Biblio File

James Bond, The Brain Stealers, and The Call of the Wild

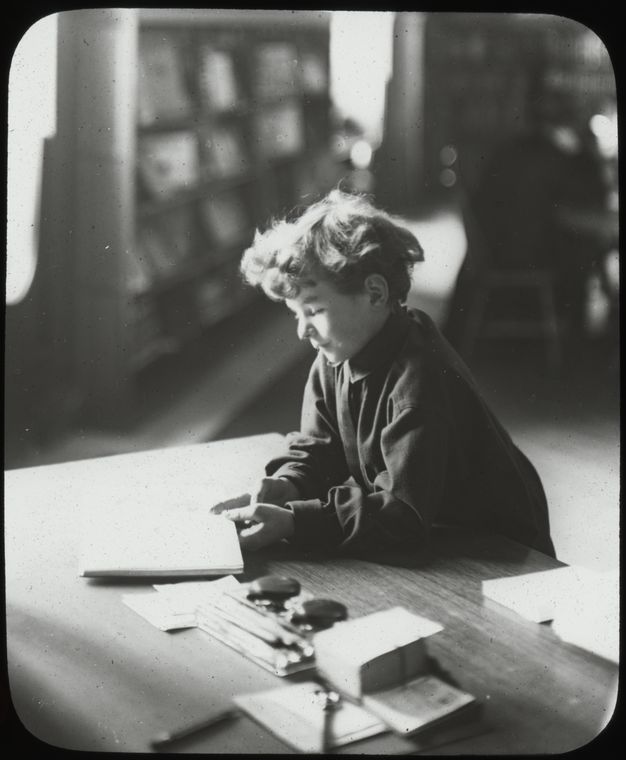

Main Children's Room, 1914Where does your inner voice come from--the chattering that goes on inside your head all day long, well into the night, and on and on for year upon year, sometimes soothing, frequently criticizing, often yearning, forever evaluating? Consciousness is an echo chamber made up of many things, where bits of experience accumulate like sediment, adding layer upon layer. Especially influential, at least from the librarian’s point of view, are the books gobbled up in childhood and the adolescent years.

Many of the books I read in my early days still generate an electrical charge in my brain. In many cases I can summon up from my smorgasbord of memories not only a particular story or the quality of a certain author’s voice, but the physical look and feel of a particular volume as I held it in my hands and feverishly turned the pages. I can remember where I was sitting when I read that book, the circumstances of my life at the time, the quality of light reflecting on the page.

I sometimes imagine the New York Public Library as a vast mansion containing uncountable rooms, and behind many of the doors of these rooms lurk snippets of my own past, waiting to be rediscovered. I have gone back to many old books just to recall who I was when I first read them and what my inner voice might have been whispering to me at the time.

The Library does not have this particular edition (which would have served as my madeleine and probably set me off on a mammoth Proustian blog post), but I did pick up the Library of America Jack London from a shelf of the main reading room to see if I could recapture some of that early magic. The excitement of this adventure story crackles off the first few pages:

“Then the rope tightened mercilessly, while Buck struggled in a fury, his tongue lolling out of his mouth and his great chest panting futilely. Never in all his life had he been so vilely treated, and never in all his life had he been so angry. But his strength ebbed, his eyes glazed, and he knew nothing when the train was flagged and the two men threw him into the baggage car.”

My boyish self responded deeply to the story of Buck, the Sun Valley dog abducted from his cozy existence and sent to the Arctic wastes. This might have been due to having been abducted from a cozy home life of my own and sent to school. A later reading of the same story did not take me very far. There is certainly more to this novel than I at first understood--all sorts of political and social undercurrents run through it, and there is more than a hint of Nietzsche—but, frankly, I am no longer interested in the men who toil for gold or the dogs who make their toiling possible, and time is too short to rekindle too many old enthusiasms.

As time went by, I found myself reading more extensively in these novels, including the mundane bits that connected the sexy bits. I see now that my impulses were not entirely impure: I was trying to learn not only the mechanics of sex but how the grown-up world worked and how adults comported themselves. With the exception of the Mailer, I’m not sure how many (if any) of these books from several decades ago are in print today, but it is reassuring to me that most can still be found (as with the popular fiction of even earlier generations) in the stacks of the New York Public Library.

