What's on the Menu?

Maury and the Menu: A Brief History of the Cunard Steamship Company

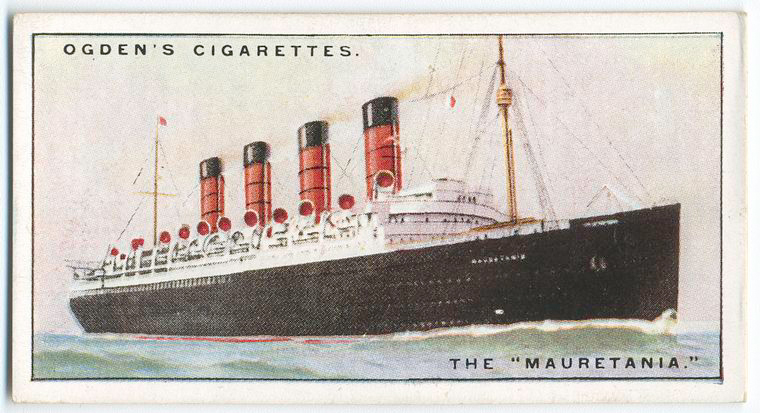

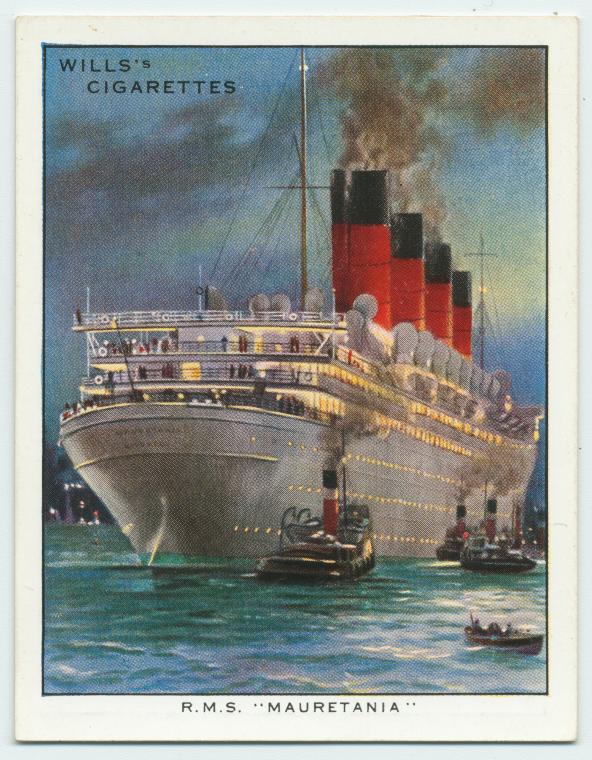

In 1907 the Cunard Steamship Company launched the first of their Express Liners, the Lusitania and the Mauretania, ships that become bywords for speed, luxury and elegance in transatlantic travel. They were the first of the "Grand Hotels" at sea, sister ships each as long as the Capitol Building (and, interestingly, the Houses of Parliament), that came equipped with palm courts, orchestras, a la carte restaurants, electric lifts, telephones, and daily newspapers printed at sea. They were the first big British liners to be powered by four revolutionary Parsons steam turbine engines, and each had a top speed of over 25 knots. Unsurprisingly, both went on to hold the Blue Riband for fastest Atlantic crossing, and the Mauritania held the record for fastest eastbound crossing for nearly 20 years, between 1909 and 1929. Though always reknowned for their safety, Cunard ships did not always have a reputation for carrying passengers in speed and comfort...

