Biblio File

Let the Wild Rumpus Start! Arthur Rackham and Maurice Sendak

Click images for Catalog entriesLast week in the South Court training rooms, I gave my presentation “Changing Styles in Children’s Literature.” Although I’ve given this talk on various occasions over the last few years, doing it again always focuses my attention on the strange power of children’s books and sets my mind spinning back to my own dim past, when I would stare up at the family shelf of books in a kind of awed yet uncomprehending fascination.

Click images for Catalog entriesLast week in the South Court training rooms, I gave my presentation “Changing Styles in Children’s Literature.” Although I’ve given this talk on various occasions over the last few years, doing it again always focuses my attention on the strange power of children’s books and sets my mind spinning back to my own dim past, when I would stare up at the family shelf of books in a kind of awed yet uncomprehending fascination.

I might not have been aware of much else, but I already knew that those books were the key to some unknown yet highly desirable place. They were full of pictures which created interesting puzzles for me to resolve and indecipherable words which nonetheless buzzed with elusive possibilities.

Scientifically speaking, learning to read is a step-by-step process, each incremental bit building up a solid foundation. In memory, however, it seems much more of a magical transformation. My mother would read the words, I would look at the pictures, and they were always two separate levels of enjoyment. Until a certain memorable day when I began to recognize the actual words myself (something like, “Brontosaurus was a plant-eater”) and suddenly the whole enterprise gelled into one big, amazing package. I would no longer have to make up my own stories to go along with the pictures. And those blocks of text took on a resonance I had never even suspected. In some ways, this process of integrating words and pictures mirrors the two faces of children’s book illustration, particularly during the twentieth century. One the one hand, there are the artists who stress the individual illustration, without too much concern over the accompanying text. On the other hand, there are those who attempt to blend text and image into a richer whole. Throughout my own readings prior to giving my talk, two names kept emerging: Arthur Rackham and Maurice Sendak. They are the two inescapable masters of children’s picture-making, although each seems to represent an opposite end of the spectrum.

This is one of my favorite Rackham illustrations. It depicts a very real prison, with a chain bolted to one wall for shackling prisoners, like something out of The Count of Monte Cristo. You can almost feel the dampness of the stone walls. The comely gaoler’s daughter is attempting to help a prisoner escape by dressing him in the cotton print gown and rusty bonnet of a washerwoman. The peculiar element, as you may have noticed, is that the prisoner is none other than a very literal Toad of Toad Hall, from The Wind in the Willows, whose greatest hope is that he can “leave the prison in some style, and with his reputation for being a desperate and dangerous fellow untarnished.”

This is one of my favorite Rackham illustrations. It depicts a very real prison, with a chain bolted to one wall for shackling prisoners, like something out of The Count of Monte Cristo. You can almost feel the dampness of the stone walls. The comely gaoler’s daughter is attempting to help a prisoner escape by dressing him in the cotton print gown and rusty bonnet of a washerwoman. The peculiar element, as you may have noticed, is that the prisoner is none other than a very literal Toad of Toad Hall, from The Wind in the Willows, whose greatest hope is that he can “leave the prison in some style, and with his reputation for being a desperate and dangerous fellow untarnished.”

In one sense, viewing the works of Arthur Rackham is like excavating the past. He was very much taken with both natural landscapes and the material objects of the world: rugs, fabrics, china, clothing, and furnishings, all of which provided a very literal framework for his fantastic characters and themes. In this scene from the Mad Hatter’s tea party, for example, examine the design of the fine china tea service, the floral fabric of Alice’s armchair, the folds of the linen tablecloth, even the cobbles beneath the table and the thatched roof of the Hatter’s cottage.

This might be Lewis Carroll’s dream-world, but it is very much grounded in the bric-a-brac and minutiae of Edwardian daily life. Although Arthur Rackham’s illustrations detail specific lines or scenes from the work surrounding them, they are also on some level detached from the text, existing very much for their own sake. Rackham does his job, Carroll does his; and while the two might complement one another, they can also exist quite independently. (Incidentally, no online scan ever does these pictures justice. While recent editions of the books might capture the charm and humor of the originals, many generations of low-quality reproduction have made it impossible to recapture their beauty. For the full effect of the winding pen lines and muted water-color washes, a trip to the library to see the first editions is necessary.)

