At Home In Staten Island: A Tale of Two Literary Englishmen and Their Children

Charles Dickens & Charles Dickens Jr., Charles Mackay & Marie Corelli

AT HOME IN STATEN ISLAND.

[For the proper understanding of the following

verses, written by a home-sick Englishman while

resident in Staten Island, near New York, it may

be necessary to state that in North America there

are neither daisies, nor primroses, nor skylarks, nor

nightingales, nor any bird with a musical note except

the mocking bird, which is not often heard north

of Maryland. The "dogwood" and the "catalpa,"

of which mention is made, are flowering trees of

great beauty in the vernal landscape.]

_____________________________________

My true love clasped me by the hand,

And from our garden alley,

Looked o'er the landscape seamed with sea,

And rich with hill and valley.

And said, "We've found a pleasant place

As fair as thine and my land,

A calm abode, a flowery home

In sunny Staten Island .

"Behind us lies the teeming town

With lust of gold grown frantic ;

Before us glitters o'er the bay,

The peaceable Atlantic .

We hear the murmur of the sea —

A monotone of sadness,

But not a whisper of the crowd,

Or echo of its madness.

"See how the dogwood sheds its bloom

Through all the greenwood mazes,

As white as the untrodden snow

That hides in shady places.

See how the fair catalpa spreads

Its azure flowers in masses,

Bell-shaped, as if to woo the wind

To ring them as it passes.

"See stretching o'er the green hill side,

The haunt of cooing turtle,

The clambering vine, the branching elm,

The maple and the myrtle,

The undergrowth of flowers and fern

In many-tinted lustre,

And parasites that climb or creep,

And droop, and twist, and cluster.

"Behold the gorgeous butterflies

That in the sunshine glitter,

The bluebird, oriole, and wren

That dart and float and twitter:

And humming birds that peer like bees

In stamen and in pistil,

And, over all, the bright blue sky

Translucent as a crystal.

"The air is balmy, not too warm,

And all the landscape sunny

Seems, like the Hebrew Paradise,

To flow with milk and honey.

Here let us rest, a little while —

Not rich enough to buy land,

And pass a summer well content

In bowery Staten Island ."

" A little while," I made reply

" A little while — one summer:

For, pleasant though the land may be

To any fresh new comer,

I miss the primrose in the dell,

The blue-bell in the wild wood,

And daisy glinting through the grass,

The comrade of my childhood.

" I miss the ivy on the wall,

The grey church in the meadow,

The fragrant hawthorn in the lanes,

And all the beechen shadow.

And more than all that proves to me

It never can be my land,

I miss the music of the groves

In leafy Staten Island.

" There's not a bird in glen or shaw

That has a note worth hearing ;

Unvocal all as barn-door fowls,

Or land-rails in the clearing.

Give me the skylark far aloft To heaven up-singing, soaring ;

Or nightingale, at close of day,

Lamenting but adoring !

" Give me the throstle on the bough,

The blackbird and the linnet,

Or any bird that sings a song

As if its heart were in it.

And not your birds of gaudier plume,

That you can see a mile hence,

And only need, to be admired,

The priceless charm of silence.

" There's drone, I grant, of wasps and bees,

And sanguinary hornets,

That blow their trumps as loud and shrill

As regimental cornets.

And all night long the bull-frogs croak

With melancholy crooning,

Like large bass-viols out of gear,

And tortured in the tuning.

" And then those nimble poisonous fiends,

The insatiable mosquitoes

That come in armies noon and night,

To plague, if not to eat us.

The devil well deserves his name,*

That sent them to the dry land ;

Let us away across the sea,

Far, far from Staten Island !"

" Ah, well !" my true love said and smiled, " There's shade to every glory ;

There's no true paradise on earth

Except in song or story.

The place is fair, and while thou'rt here,

Thy land shall still be my land,

And all the Eden earth affords

Be ours in Staten Island ."

___________________

*Beelzebub, the lord of the flies

All The Year Round is where the public first got to read A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations . Mingled among that company it’s not surprising that AT HOME IN STATEN ISLAND has received little attention. AT HOME is not listed in any bibliographies of Dickens own works and none of his biographies mention a visit to Staten Island. One year prior to the publication of AT HOME Dickens had visited New York City on his second United States reading tour.