![DAILY MENU, LUNCHEON [held by] CUNARD LINE [at] "ON BOARD R.M.S.""MAURETANIA""" (SS;), Digital ID 473125, New York Public Library DAILY MENU, LUNCHEON [held by] CUNARD LINE [at] "ON BOARD R.M.S.""MAURETANIA""" (SS;), Digital ID 473125, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=473125&t=w)

Twenty eight different woods were used to decorate the ship, and furnishings and tapestries were hand made to the height of Edwardian taste. Harold A. Peto, an architect famous for country house interior design work in Britain was hired to oversee decoration. Scientific American described the Dining Saloon as arranged on two levels and decorated in a style known as Francois Premier, with richly carved woodwork and panelling, a "loftily groined dome [...] the crown of which terminates in a gilded convex disk, round which runs a balustrade sheltering hidden electric lights." Beneath the enormous glass dome, chairs and tables were arranged to give diners a good view of their fellow passengers. After their meal, diners could smoke a cigar in the plush, Walnut pannelled First-Class Smoking Room, or relax in the First-Class Lounge. They could order coffee in the very first covered Verandah Cafe, or take a stroll around the the ship's observation deck, situated under the Pilot House and the first to offer protection from the elements.

The Mauretania made her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, November 16th, 1907, and was waved off by a crowd of over 50,000 well wishers. The ship was widely anticipated to break the westbound tranatlantic crossing record set by the Lusitania two weeks before and capture what would informally become known as the Blue Riband. Unfortunately rough weather meant that this did not happen - although the title would be captured two years later - but despite this there was still great interest surrounding the ship's arrival in New York. British and American newspapers covered not only the story of the Mauretania's maiden voyage, but also her commissioning, construction, launch, and speed trials.

With the arrival of the Lusitania - or Lucy - and the Mauretania, Cunard not only reclaimed the Blue Riband, but also cornered the market in luxury and opulence in a way that it had hitherto failed to do.

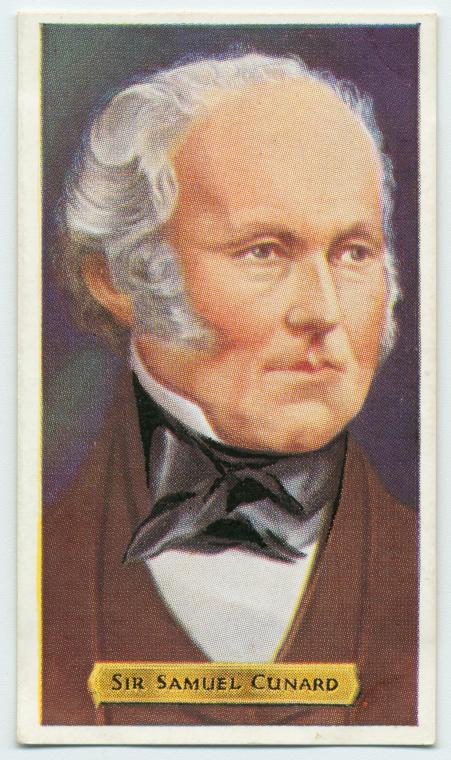

Cunard began life in 1839, as the British and North American Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, created ostensibly to win a contract to ship the Royal Mail from Great Britain to Canada and the United States. The business came to be known as the Cunard Company, after founder Samuel Cunard, a Nova Scotian shipping entrapaneur. Inspired by the revolutionary work of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his "mammoth" steam ship the Great Eastern, Cunard, and his business partners George Burns and David McIver, envisioned a network of Transtlantic shipping lanes along the lines of, and completing links between, railways and roads in Europe and America. He realised that ships powered by steam would not depend upon the wind to get them from A to B, and so could operate on a schedule with the same punctuality as the railroads.

