The Battle For Brooklyn, 1776

Many Brooklynites today may not realize that their borough was the scene of the first major battle of the American Revolution in August 1776. The British had gathered a major fleet with over 25,000 men and marshaled their forces on nearby Staten Island. Washington unwisely split his army of almost 20,000 between defending New York City, located in what is today Battery Park area, and Brooklyn.

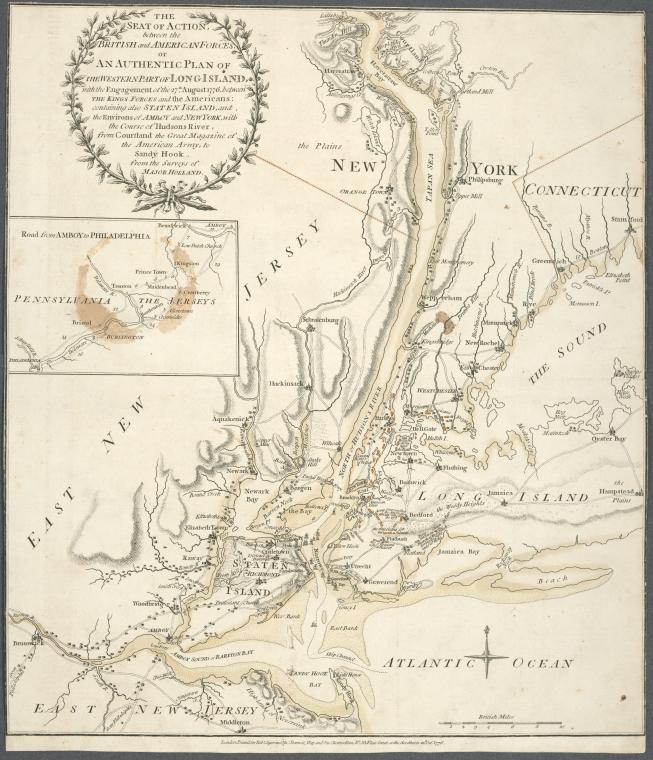

The Heights of Guan, known today as Prospect Heights, were considered key to defending New York. In John Gallagher’s The Battle of Brooklyn, 1776 published by Castle Books, we get a pretty clear picture of the situation. The Battle of Brooklyn, sometimes known as Battle of Long Island as well, was going to be the first major battle of the war. After collecting their forces all summer, the British finally made their move by crossing from Staten Island and landing at Gravesend Bay, Brooklyn. They advanced slowly to what is today Flatbush, and halted.

The main American line was on Brooklyn Heights, with a series of entrenchments and fortifications. In front of this was the heavily wooded area of the Heights of Guan, corresponding roughly to Prospect Park area today. Here the Americans had placed an outer line of defenses under the loose command of Maj-Gen John Sullivan. Today, Sullivan Street in New York’s Greenwich Village is named after him. He was assisted by Israel Putnam, brave, but over his head in commanding anything more than a regiment or two. Alexander Stirling, self styled as Lord Stirling because the British crown had rejected his claim for an earldom, commanded the American Right near the Harbor and the Gowanus swamp. The intent was to slow the British advance, forcing them to fight through rough, wooded terrain, well suited to the tactics of the rebel militia and inexperienced Continental regular soldiers. The problem was that the British were not willing to cooperate in this regard.

General Sir William Howe had gotten bloodied a year early at Bunker Hill just outside Boston. Skilled, but cautious in nature, he knew the Americans could fight well from covered positions. In addition, his subordinate, Sir Henry Clinton had lived in New York some years earlier when his father was royal governor. Clinton knew the Brooklyn area well from his youthful hunting days. He suggested what would become the famous British flanking move that would extend around the American Left by going through Jamaica Pass.

Howe, not fond of Clinton’s over eagerness, still could not deny the genius of the plan. Though the British had superior forces in America, they needed to crush the rebellion as cheaply as possible as their losses could not easily be replaced from Britain. Incredibly, the Americans had neglected to defend the pass, believing it to be too far away. Generals Putnam and Sullivan probably thought the British incapable of doing anything quite so imaginative, and were hopeful of repeating a Bunker Hill-type scenario where lines of redcoats would impale themselves on their strong positions. Washington was hopeful for the same outcome, but the fault lies mainly with him for not taking a more direct command of the situation. The American general was of course inexperienced, as indeed were all his men. This was after all their first major battle as a unified army. Staff work was poor, and responsibilities were not clearly delineated.