Dickens closest confirmed encounter with Staten Island is described in Charles Dickens as I knew him : the story of the reading tours in Great Britain and America, 1866-1870 by George Dolby. Dickens was departing New York aboard the Liverpool-bound Cunard steamship Russia “which had steamed down the bay, and was lying at her moorings, off Staten Island, awaiting mails and passengers...”

The day was April 22, 1868. Dickens writes in the Uncommercial Traveller :

"It was high noon on a most brilliant day in April, and the beautiful bay was glorious and glowing. Full many a time, on shore there, had I seen the snow come down, down, down … But a bright sun and a clear sky had melted the snow in the great crucible of nature; and it had been poured out again that morning over sea and land, transformed into myriads of gold and silver sparkles.

The ship was fragrant with flowers…such gorgeous farewells in flowers had come on board, that the small officer`s cabin on deck, which I tenanted, bloomed over into the adjacent scuppers, and banks of other flowers that it couldn't hold made a garden of the unoccupied tables in the passengers` saloon. These delicious scents of the shore, mingling with the fresh airs of the sea, made the atmosphere a dreamy, an enchanting one."

"It was my privilege, many years ago, to clasp the hand of Charles Dickens and to hear from his lips the cordial assurance of his personal regard. " If you come to England," he said, " be sure to come to me; and it won't be my fault if you don't have a good time." The great novelist said those words as we sat together aboard a little tug-boat, on the morning of April 22, 1868, steaming to the Russia, which was anchored in the bay of New York, and about to sail for England."

They travelled together through Manhattan by carriage to the tug:

"It was a lovely morning. The air was genial, the broad expanse of the Hudson and the bay sparkled in brilliant sunlight, and the whole silver scene was vital with motion and cheerful sound. .. When Dickens alighted from the carriage and glanced at the river he uttered the joyous exclamation: " That's home! " We were soon aboard the tugboat, — called "The Only Son," — and as we sailed down the river it pleased the novelist to talk with me about many things. I had heard all his Readings in New York, and had written about them, and on that subject he had many pleasant words to say.

The man was with us, unsophisticated and unadorned. He wore a rough travelling suit and a soft felt hat; his right foot was wrapped in black silk, for he had been suffering from gout; and he carried a plain stick. After he had boarded the steamship, and while he was talking with the captain and other officers, the members of our little party assembled in the saloon with what he afterward jocosely described as " bitter beer intentions." Soon he approached our group and, addressing me, he said : " What are you drinking? " I named the fluid, and, responding to his request, filled a tumbler for him. He shook hands with us, all around, with a grasp of iron, emptied his glass, put it on the table, and turned to greet the old statesman Thurlow Weed, who had just then arrived: whereupon, immediately, I seized that glass, and, to the consternation of the attendant steward, put it into my pocket, — mentioning, as I did so, Sir Walter Scott's appropriation of the glass of King George IV, at the civic feast in Edinburgh, long ago. The royal souvenir, it is recorded, fared ill, for Sir Walter sat upon it and broke it. The Dickens souvenir survives and is still in my possession. When the farewells had been spoken and we had left the ship, Dickens stood at the rail, his brilliant eyes (and surely no eyes more brilliant were ever seen) suffused with tears, and, placing his hat on the end of his stick, he waved it to us till distance had hidden him from view. I never saw him again."

