Reader’s Den

The Reader's Den: "A Room with a View" (Week 2) Discussion Questions

E.M. Forster's 1908 novel, A Room with a View, is divided in to two parts: the first takes place in Florence, and the second in England. This week's questions will focus on part one, for those who are reading the book for the first time this month. I have read this book several times, and for me, it improves with each reading. Basically, I'm obsessed with both the book and the Merchant Ivory film adaptation, so please excuse my exuberance! I hope you are enjoying it as well, whether it is your first or your tenth read.

E.M. Forster's 1908 novel, A Room with a View, is divided in to two parts: the first takes place in Florence, and the second in England. This week's questions will focus on part one, for those who are reading the book for the first time this month. I have read this book several times, and for me, it improves with each reading. Basically, I'm obsessed with both the book and the Merchant Ivory film adaptation, so please excuse my exuberance! I hope you are enjoying it as well, whether it is your first or your tenth read.

- Several of Forster's works, like Where Angels Fear to Tread and A Passage to India, focus on the English traveling abroad. In reading the first part of A Room with a View, what allure do you think this subject held for Forster? Do you think he found it easier to show the cracks in English social hierarchies by presenting characters out of their elements?

- Forster reportedly feared that A Room with a View was overly sweet, and even dated, in 1908. How do you think it holds up in 2011? Do you find it could benefit from a little less positivity and maybe a bit more darkness?

- The assortment of characters at the Pensione Bertolini have a little bit of everything — Mr. Beebe with his surprising views (for a clergyman), Eleanor Lavish who views herself as a radical who "revels in shaking off the trammels of respectability," and of course the Emersons. Do you think each character is meant to represent something specific in society?

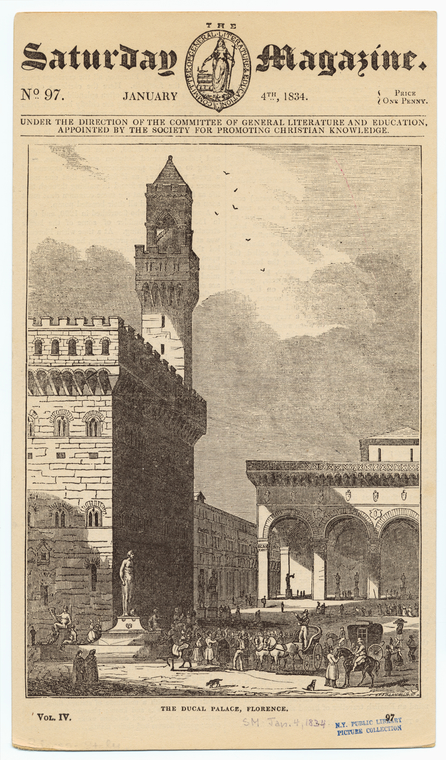

- It is clear that something has passed between Lucy and George after the stabbing in the Piazza della Signoria — "It was not exactly that a man had died; something had happened to the living." Lucy doesn't seem to know exactly what it is, but avoids George until they are thrown together on the day trip to Fiesole and he kisses her. Were Charlotte not with her, how would Lucy have responded to so much intensity? Would she still have needed to escape from George by leaving for Rome or some other destination?

Please respond to these questions in the comments section below! You can also post your own questions or thoughts on characters, themes, or events that I have not touched on here. The next two weeks will have more posts, with more thoughts for discussion about the second section and conclusion of the book.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

English abroad

Submitted by Coleman (not verified) on July 12, 2011 - 12:39pm

Social Constraints

Submitted by Corinne Neary on July 12, 2011 - 4:42pm

Openness

Submitted by Coleman (not verified) on July 13, 2011 - 6:58am

So true, marriages certainly

Submitted by Corinne Neary on July 16, 2011 - 9:08am

I read it. He cheats on her,

Submitted by Coleman (not verified) on July 18, 2011 - 1:23pm

"A View without a Room: Old friends fifty years later," a short

Submitted by Claudine Pepe (not verified) on July 24, 2017 - 10:44am