For symbols of the freedom of the road, you can't beat the wind in your hair, piles of crinkly state road maps at your side, and a whole continent of asphalt spilling out underneath your wheels. The devil-may-care excitement that goes with exploring the American continent has lured many a traveler since the invention of the automobile.

For symbols of the freedom of the road, you can't beat the wind in your hair, piles of crinkly state road maps at your side, and a whole continent of asphalt spilling out underneath your wheels. The devil-may-care excitement that goes with exploring the American continent has lured many a traveler since the invention of the automobile.

But would one ever call taking a road trip a feminist activity? I don’t mean Thelma and Louise on a tear in a Ford Thunderbird, shooting criminals and running from the law. That’s Hollywood. I mean real, adventuresome women out to investigate what there is to see in these United States.

As with any such discussion, the answer to our question hinges on what definition of Feminism one accepts. While there are many faces to the Feminist movement, for our purposes let’s assume that asserting one’s independence to undertake revolutionary acts, flying in the face of gender-based societal disapproval, fits the bill. Using these standards, the authors of two different travelogues published more than 80 years apart would likely agree with us that, yes, putting foot to metal is a feminist act.

In the book Girldrive, published in 2009, authors Nona Willis Aronowitz and Emma Bee Bernstein describe their cross-country travels, during which they interviewed women from coast to coast about whether they subscribe to Feminism, and what exactly it means to them. Aronowitz and Bernstein focused primarily on women of their own age—both are in their early 20s—and attempted to answer a question posed in the media and by many second wavers: why are so few of the younger generations active, self-proclaimed feminists? Interestingly, what they found is that many young women do believe in the movement’s ideas, and are actively involved in a number of related causes. From this standpoint, the book is a must-read for all of those sounding Feminism’s death knell.

The book is also a must-read to discover why those who don’t adhere to the term have rejected it. Many of these women, far from being old-fashioned traditionalists, hold with the beliefs but choose not to identify with the movement. For them, the movement is too “wimpy,” doesn’t address the issues they experience as a racial or religious minority, or feels too constraining and of an alienating scholarly bent. And sadly, Aronowitz and Bernstein also found ample evidence that the movement lost in a branding war before the public arena: the old tropes “feminazi,” “angry, hairy-armpitted lesbian,” and other related concepts make appearances in some of the discussions.

![[Witch And A Black Cat.], Digital ID 834499 , New York Public Library [Witch And A Black Cat.], Digital ID 834499 , New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=834499 &t=w) An ironic depiction of feminists

An ironic depiction of feminists

The most interesting reason for reading Girldrive, however, is that it’s a visually beautiful book full of the images and thoughts of interesting young women across the country. Women are presented from a variety of ethnicities and socio-economic origins, adhering to all manner of religious and political beliefs, and living in the urban centers and the rural corners. The authors talked to riot grrrls on both coasts, plus-size burlesque performers in Texas, community organizers, a transgendered man, artists, authors, hip-hop performers, a physically disabled poetry professor, mothers, college students, abortion clinic workers, and a former member of the military. Each of these women had a unique take on what makes a feminist, for good or bad, giving weight to Bernstein’s musing that, “This is the reason to go on the road. To face the possible falsity of finding one national character."

Ultimately, Aronowitz and Bernstein’s road trip was an eye-opening feminist experience for the authors and the readers both, and while not offering a prescription for unifying the movement, it does move the conversation forward by serving as a sample survey of the younger generation.

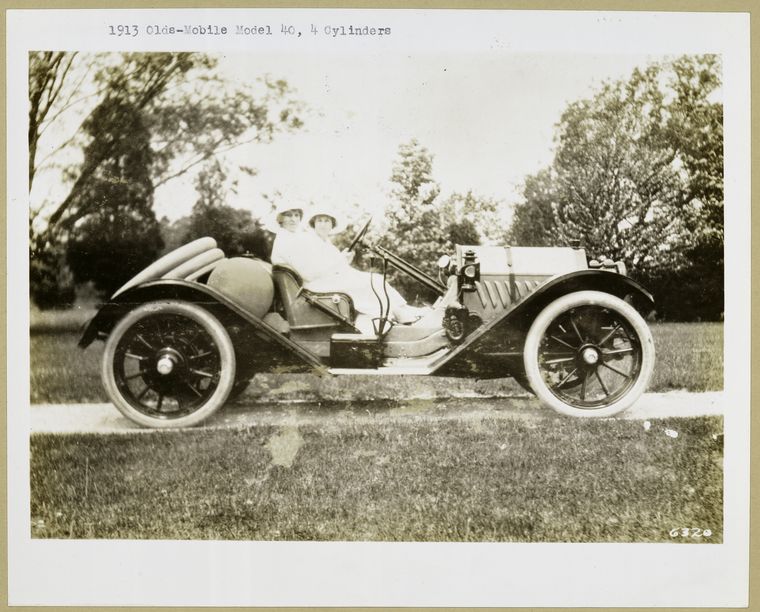

Linking back to an earlier era of lady motorists, the 1928 publication

How’s the Road, is a witty, very readable adventure reliving a 1923 car trip that author Kathryn Hulme took with her best pal Petunia, “Tuny,” across the northern United States. Kathryn and Tuny drove alone at a time when there was no interstate highway system nor reliably asphalted roads, and no system of frequently-spaced rest stops. Mechanics were of unknown quantity and quality, and “nice” women simply did not do such things unescorted. Interestingly, the perception that such a trip wasn’t safe for ladies often played in their favor, when male mechanics’ and others’ chivalrous natures led them to take special care to help the travelers along.

