. Everyone else living in a house is listed by approximate ages only.

- 1850 is the first federal census to include the names of all members of a household, including children.

- 1870 is the first census after the Civil War and therefore is the first census to list all African Americans.

- 1880 is the first census to included street addresses.

- 1890 census was mostly destroyed in a fire. Only a fragment of the census remains.

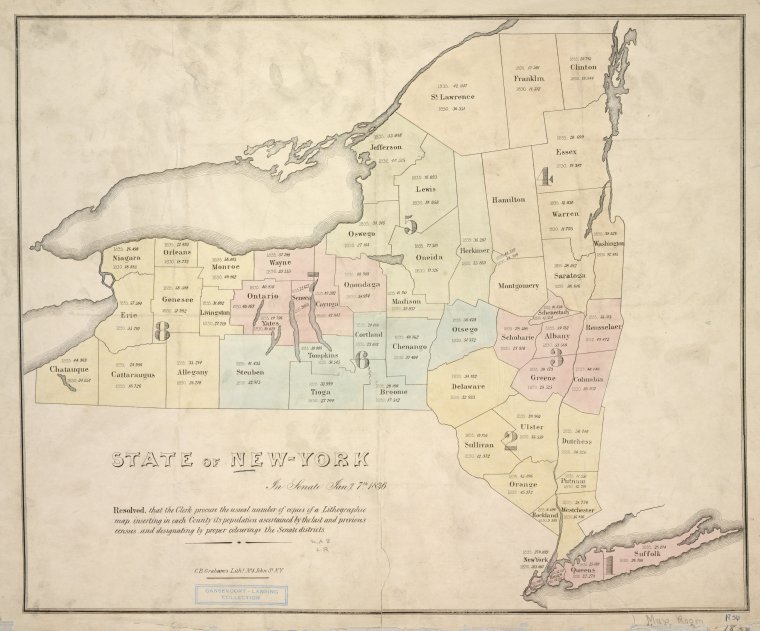

- States and territories joined the United States at various time periods. You should have some idea of the history of the state you are investigating to know what years it was included in the federal census. For example, you will not find Kansas in the census until 1860.

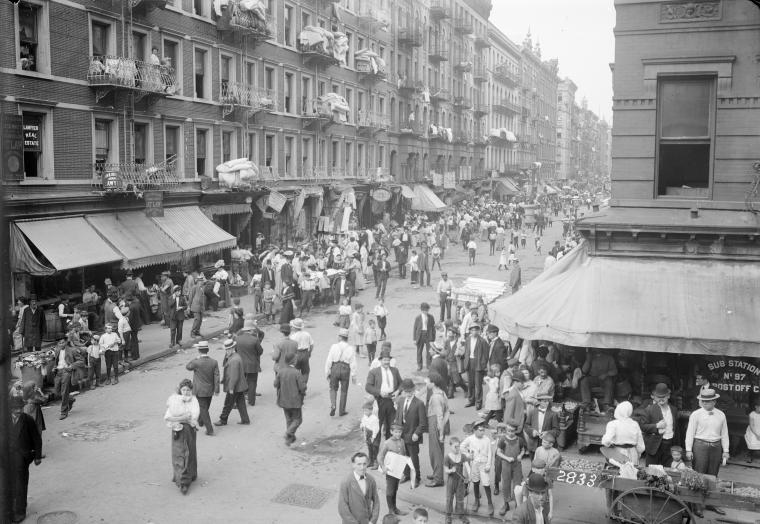

There are other censuses besides the federal census. Many states conducted their own censuses for their own purposes. New York has several years of state censuses, and the Library owns a complete set of the surviving census data. For a complete list of New York state censuses, consult New York State Censuses & Substitutes. New York City even conducted its own census in 1890 using police officers as census takers because it believed that the federal census had undercounted its population. This is a familiar accusation, and luckily this census exists because the federal census for that year was destroyed. Although Ancestry Library Edition has added some of the data from the New York City and New York state censuses, it is currently incomplete and includes only a few books. The Library has a complete set on microfilm.

Other censuses include a separate census of veterans for 1890, separate censuses for American Indians, and Mortality schedules, which are lists of people who died in the year before a census was taken. References such as the Red Book and Census Substitutes and State Census Records include suggestions for census alternatives for each state — which may include ideas for searching tax lists or voter registrations when you can not find an ancestor in the federal census. If you have hit a brick wall in your research, you may want to try alternate strategies.

View this pdf for a list of The New York Public Library’s census holdings, or stop by the Milstein Division in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building for more help with census research.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Oh yes .. the 1940 census

Submitted by Ray (not verified) on December 8, 2011 - 1:48pm