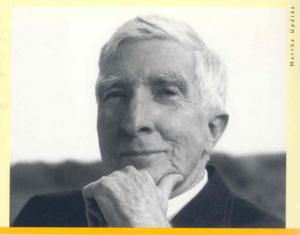

Updike

From the dust jacket of Pigeon Feathers A number of summers ago I saw John Updike at the library. He was sitting in the back of the main reading room, leaning over the table, and writing with a small gold pen. I felt as oddly excited and privileged as someone else might feel who, in the course of day-to-day activity, had encountered Johnny Depp or Angeline Jolie. I ached to know what he was writing on that pad, if it was a story for the New Yorker, another episode in the chronicles of Harry Rabbit Angstrom or Henry Bech, or just a tally of his day’s expenses in New York. I didn’t ask. Library professionalism, New York sang-froid, or maybe just temperamental shyness kept me from saying anything at all. When I looked again a short while later, he was gone.

From the dust jacket of Pigeon Feathers A number of summers ago I saw John Updike at the library. He was sitting in the back of the main reading room, leaning over the table, and writing with a small gold pen. I felt as oddly excited and privileged as someone else might feel who, in the course of day-to-day activity, had encountered Johnny Depp or Angeline Jolie. I ached to know what he was writing on that pad, if it was a story for the New Yorker, another episode in the chronicles of Harry Rabbit Angstrom or Henry Bech, or just a tally of his day’s expenses in New York. I didn’t ask. Library professionalism, New York sang-froid, or maybe just temperamental shyness kept me from saying anything at all. When I looked again a short while later, he was gone.

When I read a few weeks ago that John Updike had died, I was moved on a deep and curious level. It felt as if I had always known his written voice--its shape, style and fluency. My first encounter was with the short story “A&P,” (from the collection Pigeon Feathers) which appeared in a high-school short story anthology. The adolescent Sammy is working at the cash register of the local grocery store when “In walks these three girls in nothing but bathing suits.” My initial interest in the story was perhaps hormonal, based on the vivid description of the eye-catching girl in:

“the plaid green two-piece. She was a chunky kid, with a good tan and a sweet broad soft-looking can with those two crescents of white just under it, where the sun never seems to hit, at the top of the backs of her legs.”

It was the story’s ending, however, with Sammy’s first bitter knowledge of misplaced idealism and disappointment, which brought this teenager dark news of the grown-up world.

I discovered the 1968 novel of suburban adultery, Couples, with its intricate imagery and startlingly precise sexual descriptions, during my early years of college. When the girlfriend I wanted to impress asked to borrow my copy, I had to tell her I couldn’t lend it out just yet because my mother was still reading it. (The girlfriend became my wife, my mother remained resolutely my mother, and Updike was at least one strand which forever bound us.)

Then there was the Rabbit saga, which comprises four novels (Rabbit, Run; Rabbit Redux; Rabbit is Rich; Rabbit at Rest and a novella-length coda, Rabbit Remembered, published in the collection Licks of Love) and is generally regarded as Updike’s masterpiece. Appearing at approximately ten year intervals, these books followed me through my own days, offering a densely imagined tapestry of middle class and middle American values as seen decade by decade, president by president, all activated by the presence of their compelling if morally haphazard main character, Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom. Rabbit at Rest, the final novel in the series and Updike’s Pulitzer Prize winner, takes place, according to the dust jacket, “through the winter, spring, and summer of 1989,” as “Reagan’s debt-ridden, AIDS-plagued America yields to that of George Bush.” It is dismaying to think we’ll have to do without Updike’s take on America under the Obama administration.

Most writers are lucky if their characters give the appearance of life within the fiction that encloses them; only a few can create characters so vital they seem to transcend their pages and lead independent lives. You wonder when the book ends what they might be getting up to next. Harry Angstrom is one such seemingly autonomous character; Henry Bech, the Jewish author who serves (with a good measure of ironic distance) as Updike’s alter-ego, is another. The question of how much of the author is to be found in Bech is addressed in a supposed foreword from Bech himself to John Updike. “Dear John,” it begins.

Most writers are lucky if their characters give the appearance of life within the fiction that encloses them; only a few can create characters so vital they seem to transcend their pages and lead independent lives. You wonder when the book ends what they might be getting up to next. Harry Angstrom is one such seemingly autonomous character; Henry Bech, the Jewish author who serves (with a good measure of ironic distance) as Updike’s alter-ego, is another. The question of how much of the author is to be found in Bech is addressed in a supposed foreword from Bech himself to John Updike. “Dear John,” it begins.

