Biblio File

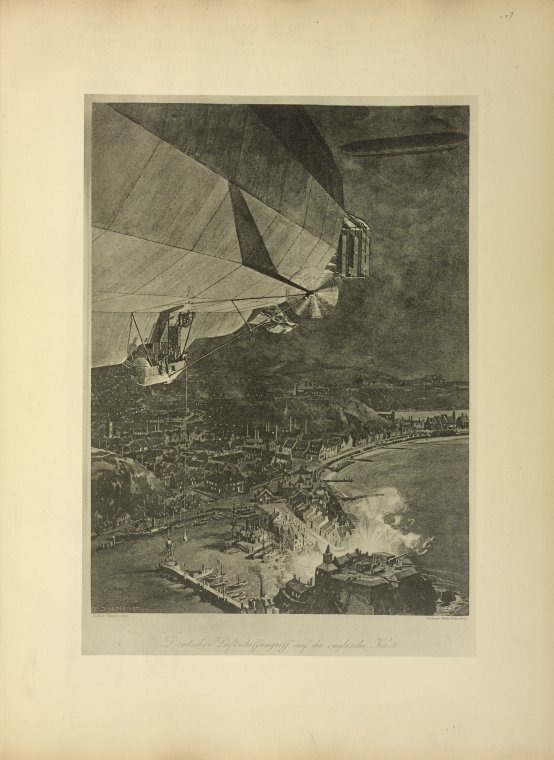

Subversive Shaw, Part 3: Common Sense About the War

"The hag Sedition was your mother, and Perversity begot you. Mischief was your midwife and Misrule your nurse, and Unreason brought you up at her feet — no other ancestry and rearing had you, you freakish homunculus, germinated outside of lawful procreation." — Fellow playwright Henry Arthur Jones, on Bernard Shaw and his anti-war stance

But any look back at the historical picture convinces me that the world was never really much different, except during those periods when it was painted in even grimmer strokes.

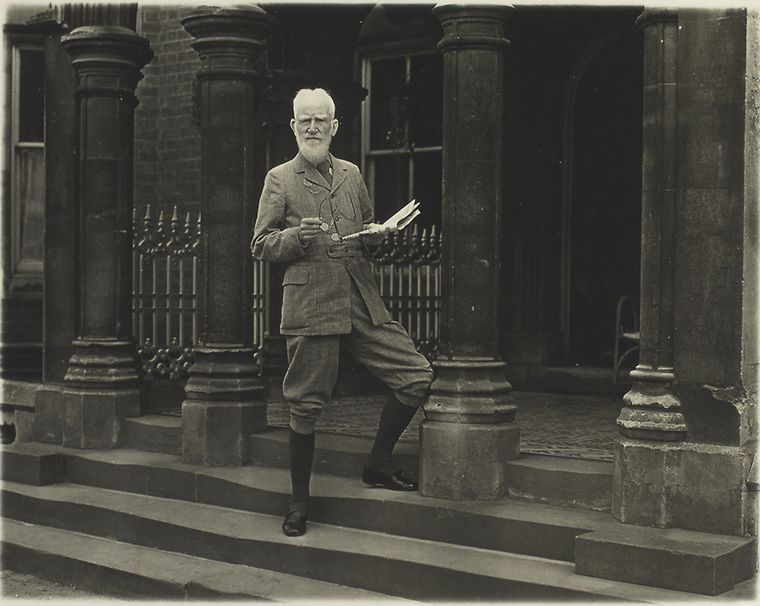

To prepare for the recent Library talk "Subversive Shaw: An Introduction to the Life and Work of George Bernard Shaw," I spent a good chunk of the past year reading work by and about that irascible Irishman. Although I included some of my thoughts on Shaw in Parts One and Two of this blog series, he continues to fascinate me. His life, which lasted as long as anyone's is likely to last (with his wits and energies still remarkably intact), coincided with many of the world's darkest moments. Shaw was born as the Crimean War was coming to end, lived to see the dropping of the Atomic Bomb, and had as constant backdrop to his middle years the Boer War, the Russian Revolution, both World Wars, and at least a dozen other military conflicts involving Great Britain. Not an easy task to keep your faith against those odds, but Shaw managed as well as anybody could.

As well as being one of the great playwrights of the twentieth century, Shaw was a zealous social reformer and, for a good portion of his life, an indefatigable optimist — a man who believed that humankind could and would improve itself, that people needed only to will their own perfection.

I will discuss Shaw's views on war, politics, religion, culture, and sex during the next free presentation of "Subversive Shaw," to be given on Thursday, November 10 at 2:15 p.m. in the South Court classrooms at the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. The program will be repeated at the same time on Friday, December 2.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

I enjoyed this post

Submitted by JF (not verified) on November 2, 2011 - 11:11am