On the night of August 27 generals Clinton and Cornwallis lead the main British striking force as it marched in a long circuit around Brooklyn and Queens. This force comprised the best units in the British army including all the Grenadiers and Light Infantry, the Guards, 16th Light Dragoons, the 33rd Foot and 71st Highlanders and several brigades of professional British line regiments. The Light Infantry and Dragoons came through the Jamaica Pass around 2 AM. The small American party posted there was easily captured and all civilians nearby were detained.

Meanwhile additional forces of British and Hessian troops were to decoy and engage the American forces on the Heights by feinting frontal attacks. The whole clever strategy completely fooled the inexperienced Americans who were unaware by the early morning that their entire forward positions were totally compromised. British and Hessian brigades under Grant and Von Heister focused the attention of Sullivan and Putnam to their fronts. The Hessians made a brilliant bayonet charge which carried the position at the Flatbush Pass. Today the area is part of Prospect Park where a plaque called Battle Pass marks the spot. Toward the harbor the British under Grant slowly pushed forward against Stirling’s ad-hoc formation of rebel militia and regulars. Some spirited fighting took place in what is today the general area of Greenwood Cemetery, but the British never intended to press their attack too strongly until they knew the trap was ready.

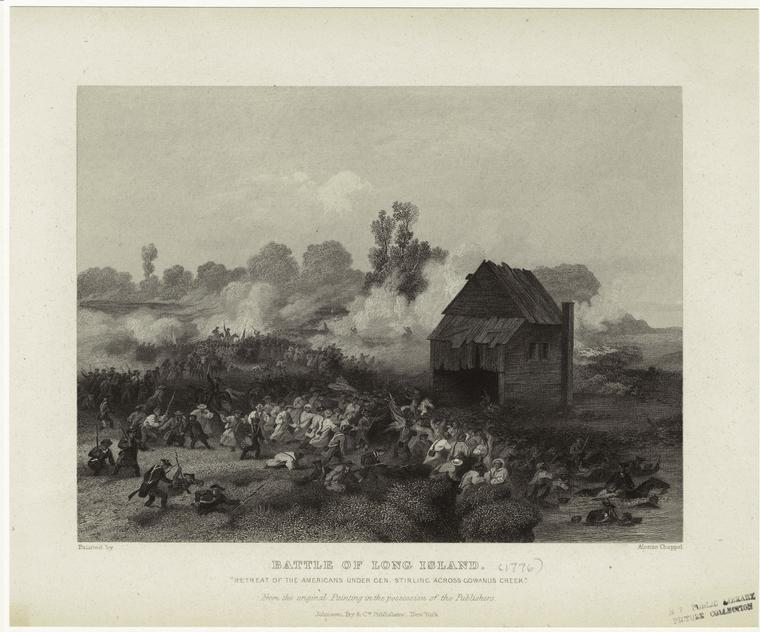

Two booming cannons around 8 AM were the signal to hit the entire American line. This is exactly what happened. Before they knew what was occurring, Sullivan’s and Putnam’s commands were engulfed by British troops. For the most part the Americans just simply ran, although here and there they fought hard. Many were killed and captured when they ran as British and Hessian bayonets took a heavy toll. General Stirling now knew that his position was near hopeless with redcoats in front and behind. His only choice was to try and flee across the Gowanus swamp that separated his men from the main American line on Brooklyn Heights.