“Well, if you must commit the artistic indecency of writing about a writer, better I suppose about me than about you. Except, reading through these, I wonder if it is me, enough me, purely me.”

After examining his portrayal for the whispers and hints he can detect of other notable Jewish writers, Bech finally perceives, “something Waspish, theological, scared, and insulatingly ironical that derives, my wild surmise is, from you.” My addiction to Updike, coupled with a morbid interest in the literary life, immediately placed these three collections of sharply comic tales (Bech: A Book, Bech is Back, and Bech at Bay) among my favorites.

If my youthful enthusiasm for Updike began with the adolescent characters of “A&P,” it is the aging characters in the collection Licks of Love, viewing their lives from the other end of the spectrum, who interest me now. For example, in “The Women Who Got Away,” the residents of an isolated New Hampshire town who have “survived by clustering together like a ball of snakes in a desert cave,” finally realize that, “you couldn’t sleep with everybody; we were bourgeoisie, responsible, with jobs and children, and affairs demanded energy and extracted wear and tear. We hadn’t learned yet to take the emotion out of sex.” They spend their time ruminating about their marriages and infidelities, mortality and missed opportunities, and try to make sense of what it has all meant.

If my youthful enthusiasm for Updike began with the adolescent characters of “A&P,” it is the aging characters in the collection Licks of Love, viewing their lives from the other end of the spectrum, who interest me now. For example, in “The Women Who Got Away,” the residents of an isolated New Hampshire town who have “survived by clustering together like a ball of snakes in a desert cave,” finally realize that, “you couldn’t sleep with everybody; we were bourgeoisie, responsible, with jobs and children, and affairs demanded energy and extracted wear and tear. We hadn’t learned yet to take the emotion out of sex.” They spend their time ruminating about their marriages and infidelities, mortality and missed opportunities, and try to make sense of what it has all meant.

These are a small handful of choices plucked from a prodigious body of work. Frankly, I don’t hold the same degree of affection for all Updike’s fiction. The African novel, the prehistory of Gertrude and Claudius, the thinly disguised novel about Jackson Pollock, even the popular The Witches of Eastwick were among the books I read with some degree of faltering exuberance. But I have never read anything by Updike which was not contained in rich verbal wrappings, driven by strong narrative propulsion, or laced with an almost uncannily observant artist’s keen perceptions.There are currently 133 items by Updike listed in the catalog of the New York Public Library. How closely that corresponds to the complete Updike is almost impossible to calculate as the number includes many small press publications held by the Rare Book Room of previously published stories or essays, introductions by Updike to the work of others, multiple editions of the same work, the vocal score of an opera based on an Updike novel, even a recording of Updike himself reading from Couples and Pigeon Feathers. We do have the fiction, however, from Poorhouse Fair (1958) to The Widows of Eastwick (2008). The poetry seems to be accounted for, as well as the memoir, the play, children’s books, art essays, and collections of book reviews and assorted prose.

From the dust jacket of Licks of LoveFor the sake of posterity, I’m glad the library reflects so much of this literary legacy. Personally, though, I have never forgotten the afternoon I saw John Updike in the main reading room. Even now, part of me can’t help thinking that he might have been pleased or flattered if I’d offered a small word or gesture of appreciation. Another part wonders if he wouldn’t have transformed me into some librarian sycophant in a Bech story. In either case, it’s too late now.

From the dust jacket of Licks of LoveFor the sake of posterity, I’m glad the library reflects so much of this literary legacy. Personally, though, I have never forgotten the afternoon I saw John Updike in the main reading room. Even now, part of me can’t help thinking that he might have been pleased or flattered if I’d offered a small word or gesture of appreciation. Another part wonders if he wouldn’t have transformed me into some librarian sycophant in a Bech story. In either case, it’s too late now.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

A wonderful homage to

Submitted by JF (not verified) on February 11, 2009 - 4:24pm

I once had a retired pastor

Submitted by Anonymous (not verified) on March 9, 2009 - 12:58pm

Your mention of Updike's

Submitted by Mike Blatty (not verified) on March 16, 2009 - 6:54pm