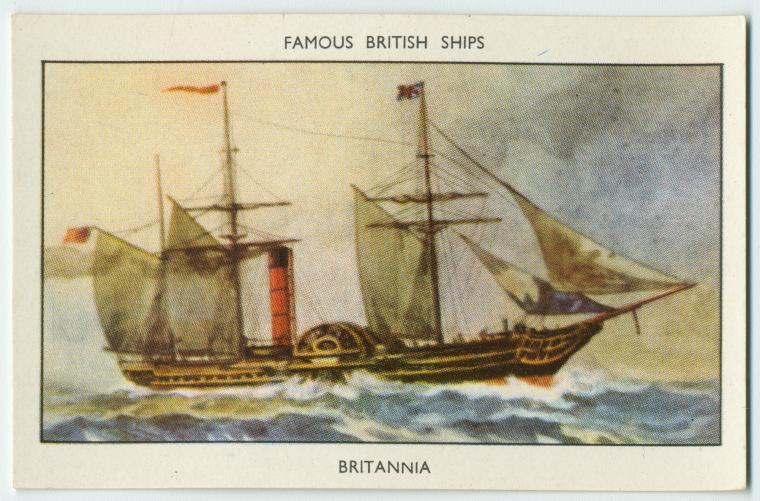

Cunard commissioned the construction of five transatlantic steamers, the first of which was the Britannia. In his book The Cunard Story, historian Howard Johnson describes the Britannia as an inelegant paddle steamer, a "two-decker with one tall orange-red funnel amidships." Launched in 1840, the 207-foot long, 1,145 ton Cunarder made her first voyage July 4th that year, sailing from Liverpool bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia and Boston. On board were 63 passengers (including Cunard and the Bishop of Nova Scotia and his family), 93 crew, Her Majesty's Mail, and one cow: the latter to supply fresh milk. The ship was commanded by one Captain Woodruff, R.N., who barked orders at his crew through a speaking trumpet. When the sea was rough it took as many as four sailors to man the ship's wheel. The steamer completed her journey in 12 days and 12 hours, and would go on to hold the record for the fastest eastbound Atlantic crossing. The same journey by sail could take as much as 35 days.

The image left shows the Britannia in full sail. Sails were seldom used as a method of propulsion, but rather to help stabilize the ship in rough weather. The Royal Navy preferred sail to steam until 1869, and transatlantic steam ships kept their sails until the 1880s: the last Cunard ship to have sails was the Etruria, launched in 1884.

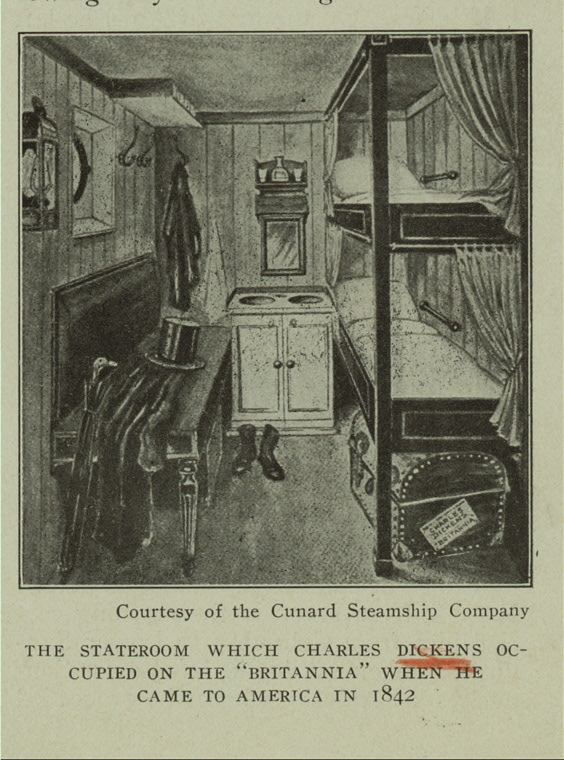

In 1842 Charles Dickens and his wife Catherine were passengers aboard the Britannia. According to the ship's passenger list, they set sail from Liverpool bound for Boston, where the 30 year old author was to begin his first tour of the United States. Dickens wrote about the 18 day voyage in some detail, in the second chapter of American Notes. Seemingly something of a gourmand, he included a description of the food served on ship.

