Lamenting the Greater Fall: 19th Century Prison Reform and The Women's Prison Association Records

November 27, 1846: "William Haynes, a native of Ireland, has been in this country about two years and six months. He was sent to Blackwells Island three months for selling pernicious books."

December 30, 1846: "John H. Gilman, 41 years old, a native of Vermont, was convicted in this city for forgery in passing counterfeit money and sentenced to Sing Sing for seven years and three months."

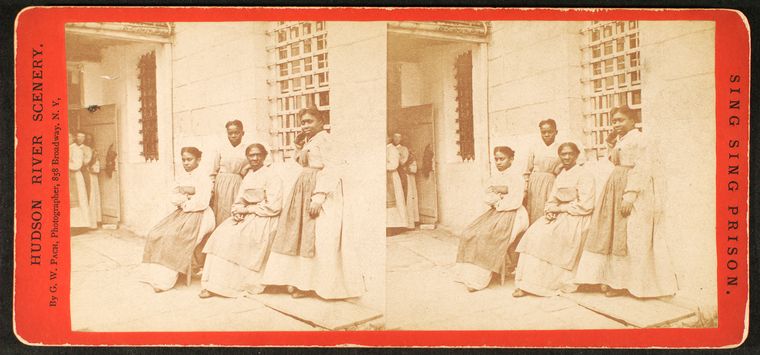

January 22, 1847: "Cecelia Elizabeth Doremus, a native of this City in the eighteenth year of her age was convicted of grand larceny ... and sent to Sing Sing for two years."

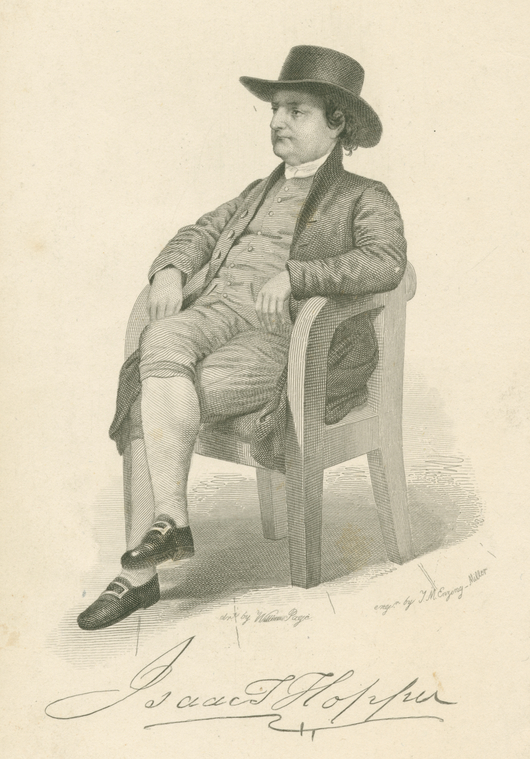

These entries are excerpted from the records of Isaac T. Hopper, and describe the circumstances of

the Prison Association of New York.individuals who sought refuge from New York's penitentiaries and asylums. Hopper was a Quaker abolitionist and notable prison reformer who co-founded the Prison Association of New York (PANY), a mid-19th century advocacy group and resource center for formerly incarcerated persons.

Re-Imagining the Penitentiary

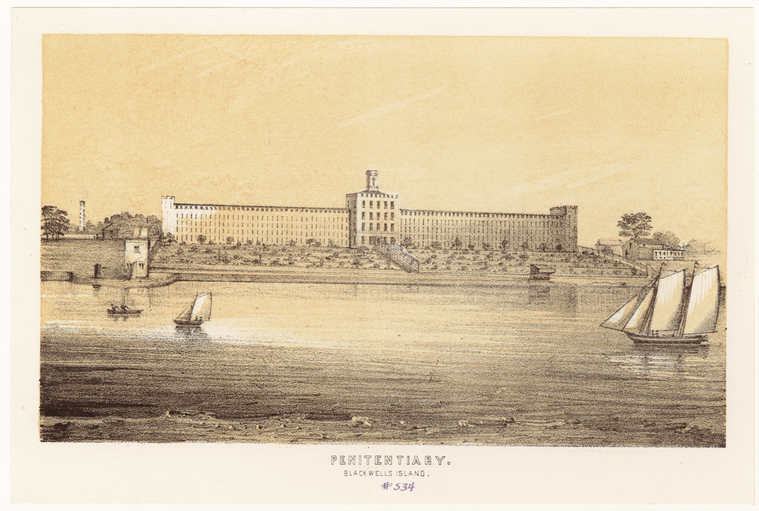

Prior to the PANY's inception, the American penitentiary experienced a revolution of conscience. Reformation of the prisoner's soul, as opposed to punishment of body, became the heart of the early 19th century penitentiary's mission. Newly enlightened prison builders believed improvement of physical health, strict religious observance—even contemplative silence—would help prisoners see the error in their ways, and emerge "changed people." Imposing penitentiaries were built, grand edifices to be the models of American fortitude and modernity. European travellers such as Alexis de Tocqueville and Charles Dickens were among the first eager tourists to view the dazzling structures.

Two popular and opposing methods of prison reform soon emerged: the "Auburn"—or "silent"—system, where prisoners worked together in (surprise!) silent groups throughout the day, and the "Pennsylvania"—or "Separate"—system, where prisoners were kept in constant solitary confinement.

erected 1832, was modeled on the Auburn systemThe infamous Panopticon model—which implied unrelenting surveillance of prisoners—was developed by prison design maven Jeremy Bentham for the Separate system.

