Biblio File, Archives, Lifelong Learning

Celebrating the Centennial: The Tilden Library

Recently, a large-scale drawing came to the attention of Print Collection staff, whose workspace (which I share) is on the third floor of the Schwarzman Building. It was signed "Vernon Howe Bailey, '09," and it appeared to be an early view of the building's Main Reading Room, showing elegantly clad gentlemen and ladies reading or quietly conversing in the gracious surroundings. But two things were puzzling about it. One was the date, 1909, and the other was the inscription on the back: "Tilden Library." No one who works in this building could fail to know that it opened to the public in 1911, and that it never bore an individual's name until 2008, when it was named for Mr. Schwarzman in gratitude for a donation that is expected to help finance a sweeping transformation of its interior over the next several years.

The Bailey drawing as it appeared in Harper's Weekly, 1909 (detail)

The Bailey drawing as it appeared in Harper's Weekly, 1909 (detail)

But the inscription "Tilden Library" on our drawing remained puzzling.

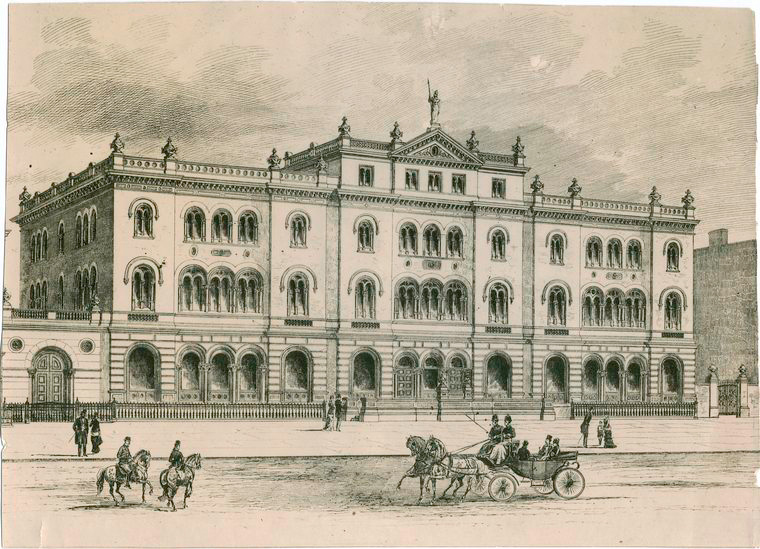

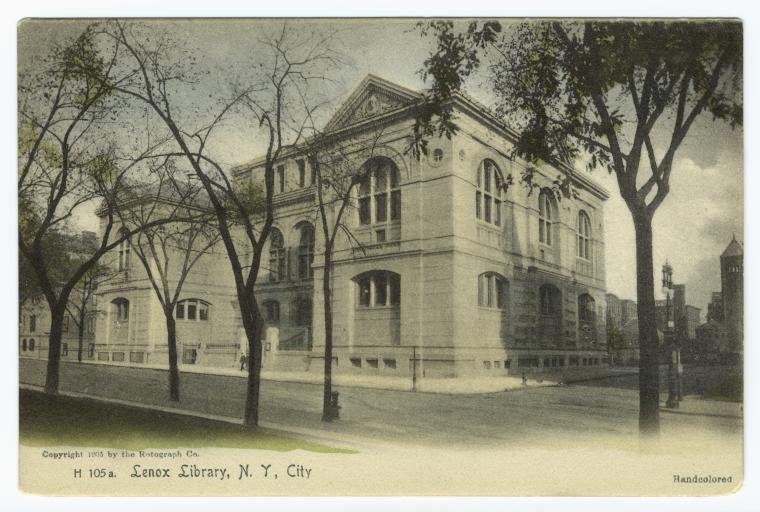

This great institution came into being on May 23, 1895, when "The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations" was established. A year-long centennial celebration for that event was held 16 years ago. The Astor and the Lenox in the new body's name represented two large public reference libraries then existing in the city, whose collections would become the nucleus of the planned new library. The Astor Library had been open on Lafayette Street since 1854 (the building now houses the Public Theater). It was the nation's first large public reference library and New York City's first large free library. It was followed by the more specialized Lenox Library, which opened at Fifth Avenue and 70th Street in 1877, on the lot where the Frick Collection now stands. In 1895, these two libraries together held about 350,000 bound volumes available for on-site consultation only.

These two institutions were gifts to New York from two wealthy men: John Jacob Astor (1763–1848), founder of a legendary fortune, and James Lenox (1800–1880), an important collector of rare books and manuscripts and the importer of the first Gutenberg Bible to land on American soil.

But who was Tilden? And where was his library?

Samuel Jones Tilden (1814–1886) (1, 2, 3) was a former New York governor who had run for U.S. president in 1876. He went down in history as the only man to win the popular vote, but lose the electoral vote. More importantly for our purposes, he died a wealthy bachelor and left the bulk of his estate — rumored to be as much as the then-astronomical sum of 10 million dollars, though it was actually a few million short of that — to a trust to be called the Tilden Trust, whose purpose was "to establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the City of New York," along with his personal book collection comprising some 20,000 volumes.