At one, a bell rings, and the stewardess comes down with a steaming dish of baked potatoes, and another of roasted apples; and plates of pig’s face, cold ham, salt beef; or perhaps a smoking mess of rare hot collops [slices of meat]. […] At five, another bell rings, and the stewardess reappears with another dish of potatoes - boiled this time - and store of hot meat of various kinds […] We […] prolong the meal with a rather mouldy desert of apples, grapes, and oranges; and drink our wine and brandy-and-water. The bottles and glasses are still upon the table, and oranges and so forth are rolling about, according to their fancy and the ship's way [...] (26-27)

Conditions aboard early Cunard ships were spartan. The cabins were typically eight by six feet, with two bunks, a hard settee, a commode with two wash basins, two water jugs and two chamber pots. Dicken’s described the saloon, where passenger’s dined, as resembling “a gigantic hearse with […] a melancholy stove, at which three or four chilly stewards [warmed] their hands.” (24)

An unnamed passenger travelling from Boston to Liverpool in 1840, wrote to his father that the food was “carried over open decks [and] sometimes cold, […] fresh food for the first three days and thereafter the fish and meat is salted. Britannia has two ice rooms and the fruit is stored there […] During the journey I counted pea soup nine times and the ubiquitous Sea Pie was on the menu everyday.”

Rules on board ship ordered that "state-rooms (cabins) be swept, and carpets taken out and shaken every morning after breakfast. To be washed once a week if the weather is dry. [...] That bedding be turned over as soon as passengers quit their cabins. That slops be emptied and basins cleaned at the same time. Passengers are requested not to open their scuttles [portholes] when there is a chance of their bedding being wetted. [...] The Wine and Spirits Bar will be opened to passengers at 6 a.m., and closed at 11 p.m."

Though the Britannia did have some luxury furnishings, "carpet's and brocades" for instance, these were removed once a voyage began, as the majority of the rooms, corridors and cabins, were soon awash with sea water, and possessions were often soaked. In addition to this passengers suffering from "mal-de-mer" had a habit of "tainting" the finery once the "vessel commenced to roll." Stewards would tend to sea sick passengers, running from cabin to cabin, issuing rations of brandy to the numerous and unfortunate land lubbers. If passengers could stomach it, the bar was open at 6 a.m. and here diners could order steak with a bottle of hock. The Britannia continued to steam back and forth across the Atlantic until she was sold to the North German Navy in 1849, and renamed Barbarossa. She reputedly ended her days rather ignominiously, as a hulk used for target practice, sunk by the Prussian Navy.

Britannia passenger list 1842, including Charles and Catherine (Mrs.) Dickens.

What early Cunard ships lacked in luxury, or even comfort, they made up for by being safe and reliable. Cunard steamers were well-built, with experienced and reputable captains and crew, initially hand picked by David McIver, himself a former ship's captain. Dickens, despite not having the most pleasurable of journeys, was, once on dry land, full of praise for the ship's captain, one John Hewitt. He addressed captain Hewitt as a man who would live in the memory, and who had returned his passengers to "the pleasure of those homes and firesides from which they once wandered, and which [...] they might never have regained." Between 1840 and the First World War Cunard lost only three ships. Of those, the Columbia (1841), one of the original five Cunarders, was wrecked off the coast of Seal Island, Halifax, and the Oregon (1883) sank in 1886, with no loss of life (or mail) in either case.

![BREAKFAST [held by] NEW YORK & LIVERPOOL U.S. MAIL STEAMER ARCTIC [at] (SS), Digital ID 476899, New York Public Library BREAKFAST [held by] NEW YORK & LIVERPOOL U.S. MAIL STEAMER ARCTIC [at] (SS), Digital ID 476899, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=476899&t=w)

Collins Line ships - notibly the Arctic, Atantic, Pacific and Baltic - were bigger, faster and more luxurious than those of the Cunard fleet, and came with bathrooms, steam-heat, flowered carpets, velvet sofas, and barber shops. The Collins Line was an instant hit, eclipsing the popularity of Cunard, especially as the latter's ships were taken out of service to act as hosptal ships and troop carriers during the Crimean War. The Inman Line introduced two ships, the City of Glasgow and the City of Manchester, both featuring new double iron-screw propulsion, replacing paddles, and freeing up space for more passengers. In 1852 the former was adapted specifically to carry 400 steerage class passengers, the first ship to do so. The Inman Line soon cornered the market in emigrant passengers, and was also a commercial success.

