Biblio File

Forsaken Authors: Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway

In the fall the war was always there, but we did not go to it any more.

Hemingway, "In Another Country"

We embrace some authors and remain faithful to them for the rest of our lives; others are good for one mad fling but are then quickly forsaken — we move on and don’t look back.

We embrace some authors and remain faithful to them for the rest of our lives; others are good for one mad fling but are then quickly forsaken — we move on and don’t look back.

If you have not yet seen the appealing new Woody Allen comedy Midnight in Paris, I will tell you that its plot involves a writer who is whisked back in time to what he regards as a golden period — Paris of the 1920s — where he encounters a number of the artistic and literary luminaries who converged there at that time, including F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway. (We will get back to them in a moment.) Nostalgia is the underlying theme of the film. We’ve probably all felt at one time or another that the present moment was a dull, monochromatic place; the future a chaos too frightening to look into; and only the brighter, cleaner, better past was ever worth inhabiting. (Of course this is an illusion, but a benign one.)

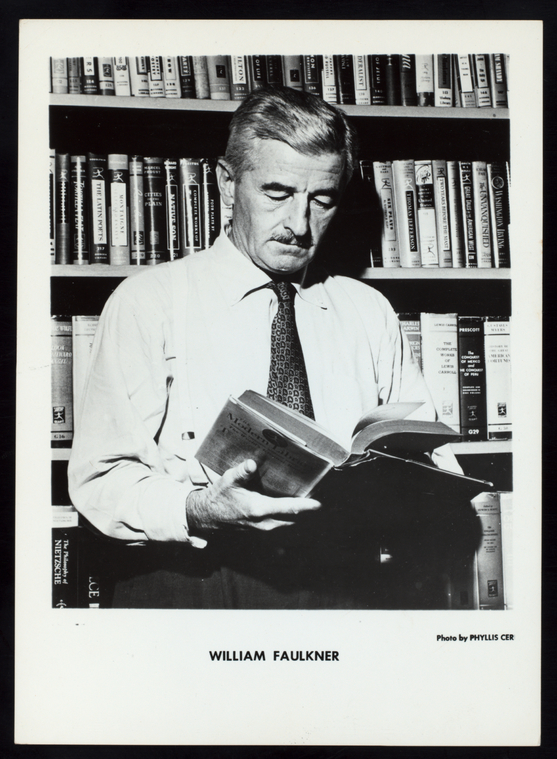

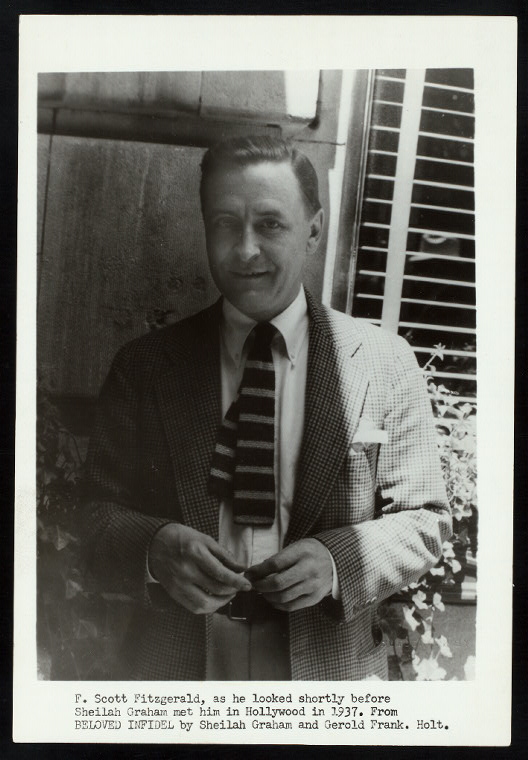

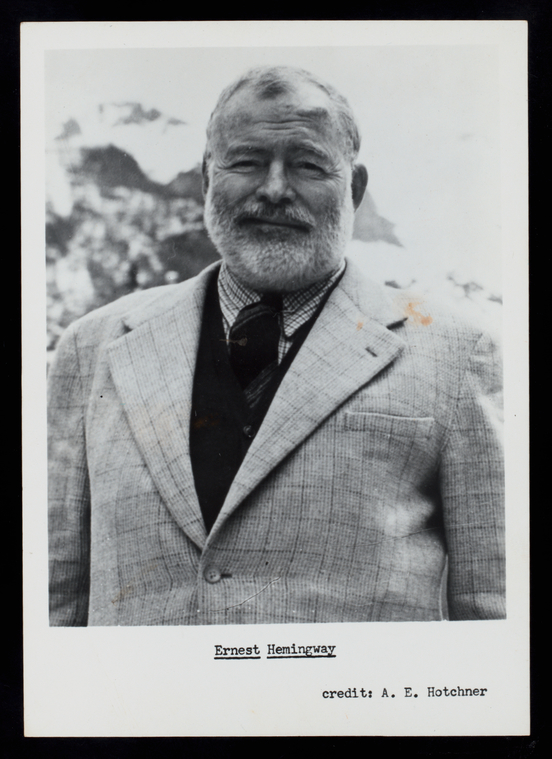

The film made me recall my own fling, many years ago, with Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and — the author I then thought the best of the bunch — William Faulkner. All of these writers are classics, of a sort. Together, they defined American fiction between the 1920s and 1950s. Since I am often struck by vagrant impulses to re-experience certain works of fiction, the appearance of Fitzgerald and Hemingway in Midnight in Paris sparked my desire to go back and see what I might have found so memorable about these authors.

At first, I went to my own bookshelves at home, but soon discovered that Faulkner, Fitzgerald, and Hemingway were all conspicuously absent. No longer did I own those flimsily bound Book of the Month Club editions. Gone were the inexpensive Scribner and Vintage paperbacks of my college days. Alas, the bygone books! Fortunately, I come to work every day at The New York Public Library, where I can get my hands on and re-experience all the meaningful books of my life, whenever I like. (Of course, this is another benign illusion, but one I cling to anyway.) At least I could find enough here to satisfy my brief craving.