There is a vague reference to Charles Dickens actually visiting Staten Island published in Staten Island And Its People (1929, Vol. 1, p. 253) by William T. Davis and Charles W. Leng. It says only “[Charles Gilbert] Hine…adds Charles Dickens to the distinguished list of [Staten Island] visitors.” Leng and Davis don’t say whether it was on Dickens first or second visit to the US. Their source, Hine, is the co-author of Legends, Stories, and Folklore of Old Staten Island (with William T. Davis, 1925) and several other local histories of Staten Island. There doesn't seem to be any existing record of where Hine may have published an account of a Dickens visit or what his source for the information might have been. It could have come from the account of the Russia being moored off Staten Island or just been an assumption that the "home-sick Englishman" in Dickens' publication was Dickens himself. One more possibility is that the reference refers to a visit paid to William Winter by Charles Dickens' son Charles Culliford Boz Dickens or simply Charles Dickens Jr. (1837-1896) Winter lived on Fort Hill in Staten Island's New Brighton neighborhood. Winter wrote: "On one occasion of exceptional and peculiar interest, when Charles Dickens, the younger, dined with us in our home, March 3, 1883...[The tumbler] was placed in his hands, and thus, after the lapse of fifteen years, the farewell glass of the illustrious father was touched by the lips of the reverent and honored son. "

Charles Jr., one of ten Dickens children, served as an assistant editor of All The Year Round under his father and became the editor upon his death in 1870. Much later, in December 2005, Gerald Charles Dickens (1963-), the author's great-great-grandson and an impersonator of his famous ancestor, also made an appearance on Staten Island as part of "DickensFest" at Snug Harbor Cultural Center. Staten Island seems to be a destination for the Dickens family, anyway. Sadly, there doesn't seem to be any record of what happened to the farewell tumbler.

There doesn't seem to be any verifiable record that Dickens visited Staten Island or that he wrote AT HOME IN STATEN ISLAND. Fortunately, the name of the poet is revealed in a reprint of AT HOME in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's book called Poems of Place (1886). The collection features poems based on geographic locations around the world. Poems of Place identifies the home-sick Englishman as Charles Mackay (1814-1889). He was actually born a Scotsman but lived most of his life in England. Charles Mackay was a friend of Dickens. They had worked together on the staff of the Morning Chronicle in the 1830s when Mackay was the editor and Dickens was a new writer just beginning his career. There doesn't appear to be any correspondence between Dickens and Mackay while he was on Staten Island from February 1862- December 1865. It seems likely that he wrote the poem during his stay and did not submit it for a few years but it could have also been written later based on his memory. By the time of publication of AT HOME in 1869 their correspondence had resumed, mainly brief notes about books and works for All The Year Round. In August of 1868 Dickens expressed thanks to Mackay for his "congratulations" apparently referring to his return to England from New York. AT HOME doesn't seem to be mentioned in his surviving letters.

Mackay was a noted poet, journalist and the author of a book that's considered a classic in its field, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841). Much of the book deals with economic bubbles. Today, we may think of dot com or sub-prime mortgage bubbles. He focused on historical bubbles like "Tulipomania", the tulip bulb bubble of 1637. He summed up his thesis this way: "Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one!" Another take on the subject can be found in James Surowiecki's recent bestseller The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations (2004). The investment broker Charles Schwab sides with Mackay: "I consider Extraordinary Popular Delusions... a must-read not only for all investors - but for all thinking people. As Charles Mackay's classic so clearly demonstrates, follow the herd and you may just be headed straight for the slaughterhouse." NY Times best selling author Michael Lewis includes Extraordinary Popular Delusions as one of his six all-time best books on economics in The Real Price of Everything (2008). Several of Mackay's poems, including "Cheer Boys Cheer" and "The Good Time Coming" , were set to music by his friend Henry Russell and became hit songs around 1850, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. He published Life And Liberty in America about a tour he made in 1859.

It was in August of 1862 that Thomas A. DeVyr, a pro-British Irishman, showed Mackay a letter he had received from an unfamiliar organization called the "Fenians". Curious about the origins of the letter, Mackay decided to investigate. Out of concern for DeVyr's safety, Mackay enlisted the aid of an anonymous person from the Courier des Etats Unis, a French newspaper in New York City. He reasoned that someone from a nation so often at odds with Britain, would be above suspicion. The deception succeeded and Mackay exposed the Fenians' operations in the Times of London. Mackay's former paper, the Illustrated London News, reported:

"The New York correspondent of the Times (Mackay) states that the Fenians are remarkably active in the northern States, and that large funds are being collected and sent to Ireland, or expended in the purchase of arms....The day has been fixed for the establishment of a provisional government: 200,000 men are sworn to sustain it; the American and Irish officers who have joined the movement are silently making their way into Ireland; and operations are to be inaugurated sooner, much sooner, than any of you can believe. Each steamer on her arrival at Queenstown from New York or Boston is boarded by the police, who, as a telegram states, search the passengers' luggage for arms or treasonable documents."