For various reasons, neither the Astor Library nor the Lenox Library could be considered a truly public library worthy of the metropolis New York City had become by the 1880s. Public demand for such an institution was growing. When Tilden's bequest became known, a dream was born of a "Tilden Library" that might achieve a size and importance until then equaled only by the great national libraries. From The Critic for February 5, 1887:

"This gift to New York, and through New York to the whole world, is one of the largest bequests of the kind recorded in history ... The exact amount of money which the Trustees of the Tilden Library will have under their control is not yet known, but it is not likely to fall short of four million dollars and may largely exceed that sum. Few persons not specially informed in such matters can form any conception of what can be done with the income from such an estate toward the foundation of a library. Its wise expenditure would ensure the building up in a few years of an institution superior in equipment and facilities to any now existing in America, and destined within the lives of living men to rival the British Museum and the Bibliothèque National. There can be no doubt of the need of such a library in this country; there should be no delay in securing it."

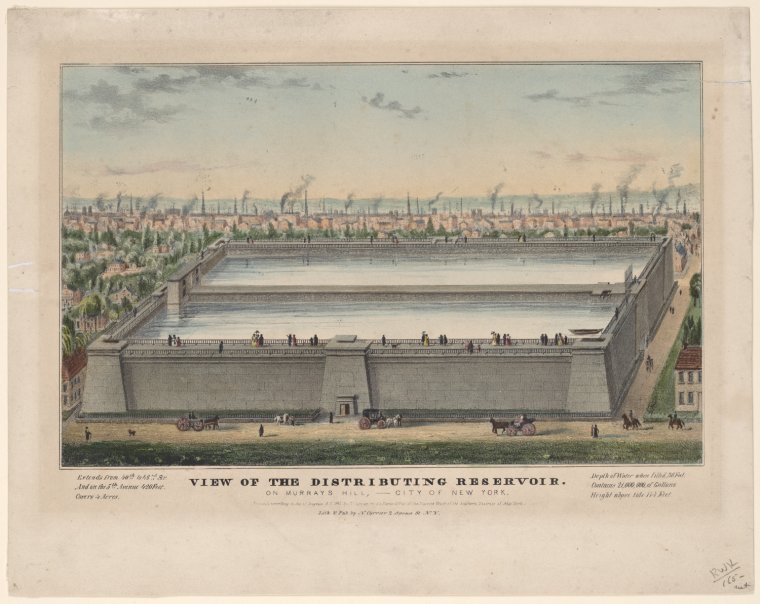

Interestingly, this article already mentions a possible site for such a library, referring to "the suggestion, in some quarters, that the old Reservoir at Fifth Avenue and 40th and 42d Streets should be put at the disposal of the Tilden Trust as the site of the main library building."

Laura P. Hazard, Tilden's grandniece, and her husband William A. Hazard, from a 1921 passport photo. Laura Hazard's generous gesture restored a large portion of Tilden's bequest to the Tilden Trust

Laura P. Hazard, Tilden's grandniece, and her husband William A. Hazard, from a 1921 passport photo. Laura Hazard's generous gesture restored a large portion of Tilden's bequest to the Tilden Trust

That was a lot, but almost certainly not enough, by itself, to fulfill the dream of a Tilden Library that would rival the world's greatest. John Bigelow, Tilden's old friend and political associate, had helped him draft his will and now headed the trust. Despite the change of fortune, he remained an enthusiastic supporter of the "Very Big Library" idea, and he revived a proposal that had first been bandied about in the 1880s: Let the City Fathers cover the expense of constructing the building for the new library, and let it be located on city-owned land, in Bryant Park and on the site of the obsolete Distributing Reservoir that stood beside it. That would free the Tilden Trust funds for operating and staffing the library and purchasing books to expand its collections to be as comprehensive as possible.

Bigelow's article "The Tilden Trust Library: What Shall It Be?" in Scribner's Magazine (September 1892) outlines this proposal in great detail, complete with architectural renderings and floor plans (by Ernest Flagg), for what he called "this library, the manifest destiny of which is to become the most important library of the continent." In his scheme, the library would have sprawled out across the park as well as the reservoir site, though its area would have been less than the space covered by the monolithic reservoir, expanding the available parkland. This article made quite a splash in the press. The New York Times (August 24, 1892) summarized it under the headline "Bryant Park for a Site: Mr. Bigelow's Plan for the Tilden Library." In November of that year, the Trust formally requested that the City of New York should build, and the Trust equip and operate, a library "commensurate with the magnitude and importance of our commercial metropolis."

