Musical of the Month

Leslie Stuart and the Pirates of "Florodora"

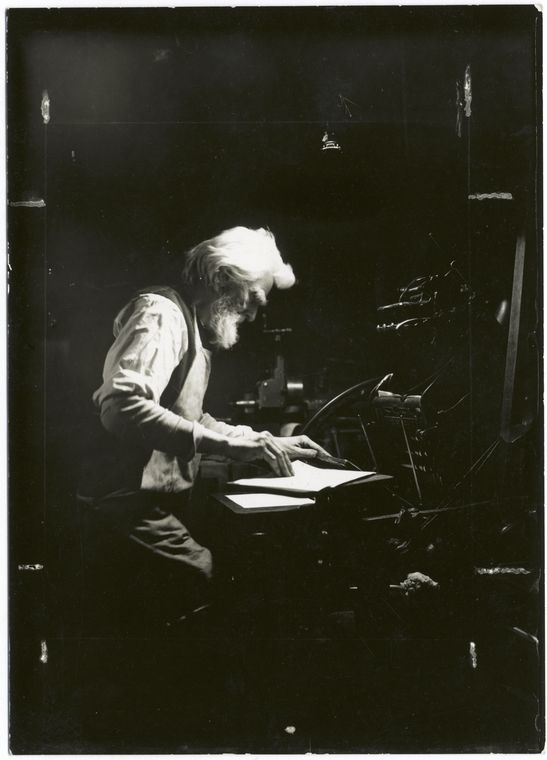

![Tell me pretty maiden, are there any more at home like you? [first line],Tell me pretty maiden / words and music by Leslie Stuart., Digital ID 1947044, New York Public Library Tell me pretty maiden, are there any more at home like you? [first line],Tell me pretty maiden / words and music by Leslie Stuart., Digital ID 1947044, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=1947044&t=w)

It can be easy to assume that the current public conversation over music piracy and copyright law is an entirely new phenomenon, made into a public issue only because of the unprecedented power of the 21st century Internet to transfer large amounts of data quickly and relatively anonymously. In fact, as Andrew Lamb notes in his biography of Leslie Stuart (the composer of Florodora), a similar moment happened in the early days of the 20th century when a drop in the cost of pianos created a demand for cheap sheet music at a time when photographic printing technology had made it possible to quickly and relatively inexpensively produce pirated copies of short publications.

Stuart, a frequently pirated composer, fought against this infringement of his rights for much of his career. In

Lamb proposes that Stuart may have turned to writing for the stage because "royalties for theater performances were so much easier to collect and protect." Stuart was also very particular about how his music was used on the stage (perhaps his run-ins with the pirates had made him especially sensitive to his intellectual property rights). He insisted that any licensed performances use “no less than two verses” of his original version and fought for greater integration of the songs into the plot of the show. Lamb quotes an interview with Stuart that appeared in The Daily Mail in which the composer argued, “In comic opera the song had to be deftly 'worked up to;' in musical comedy plunges are made into the numbers without remorse and without apology.” Although Stuart wrote a popular music of the sort likely to appear in a musical comedy, he desired that his music be integrated into such productions in the way songs are in comic operas, and he had learned the legal mechanisms to insist that his wishes be respected.

A common rationale for intellectual property law is that it encourages innovation and creativity as it offers an incentive to inventors and artists to create. Perversely, though, it may have been piracy that provoked innovation in the case of Stuart. Still, the cost to Stuart should not be overlooked. By 1910, despite having written several international hit musicals as well as many enormously popular songs, Stuart was bankrupt.

In the early 1900s, piracy subsided when publishers finally began to meet the public’s demand for cheaper editions of their music at the same time that the British government passed laws enacting stiffer penalties for copyright infringement. In the 21st century, American society has begun to experiment with the same approaches as services like iTunes, Netflix, and musicnotes.com provide new ways of legitimately purchasing content online at the same time that the American government considers increasingly criminal penalties for copyright infringement. It is an open question, though, whether these approaches, which admittedly seem to have worked a century ago, are the best ways of balancing the rights of artists with the public good today.

I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

NOTE: Summer turns out to be a very busy time for newly installed digital curators of the performing arts. As a result, I'm running a bit behind schedule on the Musical of the Month. Rest assured, though, there will be a new libretto available in the next week or two.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Great article, Doug. I'm

Submitted by Laura Frankos (not verified) on August 5, 2011 - 12:05pm

Great story!

Submitted by Doug (not verified) on August 8, 2011 - 8:40pm