However, the exposé had little effect in the U..S. The federal government largely ignored (or possibly encouraged) the actions of the Fenians as a reprisal for Britsh support for the Confederacy.

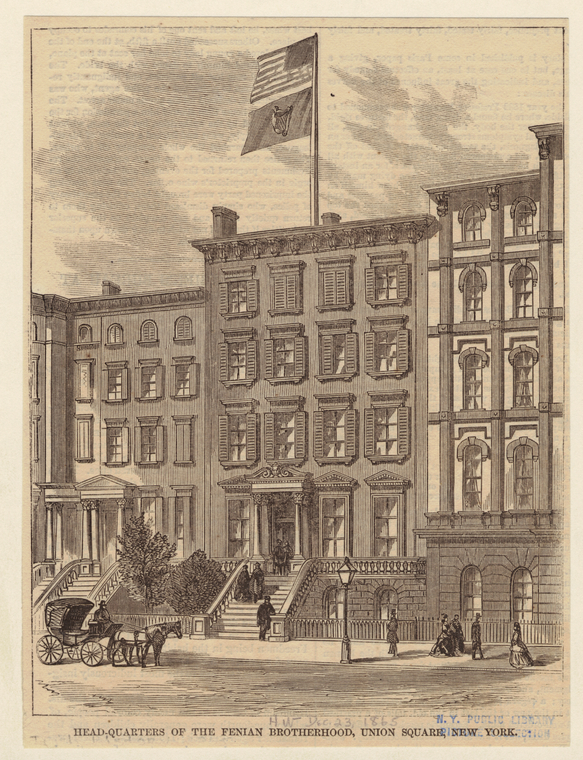

Union Square, New York (1865)The growth of the Fenian Brotherhood led to some curious, and now largely forgotten, events in U.S. history. The first was an invasion of Canada. In 1865 the Illustrated London News warned of the Fenian threat: "Great alarm prevails in Canada as to the Fenian projects. The Fenians had threatened a rising there, and, it was said, had a steamer ready for offensive purposes." On May 31, 1866 a Fenian army of 800 to 1,500 men, mainly Irish-American Union Army veterans, swarmed across the border from Buffalo. Their "Secretary of War" was General Thomas W. Sweeny, a hero of the Battle of Shiloh on temporary leave from the U.S. Army and they were commanded by Colonel John O'Neill. Their aim was to hold the Canadian transportation system hostage in exchange for Irish independence. The Fenians briefly captured Fort Erie in Ontario before United States forces intervened, cutting off their reinforcements and supply lines. Most of the Fenians were given free railroad tickets home by the U.S. government and were allowed to keep their weapons. Sweeny was briefly detained before being reinstated as a U.S. Army General. Smaller raids across the border were launched from Vermont, Maine, and Minnesota. The Fenians also sent the ship "Erin's Hope" from the East River to Ireland bearing a large supply of weapons in 1867. The NYPL Digital Gallery has a collection of portraits of Irish and Irish-American Fenians from Mountjoy Prison in Dublin.

The Fenian Ram with a one-man test model in the foreground in the Paterson Museum.

The Fenian Ram with a one-man test model in the foreground in the Paterson Museum.

Eventually the Fenians would build a weapon that could have easily destroyed any ship afloat. They had their own submarine. It was launched in New York Harbor in 1881, more than a decade before the U.S. Navy had its first submarine. With hopes of attacking British shipping the Fenians hired John Holland, now called "the father of the modern submarine", to build a craft that looks like something Jules Verne might have dreamed up. The Fenians were unable to keep their secret weapon secret for long. The sight of a 31 foot long submarine diving and surfacing in the harbor and lower bay soon attracted the attention of the press. The papers dubbed it "The Fenian Ram". The sight of the sub off Stapleton, Staten Island scared the captain of the paddle wheel ferry St. Johns so much that he turned his boat around and headed back to shore. The Fenian Ram reached its greatest depth, 60 feet, off Stapleton and remained there for more than two hours. It carried a crew of 3, weighed 19 tons and had an 11 foot pneumatic gun designed by John Ericson, builder of the Union's first iron-clad ship, Monitor.