Unfortunately both shipping lines, like many of Cunard's competitors in the mid to late-nineteenth century, were accident-prone. The Collins Line lost the Arctic in 1854, with the loss of 322 lives, including Collins's wife and daughter, and the Pacific, with the loss of 186 lives. The Inman Line was similarly beset with tragedy: between 1854, with the sinking of the City of Glasgow and the loss of 480 lives, a further eight ships were sunk, burnt or wrecked in bad weather. Both companies were heavily hit by these losses and either disappeared or were swallowed up in mergers.

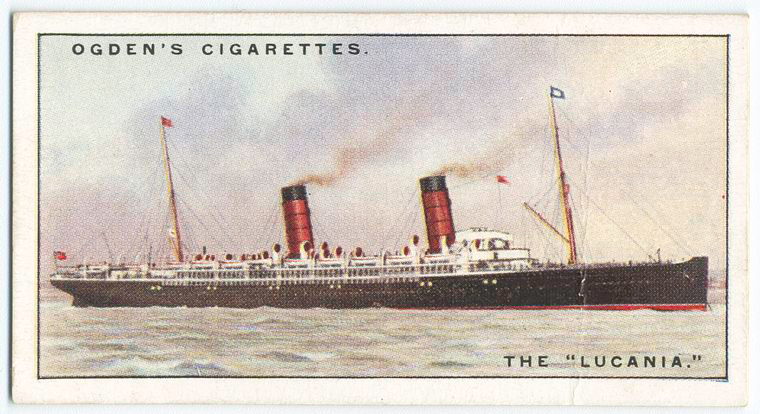

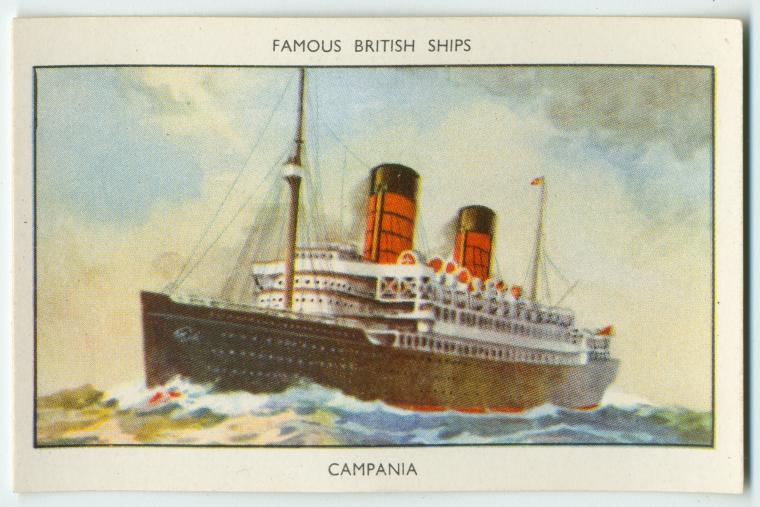

Under pressure from new shipping companies like the White Star Line, Guion, and Norddeutscher Lloyd, Cunard started to focus on offering speed and comfort as well as safety in their passenger liners. The official Cunard web site suggests that "the great international race for supremacy of the North Atlantic" started with the launch of two ships, the Campania and her sister ship, the Lucania, built by the Fairfield Co. Ltd, in Glasgow, and launched in 1893. Each was constructed of steel, weighed 12,950 tonnes, used the latest twin-screw propellors, and had a top speed of 21 knots. They were the biggest and fastest transatlantic ships of their day, carrying 600 First Class, 400 Second Class, and 1000 Third Class passengers.