Consideration of the merits of each system was a popular source of early 19th century debate, exemplified by this impassioned essay by a Massachusetts man. The participation of average citizens and otherwise apolitical cultural icons, such as authors Caroline Kirkland and Catherine Sedgwick, reveals what a hot topic the prison reform question was, comparable to today's debates over universal healthcare or housing rights issues. Nothing like a squabble over penal reform to get the blood pumping!

Of course, it wasn't long before accusations of prisoner abuse began to marr the reputations of both systems. From reports of Bentham's borderline sadistic torture of inmates to accounts of female inmates' sexual subordination, by the 1830s the American penitentiary was no longer the model for compassionate rehabilitation. It was from these circumstances that the Prison Association of New York and the Women's Prison Association (WPA) arose. The two groups promoted improved prison conditions and provided support for recently released inmates in New York City.

Prison Reform and the Female Inmate

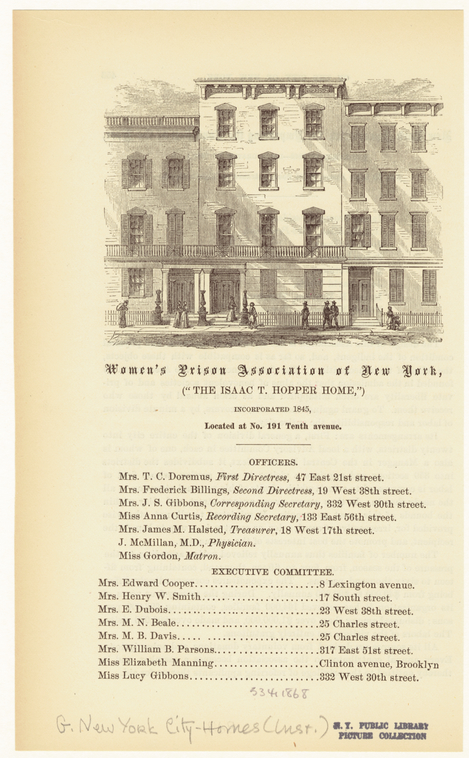

The WPA began as the "Female Department" of the PANY in 1845. The organization attended to the specific needs of incarcerated women, advocating for separate women's prison quarters and female matrons. The WPA also aimed to reform the female convict through strict religious observance and domestic training, as a result of which, they hoped, "the girls" would find plummy jobs as housekeepers, nannies, and seamstresses.

WPA members—many of whom later subscribed to the prim social purity movement—lamented the female convict's "greater fall." They argued these women not only suffered the rule of law, but were also accused of betraying their sex by virtue of their perceived promiscuity while imprisoned.

The 1853 Female Department formally severed itself from the PANY to become the autonomous Women's Prison Association of New York. This separation was due in part, perhaps, to the Female Department's literal belief in the woman's separate sphere. Today, the organization has passed compelling legislation, advocated for the children of imprisoned mothers, and instituted programs supportive of family reunification and alternatives to incarceration. The WPA currently operates three other facilities in addition to the Isaac T. Hopper Home on Second Ave in New York City. NYPL's Manuscripts & Archives Division holds the Association's records.

The WPA records were housed in the basement of the Isaac T. Hopper Home until 1985

The WPA records were housed in the basement of the Isaac T. Hopper Home until 1985

The Records of the WPA

The WPA records consist of correspondence, minutes, reports, legislative bills, project files, client case files, financial records, photographs, and printed matter. The material held in the 148 boxes are in poor condition due both to age and poor storage prior to their accession by the NYPL in 1989. Stored in a damp basement, unfortunately moldy, the records are fragile and access is limited. The client case files contain sensitive personal information, and are restricted to researchers for 70 years from their creation date.  These images show the WPA records as they were transferred from the water-damaged basement to NYPL The best place to begin one's research on the WPA is with the Annual Reports available in the Microforms Reading Room. The reports are a boon to researchers who require clear information about the WPA's history without the insalubrious effects of mold spore inhalation.

These images show the WPA records as they were transferred from the water-damaged basement to NYPL The best place to begin one's research on the WPA is with the Annual Reports available in the Microforms Reading Room. The reports are a boon to researchers who require clear information about the WPA's history without the insalubrious effects of mold spore inhalation.

If I've whet your appetite for further reading on the Women’s Prison Association and 19th century prison reform, check out these titles for suggested further reading:

- Their Sister's Keeper's: Women's Prison Reform in America, 1830-1930

- Partial Justice: Women in State Prisons, 1800-1935

- The Development of American Prisons and Prison Customs 1776-1845: With Special Reference to Early Institutions in the State of New York

- An Account of the State Prison or Penitentiary House, in the City of New York

- With Liberty for Some: 500 Years of Imprisonment in America

- Punishment, Prisons, and Patriarchy: Liberty and Power in the Early American Republic

- From Newgate to Dannemora: The Rise of the Penitentiary in New York, 1796-1848

- The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941

- Benevolent Repression: Social Control and the American Reformatory Prison Movement

- Religion and Development of the American Penal System

- The Prison Reform Movement: Forlorn Hope

- The Hopeful Side of Prison Reform

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

thank you!

Submitted by (not verified) on May 22, 2010 - 2:37pm

I took a couple classes on

Submitted by Patrick (not verified) on May 25, 2010 - 4:03pm

finding aid?

Submitted by Ellen (not verified) on July 13, 2010 - 6:57pm