This might be Lewis Carroll’s dream-world, but it is very much grounded in the bric-a-brac and minutiae of Edwardian daily life. Although Arthur Rackham’s illustrations detail specific lines or scenes from the work surrounding them, they are also on some level detached from the text, existing very much for their own sake. Rackham does his job, Carroll does his; and while the two might complement one another, they can also exist quite independently. (Incidentally, no online scan ever does these pictures justice. While recent editions of the books might capture the charm and humor of the originals, many generations of low-quality reproduction have made it impossible to recapture their beauty. For the full effect of the winding pen lines and muted water-color washes, a trip to the library to see the first editions is necessary.)

Like Arthur Rackham, Maurice Sendak has illustrated the work of others; but unlike the British master, Sendak’s principal creations have usually involved both his own words and drawings. His sensibility is thoroughly modern, even if its influences can be found in the past: George Cruikshank, French and German illustrators of the nineteenth century, Randolph Caldecott, Mozart’s music, old comic books, even old movies.

Reading Sendak’s books again, I have the suspicion they have always existed on some sort of personal, subconscious level that lurks beneath the surface, waiting to be tapped into. Two of the most memorable are Where the Wild Things Are and the later In the Night Kitchen. Where the Wild Things Are caused considerable controversy when it won the Caldecott award in 1964.

Critics were upset by the suggestion that a child’s interior life and behavior might be portrayed as so anarchic, so akin to an island full of furry, fearsome monsters. But it’s the truth of this conception that has kept the story alive. As Sendak declared in his Caldecott acceptance speech:

It is my involvement with this inescapable fact of childhood--the awful vulnerability of children and their struggle to make themselves King of all Wild Things--that gives my work whatever truth and passion it may have.

Controversy over Where the Wild Things Are was tame in comparison with the flood of criticism that greeted In the Night Kitchen. When the ultimate history of censorship finally comes to be written, this book will be given a prominent place. Across the country, self-proclaimed arbiters of morality (including teachers and even librarians!!!) were using their black magic markers to draw little black diapers on poor, naked Mickey. Aside from the anatomical correctness of the drawings, the censors also detected a subversive element, a hint of things not generally spoken of in juvenile literature; but children, and most adults who have even the remotest memories of childhood, usually respond to this unspoken something on a gut level. It is like something we all seem to half-remember, poised on the rim of consciousness but not quite touchable.

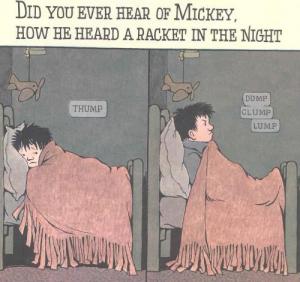

Mickey is awakened in the night by peculiar noises coming from his parent’s bedroom. “Did you ever hear of Mickey, how he heard a racket in the night (thump... dump, clump, lump... bump) and shouted, “Quiet Down There!” As adults, we can hazard a pretty good guess as to what’s going on in that bedroom, but the child Mickey can only slide into a dream food fantasy involving milk and cake batter, all expressive of his unformed and as yet unnamed desires. “I’m in the milk and the milk’s in me,” he sings. “God bless milk and God bless me!”

Please join me for my next presentation “Changing Styles in Children’s Literature” on April 15th at 5pm. I’ll have numerous volumes from the collection on display, including the first edition of Alice in Wonderland from the Rare Book Division. We will discuss Arthur Rackham and Maurice Sendak, as well as numerous other authors and illustrators from the Golden Age of Illustration, including John Tenniel, W. W. Denslow, Howard Pyle, Beatrix Potter, and Jessie Willcox Smith.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

I am also drawn to Sendak's

Submitted by Jessica Cline on March 18, 2009 - 11:09am

I thought about books that

Submitted by Cynthia (not verified) on March 18, 2009 - 12:30pm