It is likely that the first step in my life-long library career came with the realization that I liked being surrounded by books. This awareness was spawned in a small used bookstore on Grand Street in Brooklyn. It was the kind of place which no longer seems to exist. There was certainly no barista to make you a latte with skim milk, only walls full of unfinished lumber forming shelves which buckled with the weight of many battered old volumes. Although science fiction no longer has much interest or appeal to me, it was to the science fiction and fantasy paperbacks that I always gravitated, stocking up on cheap books with lurid covers featuring rocket ships, laughably grotesque monsters, and buxom women inevitably dressed in tatters. Silly and pulpy as much of this fiction was, it created a uniquely consuming universe which still percolates fondly in my brain, even if I have no intention of revisiting it.

The name Murray Leinster (pseudonym of William F. Jenkins) might not be familiar to you, but during science fiction’s so-called Golden Age he wrote almost seventy novels and about a thousand stories. Are any of these worth looking up? Frankly, I doubt it, but I was intrigued to find in the library’s catalog a microfilmed collection of seventeen of these ephemeral Leinster paperbacks, boasting titles like The Brain Stealers, S.O. S. from Three Worlds, and The Wailing Asteroid. At the start of The Brain Stealers, an alien space ship has just landed on earth and its curious passengers have ventured forth:

“Presently the moonlight shone upon movement. Upon movements. Creatures in awkward, unaccustomed self-locomotion. They were very small, compared to men, and their appearance was extremely improbable. They hobbled painfully in a compact group. At first they did not communicate even with each other, as if they strained whatever senses they possessed in the effort to savor the nature of this strange planet. Then the thoughts began. They expressed disgust. Disdain.”

Awful stuff, but somehow irresistible. Although it is not likely that I’ll ever find myself sitting in front of a microfilm machine to read these works, I am delighted to have them preserved in this relatively permanent format.

“Commander Bond, or number 007 in the British Secret Service if you prefer it, this is the Question Room, a device of my invention that has the almost inevitable effect of making silent people talk. As you know, this property is highly volcanic. You are now sitting directly above a geyser that throws mud, at a heat of around one thousand degrees Centigrade, a distance of approximately one hundred feet into the air. Your body is now at an elevation of approximately fifty feet directly above its source. I had the whimsical notion to canalize this geyser up a stone funnel above which you now sit. . . .”

When I was finished with each novel, I passed it on to my father, who also doted on them, proving there is no statute of limitations on adolescent fantasy. My interest in Ian Fleming had no doubt been stirred by the early Bond movies, but the realms of fiction and cinema are rarely further apart; the novels are hard little thrillers, with none of the pumped-up special effects gimmickry of the movies. Not long ago, seized with another of those oddball urges to revisit one of the books of my past, I borrowed a copy of You Only Live Twice. This is the one in which Bond goes to Japan on a secret mission, becomes involved with Kissy Suzuki, investigates the Suicide Gardens of Dr. Shatterhand (a bizarre place full of poisonous plants, nasty reptiles, and piranha, meant to encourage people who want to end it all), and ends in a climactic battle with old nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Tossed into the mix, there is even a bit of existential wisdom:

“You only live twice. Once when you are born and once when you look death in the face.”

As I like to imagine myself being slightly more evolved now than I was as an adolescent, I should have walked away from a book containing a character named Kissy Suzuki; but the novel itself is better written than I remembered, the fantastic plot kept me engrossed, and I stayed with it till the end. Beyond that, however, there was nothing. The problem with going back to popular fiction at different stages of your life is that it does not grow with you the way a more literary work will. You might see details unnoticed the first time and even recapture some of the initial excitement, but the novel remains unalterably locked in its own time and place. I have no further need for James Bond.

I suspect that a hot whiff of sentimentality has crept in around the edges of this blog post. Maybe I've spent too much time roaming the back corridors of my reading history and matching what I've found there against the library's holdings. While a good portion of my past is tucked way in our catalog, I've only invoked a small handful of the books which have contributed to the tone and temper of my inner voice.

What are yours?

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

I had the same edition of the

Submitted by JF (not verified) on July 13, 2010 - 4:20pm