The Ram never saw battle. A splinter group of the Fenians, upset over a payment dispute, used a tug boat and a fake pass forged with Holland's signature to tow the Ram away, along with another one-ton test sub, from the Morris Canal in Jersey City. All went well until the tug reached the site of the present-day Whitestone Bridge where an open hatch on the test sub flooded and it sank. The Ram was towed on to New Haven but the Fenians were unable to operate it. The harbor master declared it a hazard and prohibited its further use. Holland knew the sub was inoperable without his expertise and declared "I'll let her rot in their hands". The Ram did eventually perform one mission for the Fenians- as a fundraising exhibit in Madison Square Garden in 1916. The Fenian Ram can still be seen today in Paterson, New Jersey, Holland's hometown, at the Paterson Museum.

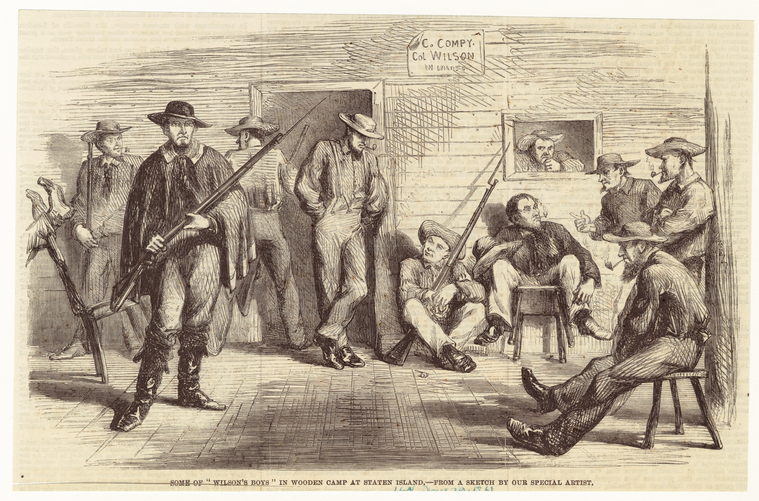

As a foreigner, who expressed reservations about the Northern cause in time of war Mackay angered lots of people. Mackay wrote that the editor of the Herald, James Gordon Bennett Sr., "went so far as to hint to the soldiers of Camp Scott on Staten Island, near to which I resided ...that it might be a just punishment to burn my house over my head." Camp Scott was a federal army camp in the present "Old Town" neighborhood. According to Mackay the animosity started because the Times of London had misquoted him as calling both the North and South "cowards" in the Civil War .

There is another mention of a fictional Englishman on Staten Island in All the Year Round. Again, no author is listed but it expresses sentiments similar to Mackay's and it is possible that Mackay is the author of this story in the January 23, 1864 edition:

ADVENTURES OF A FEDERAL RECRUIT.

"As an Englishman, travelling through the State of New York… possessing only the clothes I then stood in, and some three dollars, in American notes… What could I do? I was reckless; I was disheartened... I was in a guard-house on Staten Island. How or why I came to be there, I knew not... "

The story is about an Englishman who is drugged and imprisoned at Camp Scott by members of an Irish Brigade who berate him with anti-English insults while pressuring him to enlist. After six weeks he escapes through a barrage of bullets fired by the camp guards. He's shot but runs blindly in the darkness until he reaches the Port Richmond to Bayonne Ferry. To his dismay, the ferry is guarded by Federal troops. He then tries to bribe a local boatmen for passage across the Kill Van Kull. The fearful boatman raises the alarm, "Deserter!"...