But negotiations with the city stalled, and the trustees turned to another problem, that of not spreading the reduced Tilden monies thinner than necessary by duplicating the efforts of the various libraries already operating in the city. Several schemes of merger were proposed, including one that would have joined the resources of the Trust with the collections of Columbia College. But the one that made the most sense for all the parties and would best fulfill the spirit of Tilden's will was the one that was eventually adopted. In March 1895, more than two months before the formal consolidation, the news leaked to the press. As the Times reported, "The amalgamation of the Astor and Lenox Libraries and the Tilden Trust Fund and the formation therefrom of a great public library to be known as The New-York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations, became an assured fact yesterday." John Bigelow was named the first president of the new corporation.

The collections of the Astor and Lenox libraries did not circulate. So that the new library could be of the greatest service to the entire population of the city, not just a scholarly and leisured elite, there clearly needed to be a circulating component, preferably in the form of a system of neighborhood libraries. Indeed, if the city were to agree to supply a site for a central building and finance its construction, this would be a practical necessity. New York already possessed the rudiments of such a system in the form of several independent organizations, notably the New York Free Circulating Library (founded in 1878), of which Bigelow was also a trustee, and the Aguilar Free Library (founded in 1886). They too would eventually merge with The New York Public Library, in 1901 and 1903 respectively, and the neighborhood library system would be greatly expanded through the generosity of another plutocrat, Andrew Carnegie. But that is a story for another time. For now, let us return to the problem of where, and how, the central building for the great library would be erected.

The reservoir site was only one of several proposed. But it had several advantages: its central location, for one, and the fact that the obsolete reservoir was on city-owned land for which a use had been sought for decades. Eventually the trustees were agreed on the site, and in March 1896, a formal request was made to the city fathers to approve "such legislation as will enable the City to grant to this Corporation, by some permanent tenure, a proper site for its Library Building and such funds as may be necessary to enable this Corporation to construct and equip its building thereon; and that the site of the present Reservoir on Fifth Avenue, between Fortieth and Forty-second Streets, be granted for that purpose." It took more than a year of lobbying and wrangling, but on May 19, 1897, the final bill was enacted authorizing the city to remove the reservoir and construct and maintain a library building on its site, to be occupied and operated by The New York Public Library.

But nearly five years would elapse before the site could be cleared, and construction on the monumental building occupied another nine. During that time, the Astor Library and the Lenox Library continued to function much as before, maintaining their separate identities, though they were in fact now jointly the repository for the collections of The New York Public Library (Tilden's own collection had been moved to the Lenox building). It's not surprising that we can occasionally find references to the new building as the "Tilden Library." It was well known that the Tilden Trust money was the driving force behind the new institution — it represented a sum more than double than that of the endowments of the Astor and Lenox Libraries combined — and indeed, Tilden's intention to give the city a library to outshine any until then existing in it had been known for two decades by the time construction was well underway. It was also being erected on the very site long associated with the proposed Tilden Library. No wonder the Vernon Howe Bailey drawing of the yet-to-be-completed Main Reading Room was identified as depicting the Tilden Library — though the factual inaccuracy was corrected when it was published in Harper's.

And so, with all due respect to Mr. Schwarzman, in a very real sense the anniversary we are celebrating in this year of 2011 is the centennial of the Samuel J. Tilden Library — the library he and the executors of his will envisioned: "such a Free Public Library in the City of New York" (as it was phrased in the 1887 petition to establish the Tilden Trust) "as would best serve the interests of science and education, and place the best literature of the world within easy reach of every class and condition of people in our commercial metropolis, without money and without price." The building designed to accomplish that end was dedicated on May 23, 1911. The public began streaming in the following day.

The Rose Main Reading Room of The New York Public Library in 2006, by David Iliff

The Rose Main Reading Room of The New York Public Library in 2006, by David Iliff

For further reading:

- Bigelow, John. The Life of Samuel J. Tilden. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1895. Available online via HathiTrust (v. 1, 2).

- Dain, Phyllis. The New York Public Library: A History of Its Founding and Early Years. New York: New York Public Library, 1972.

- Lydenberg, Harry M. History of the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. New York: New York Public Library, 1923. Original version published in the Bulletin of The New York Public Library; available online via Google Books (v. 20, 21, 24, 25) and HathiTrust (v. 21, 24, 25)

- Proceedings at the Opening of the New Library Building, May 23, 1911. New York: The New York Public Library, 1911. Available online via HathiTrust and Google Books.

- Rives, George L, and Charles H. Russell. Book of Charters, Wills, Deeds and Other Official Documents [relating to] The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations . New York: Printed for the Trustees, 1905. Available online via the Internet Archive and Google Books.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Gorgeous! and very

Submitted by dunham (not verified) on August 30, 2011 - 10:13am

The Tilden Library

Submitted by Jim Martin (not verified) on August 31, 2011 - 9:44am

Fascinating

Submitted by Zoe Waldron (not verified) on August 31, 2011 - 12:54pm

Battle Over the Building

Submitted by Michael Miscion... (not verified) on September 3, 2011 - 11:17am

Thank you!

Submitted by Nikki Oldaker (not verified) on March 30, 2012 - 4:57am

great post

Submitted by John Bacon (not verified) on September 9, 2013 - 3:06pm