What did I remember about these writers? Well, I’m afraid, more of their mythology than their work — Scott and Zelda tossing themselves into fountains; Hemingway on his fishing boat, reeling in the marlin; Scott falling apart in Hollywood while struggling with his unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon; Hemingway in Ketchum, Idaho, with a shotgun. What else? Fitzgerald admired Hemingway. Hemingway didn’t much care for Fitzgerald, and even in his gossipy memoir, A Moveable Feast, accused him of — how to put it politely? — not quite measuring up as a man. Hemingway regarded Faulkner as the only other writer he needed to compete with (or, as Hemingway might have put it, get into the ring with). Faulkner, apparently, minded his own business. Did they have anything in common?

Certainly none of them was any the better for booze.

None of their female characters are especially memorable. I did remember Dilsey, cook and servant to the Compson family in The Sound and the Fury, because Faulkner’s description of her and her family (“they endured”) at one time resonated with me. I also recalled Temple Drake from Sanctuary and the terrible thing that happens to her, but now the terrible thing is more vivid than the character. Fitzgerald sometimes managed a bit of female ventriloquism, but none of his women are otherwise very vivid. In his one indisputably perfect novel, The Great Gatsby, there is a tremendously moving scene in which Gatsby tries to impress his old flame, Daisy Buchanan, with all the shirts his money has been able to buy... but I remembered the scene more than the character of Daisy within it. As for Hemingway, my memory of his female characters doesn’t extend much beyond the image of Ingrid Bergman with short hair in the film version of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943).

They were all ill-served by Hollywood. Fitzgerald and Faulkner squandered a lot of time there to no real purpose. I don’t believe Hemingway fell into the same trap (writing bad scripts for bundles of money), but the movies inspired by his work scarcely did him justice. Except for the presence of Ingrid Bergman with short hair, For Whom the Bell Tolls is three hours poorly spent. In addition, I have vague memories of The Snows of Kilimanjaro, The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, and Hemingway's Adventures of a Young Man — but these are all movies I would not care to revisit.

To reacquaint myself with Faulkner and Hemingway, I turned to that durable old series, the Viking Portable Library, which offers a carefully edited selection of novels, novel excerpts, and stories. No such volume exists for Fitzgerald, but I was able to locate copies of The Great Gatsby and The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. By the time I had called up a handful of books from the stacks, however; the urge to reread any of them was already starting to wither away. Time slogs on, and past loves can’t always be recaptured. The point of this blog post is not how I joyously rediscovered the great American novelists, but how I finally and irrevocably turned my back on them.