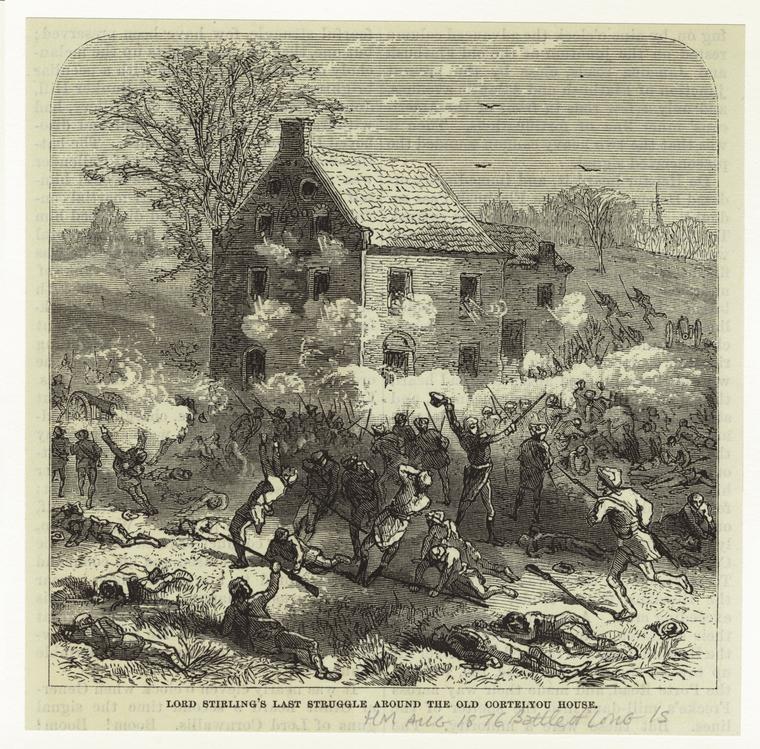

In order to buy time he detached Colonel Smallwood’s Maryland regiment of four hundred men, the best equipped and trained unit in Washington’s army. These gallant men made a noble effort at the Vechte Cortelyou House located just behind the Flatbush Pass. Today it is known as the Stone House where a small museum describes the battle. The Marylanders rushed upon the British many times, their ranks thinned by musketry from the 2nd combined Grenadiers and 71st (Fraser's Highlanders.) Several times they took the house, only to give way because of mounting pressure. Their sacrifice was in vain, with more than 250 of the regiment eventually lost. Still, most of Stirling’s command got away through the swamps, while some were shot down from British artillery posted at the Stone House. A few others drowned. The fight for the stone house was the most intense part of the battle.

By mid-morning the entire forward American line had been collapsed upon the main defenses on Brooklyn Heights. Many of the British, though worn from marching and fighting, were eager to have a go as the Americans were now pinned against New York harbor with no escape. Their troops were shaken from the defeat, and already some of Cornwallis’s Grenadiers and 33rd Foot had actually entered the American works before they were recalled by Howe. Washington’s position on the heights was strong however, and it was this fact that called off the pursuit. Howe, recalling the bloodbath of Bunker Hill, did not wish to repeat the same mistake. He believed the Americans could be taken cheaply by siege, even though it is likely that had the British mounted a determined attack on Brooklyn Heights they could have bagged the entire American Revolution. Many British officers knew that their commander was making a great mistake in not pushing on. For the half days desultory fighting the American had lost in excess of 300 killed and wounded, and over a thousand captured. The British had around 400 casualties.

Some historians try to make the claim that the British loss was actually greater because it included more killed and wounded. This is a false argument. The British may have had more simply because they were attacking against difficult terrain. The American loss may actually have been greater than is often stated, and certainly does not include the scores who deserted after the battle was over. The Battle of Brooklyn was a major calamity for the American cause, even though by European standards of the day it was little more than a skirmish. Had the British been willing to press their advantage the entire conflict could have ended on that sultry August day in 1776. As it was Washington was placed in a desperate situation with his retreat nearly blocked by New York harbor and the Royal Navy. Only bad winds prevented the British from sailing up the East River and totally surrounding him.

Fortunately for the Americans, these adverse winds, combined with bad weather continued for another day, allowing Washington to conduct a masterful retreat over the East River into Manhattan. The battle for New York would continue in the weeks ahead. Still, it had been a close call, and the fault for much of the debacle lay squarely on Washington’s head. It was a painful lesson in the school of generalship. Little remains of the actual battlefield in Brooklyn today, and residents who stroll through Prospect Park, Flatbush and Greenwood Cemetery will come upon a marker here and there that tells of that disastrous day. The New York Public Library has extensive maps and drawings of the battle, a few of which are highlighted here from the digital collection, as well as Gallagher’s book and other works. On this 233rd anniversary of the battle, Brooklyn residents should take note of just how close the American Revolution came to ending right here on their doorstep.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Battle of Brooklyn

Submitted by Aaron Taylor (not verified) on March 15, 2011 - 11:58am

Thanks for your kind

Submitted by Roger (not verified) on April 15, 2011 - 12:19pm

Gerritsen Grist Mill and the battle of Brooklyn

Submitted by Jim Donovan (not verified) on November 6, 2018 - 5:24pm

Battle of Brooklyn blog

Submitted by Joe Bratetich (not verified) on July 12, 2016 - 3:02pm

Battle of Brooklyn, 225th anniversary

Submitted by Bill Lauto (not verified) on August 29, 2016 - 7:10pm

walking in Washington's foot steps

Submitted by Barbara Alfinito (not verified) on June 23, 2017 - 7:07am

The Battle of Brooklyn, 1776

Submitted by Charles Elsden (not verified) on October 24, 2017 - 8:47am

Battle of Brooklyn, 1776

Submitted by Sean Kerr (not verified) on August 3, 2019 - 1:28pm