These ladies drove their

roadster “Reggie” from New York to the west coast through the Twin Cities, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, British Columbia, Idaho, and Washington. They then turned southwards and hit Oregon and northern California, ending their 6,000 mile journey in San Francisco. Not ones to end the fun so soon, they next sold the car and took the train back to New York!

Were Kathryn and Tuny conscious of their trip as a feminist activity? Yes and no. While the word itself was never used, and Hulme certainly didn’t analyze their trip from a gender-revolution standpoint, she was certainly aware of the bravery required and was pleased to be doing something so rebellious and adventuresome. For example, on packing for the trip,

"In the door pockets we stuck the things needed for immediate use, including a pistol. There was some parental dispute about the carrying of firearms but we were firm on that point. The illusion of hazard would have been completely destroyed if we had left our gun at home."

And on attempting to find lodging each night,

"As I look back on it now and recall the many women who were approached on some city corner by Tuny and me, and who veiled under a smile of kind sympathy their rank disapproval of two girls hotel-hunting at night, I exult in the flexibility of American mothers."

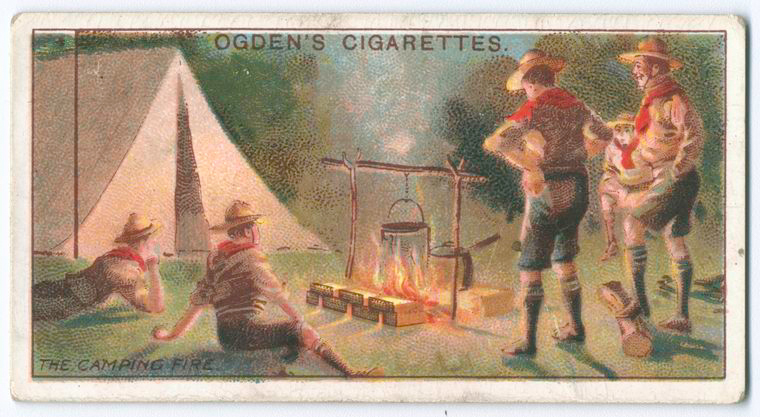

Hulme and Tuny camped in outdoor car camping sites that foreshadowed the Hoovervilles to come, met some cowboys with whom they shared a campfire and breakfast in the South Dakota Badlands, and ignored the advice of a garage man that they shouldn’t try to pass over the Wyoming Big Horn Mountains until July. This last was met by an air kiss blown over the shoulder from Hulme, as Tuny grinningly drove onwards.

Sounds pretty revolutionary to me.

So if a cross-continental car trip was a feminist activity in the 1920s, is a similar trip equally significant today? Judging by the frequency with which young women now hit the road, the number of friends who joined Girldrive’s authors for segments of their travels, and the ease and comfort of travel paired with the increased freedoms modern generations of women enjoy, one could argue that it is not. But traveling the country to take the pulse of the Feminist movement, and then writing a book exposing what you find in all its warts and beauty is most certainly a brave—one could even say feminist—act.

And for curiosity’s sake, I attempted to locate Kathryn Hulme in the U.S. Federal Census. I found a twenty-year-old

Kathryn in San Francisco, California in 1920 (pdf), but it is not clear if this was our gal. If any of our readers know anything about her or the mysterious Petunia, we’d love to hear it!

Subject Headings:

Women automobile drivers—History

Feminism—History—20th century

Women travelers

For symbols of the freedom of the road, you can't beat the wind in your hair, piles of crinkly state road maps at your side, and a whole continent of asphalt spilling out underneath your wheels. The devil-may-care excitement that goes with exploring the American continent has lured many a traveler since the invention of the automobile.

For symbols of the freedom of the road, you can't beat the wind in your hair, piles of crinkly state road maps at your side, and a whole continent of asphalt spilling out underneath your wheels. The devil-may-care excitement that goes with exploring the American continent has lured many a traveler since the invention of the automobile. Hulme and Tuny camped in outdoor car camping sites that foreshadowed the Hoovervilles to come, met some cowboys with whom they shared a campfire and breakfast in the South Dakota Badlands, and ignored the advice of a garage man that they shouldn’t try to pass over the Wyoming Big Horn Mountains until July. This last was met by an air kiss blown over the shoulder from Hulme, as Tuny grinningly drove onwards.

Hulme and Tuny camped in outdoor car camping sites that foreshadowed the Hoovervilles to come, met some cowboys with whom they shared a campfire and breakfast in the South Dakota Badlands, and ignored the advice of a garage man that they shouldn’t try to pass over the Wyoming Big Horn Mountains until July. This last was met by an air kiss blown over the shoulder from Hulme, as Tuny grinningly drove onwards. With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.![[Witch And A Black Cat.], Digital ID 834499 , New York Public Library [Witch And A Black Cat.], Digital ID 834499 , New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=834499 &t=w)

Comments

Alice Ramsey

Submitted by (not verified) on April 9, 2010 - 5:35pm

Alice Ramsey

Submitted by Laura Ruttum on April 10, 2010 - 11:06am