To reacquaint myself with Faulkner and Hemingway, I turned to that durable old series, the Viking Portable Library, which offers a carefully edited selection of novels, novel excerpts, and stories. No such volume exists for Fitzgerald, but I was able to locate copies of The Great Gatsby and The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. By the time I had called up a handful of books from the stacks, however; the urge to reread any of them was already starting to wither away. Time slogs on, and past loves can’t always be recaptured. The point of this blog post is not how I joyously rediscovered the great American novelists, but how I finally and irrevocably turned my back on them.

When I thought of Faulkner, his As I Lay Dying, Light in August, and, of course, The Sound and the Fury sprang to mind as cornerstones of my college reading experience. I could still feel the galloping pace of his plots, taste the emotional intensity sparking off the page, and thrill to the excitement of learning how to read each new book that came my way. What I had forgotten was how imponderable his prose could be. I believe it all made sense to me at one time, but now page after page struck me as opaque. A random except from the opening of The Bear will give you some idea what I mean:

It seems I have outlived my enthusiasm for Faulkner.

Returning to Fitzgerald was even more problematic. Even back when I enjoyed reading him, I had to work at enjoying him. His many short stories have faded into a vast wet fog through which only a few glints of light penetrate. These stories were mostly written for the high-paying popular magazines (those of you who are authors and being paid for your efforts in contributor’s copies will not be sympathetic). I seem to remember Fitzgerald once saying that, although his stories had to follow the style and formula of these markets, he tried to inject into each at least one small grain of truth. As far as I was concerned, that grain was too small. Quickly, I set aside the stories and picked up The Great Gatsby, which I have already mentioned and remember as being a small, perfect jewel of a story. I read a few of the opening sentences and could feel them exerting a magnetic pull:

“Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

He didn’t say any more, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. In consequence, I’m inclined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores.

But (here is the moment of truth) I was afraid of going much further. What if the novel did not live up to my early memories? What if I had moved on and Fitzgerald had not? Would my disappointment be greater than my pleasure? I was not prepared to risk it.

When I turned to Hemingway, I was surprised to find him the most interesting of the three authors. This was the reverse of what I used to feel — when I read Hemingway because, well, because one should. My image of Hemingway didn’t extend much beyond that of the smiling big-game hunter with a rifle in one hand and a dead animal in the other. But as I read some of the early stories, I became aware that somewhere at the core of this macho image lurked a rare sensitivity and poetry. The difference between the broken, disillusioned characters of the early stories and the heroes of the bloated late novels who make a show of facing death and loving women truly is probably a critical commonplace, but I was struck sharply by the discrepancy. What might cause such a psychological cleavage? In one of his stories, “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place,” Hemingway wrote:

What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it was all nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. Our nada who art in nada, nada be thy name thy kingdom nada thy will be nada in nada as it is in nada. Give us this nada our daily nada and nada us our nada as we nada our nadas and nada us not into nada but deliver us from nada; pues nada. Hail nothing full of nothing, nothing is with thee.

Impressed as I was with my new vision of the stories, I found after reading a few of them that a few went a long way. I closed the book, neatened my Faulkners, Fitzgeralds, and Hemingways into a pile, and returned them to the Library’s shelves. I do not think I will be returning to them. To paraphrase Hemingway: In the library the books were always there, but I did not go to them any more. I’m not saying these authors shouldn’t be read, read carefully, and re-read as often as one pleases. I’m simply saying how glad I am that I found each of them in the time that was best for me, and now I'm free to move on.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

I'm glad, as always, to read

Submitted by JF (not verified) on December 7, 2011 - 2:53pm

So True

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on December 15, 2011 - 7:26pm

Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Faulkner

Submitted by Geraldine Nathan (not verified) on February 28, 2012 - 6:14pm

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Submitted by Geraldine Nathan (not verified) on March 5, 2012 - 3:30pm

Golden Age of American Literature

Submitted by wml (not verified) on October 11, 2019 - 12:27am