The Lucania was the first ship to have single berth cabins, and suites (two cabins with a sitting room between them). Each principal room had a fire grate, and the drawing room was decorated with satinwood walls, cedar mouldings, and a ceiling of ivory and guilding. The ship was furnished with Persian carpets, velvet settees and chairs, with brocade, and a grand piano and an American organ. The ladies rooms were scented with freshly cut geraniums, and the Italian-style dining room included Ionic columns and Spanish mahogany walls. First Class passengers could expect to dine on Little Neck Clams, Chicken Okra, Petit Filet de Boeuf ala Parisienne, Timbales a la Richelieu, Roast Qual on Toast a la Monglas, and Neopolitan Ice Cream. Over a breakfast of Broiled Sausages, or Veal Cutlets with Tomato Sauce, passengers could read the very latest news: thanks to onboard experiments by Marconi, the Lucania featured the first ship's newspaper to appear daily with news recieved by wireless.

Despite these advances Cunard still lagged behind her competitors, who continued to build bigger and better ships. Determined to become market leaders once more, Cunard began negotiations with the British government to secure loans to build two massive luxury ocean liners, ones that would capture not only the Blue Riband, but also more passengers. Prime Minister Arthur Balfour gave the go ahead for a state-funded loan to build the Lusitania and the Mauretania, on the proviso that they be constructed to be "convertible to the requirements of the Admiralty as auxillary armed cruisers in time of war." The Lusitania never saw active service: she was sunk by a German U-Boat in 1915, with the loss of 1,198 lives. The Mauretania never became an armed cruiser - she was too big - but spent much of the 1914-18 war transporting troops, most notably 10,000 soldiers to Gallipoli. Later she operated as a hospital ship, finally returning to the North Atantic as a high speed troop carrier, transporting many thousands of US troops to and from the conflict in Europe.

Following the war the Mauretania returned to civilian service, operating between Southampton and New York from 1920 on. Maury became something of a celebrity. In 1922 when the ship returned to the Tyne for a refit thousands of spectators turned out to welcome her home. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man not fond of sea travel, described the ship as having a "soul that you could talk to." Novelist Theodore Dreiser wrote

It was a beautiful thing all told - it's long cherry-wood panelled halls, its heavy porcelain baths, its dainty state rooms fitted with lamps, bureaus, writing desks, wash-stands, closets and the like. [...] the bugler who bugled for dinner! [...] as if to say "This is a very joyous event, ladies and gentlemen. We are all happy; come, come; it is a delightful feast."

The Mauretania was even the inspiration for a song, written by Goodwin and Brown, titled "He's On A Boat That Sailed Last Wednesday (He's Coming Home)." The ship remained Cunard's premier liner for most of the twenties, until 1929, when the Blue Riband was captured by the German liner Bremen. In 1930 the ship's captain opened up the engines and made one last attempt to recapture the record, reaching a creditable 30 knots, but this wasn't quite quick enough. With a new decade the ship's Edwardian fixtures and fittings seemed old fashioned, and so, following a spell cruising the Caribbean, the Mauretania was decommissioned. Steaming past the Tyne and the Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson shipyard, on her way to the breaker's yard in 1935, Maury signalled the men who had built her: "Goodbye, Tyneside. This is my last radio. Closing down for ever. Mauretania." Thousands of people lined the shore, while a flotilla of ships accompanied her on her way, and the assemble crowd sang "Auld Lang Syne." One eye witness reported seeing his father, and dozens of other men like him, who had built the ship, their faces "wet with tears."

Cunard would go on to build bigger, faster and perhaps more famous luxury Express Liners, most notably the ship that was to replace the Mauretania, the Queen Mary, and later the Queen Elizabeth and Queen Elizabeth 2. By the 1950s and 60s, however, with the advent of commercial air travel, the era of the great transatlantic ocean liners was drawing to a close.

Links:

New York Public Library: What's on the Menu?

Tyne and Wear Archives: Mauretania

Search Cunard Ships at the Cunard Heritage web site.

A Selection of images of the interior of the Mauretania, taken from R.M.S. "Lusitania" and "Mauretania" Coronation Booklet, Ed. Deluxe, 1911.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

interior pictures of the mauretania

Submitted by carole mulroy (not verified) on January 17, 2014 - 8:46am

photos of rms mauretania (1)

Submitted by brianburgoyne (not verified) on August 4, 2015 - 12:27am