_______________________

in wooden camp at Staten Island (1861)About this Image:["From a sketch by our special artist." Written on border: "June 29, 1861." The Illustrated London News describes this image: On page 602 is depicted a characteristic group of "Wilson's Boys" encamped at Staten Island. "This corps," ['Special Artist' Frank Vizetelly?] writes, "might properly be styled the 'Chevalier Guard,' being composed principally of the chevaliers d'industrie of New York: they have no regular uniform yet, though I do not know but what their present costume is the most picturesque. The other day when their Colonel dismissed them from parade he took out his watch, and, looking at it, said suggestively to his men, 'This is the kind of watch they have in Baltimore boys.' This announcement was hailed by enthusiastic cheering." A second image of the camp is available from the ILN website.]

________________________

Mackay wrote little of his life at home on Staten Island other than a few passages in his autobiographies Forty Years' Recollections of Life, Literature, and Public Affairs (1877) and Through the Long Day: Or, Memorials of a Literary Life During Half a Century(1887). Through the Long Day contains some disparaging comments on his Irish servants and the payoffs he had to make to the Fenians to employ them:

"During my second visit and residence of four years in the country I travelled over less ground. My head-quarters were at New York, with a residence in Staten Island...I had two "Biddies" in my employ in Staten Island, one as cook and the other as housemaid,...Irish female servants, familiarly known as "Biddies," who receive high wages for rendering inefficient and saucy service in American households, which they do their best or worst to render uncomfortable by their ignorance... and also a negro lad named "Legree"; but poor Legree — who had been hunted down in New York during the Anti-Negro riots, and had taken refuge with a Southern gentleman, my next-door neighbour in Staten Island — was not permitted by the Biddies to take his meals in the kitchen, but was ruthlessly consigned to an out-house or a coal-shed, to eat alone, unworthy to associate with his superior Irish and white fellow-creatures. The " Biddy " rent or tax, so long levied by the head-centres and the tail-centres of the Fenian organization in America, has fallen off considerably..."

One can only guess how Mackay's servants felt about serving an English employer with such strong views on the Irish. He recounts another example of the ill will between the two nationalities. Sitting on the ferry listening to an Irishman recounting to other passengers, in a deliberately loud voice, how the British Press in America were stirring up animosity towards America and that should any such correspondent (like Mackay) "be found on the deck of a steamer he should be thrown overboard, or, if found on land should be strung up from the nearest lamp-posts."

Mackay also felt that race relations between blacks and whites were better in the South than the North because there was more interaction between the two groups, even if that relationship was one of master and slave. In Forty Years' Recollections he wrote of Staten Island during the New York City draft riots:

"My next door neighbour in a country villa in Staten Island, which I had hired for the summer, was a native of Virginia, a slave-owner, and of strong Southern sentiments, whom the outbreak of the civil war had found in New York with his family, and who had not been able to return to his native State and cast in his lot with his own people. The negroes, of whom there were many in Staten Island, betook themselves to the woods, where they encamped, resolved to do battle with their enemies; but one family, knowing my neighbour to be a Southern man and once an owner of slaves, boldly threw themselves on his protection, and implored him to give them shelter against the multitude. The request was cheerfully granted, and though his house was besieged by the crowd who threatened him with death if he would not give up the fugitives, he fed and defended them until the storm blew over."

William Winter described Mackay as "a compact, burly, ruddy-faced little man, and a commonplace, matter-of-fact speaker, sincere and sensible." Mackay counted among his American friends Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes. The "true love" of AT HOME is probably Mary Elizabeth Mills (?-1875), Mackay's second wife, who was probably also known as "Ellen" or "Nellie" and is only described as having "Italian coloring". Census records list her birthplace as Madrid so she may have been of Spanish descent. Ellen is believed to have been either a local washerwoman or the wife of a colleague named Mills. Mackay's first wife, Rosa Henrietta Vale left him in 1853, probably because of an affair with Ellen, and died in 1860. Mills and Mackay married on February 27, 1861. Though details are sketchy it is believed that Charles and Ellen had an "illegitimate" child, Mary "Minnie" Mackay, on May 1, 1855 more than a year after the separation of Rosa Henrietta and Charles.

There are no definitive answers to questions about Minnie's parents, though. Another theory places Minnie as the daughter of Rosa Henrietta, born after their separation, possibly in Italy, and adopted by Mackay and Mills upon Rosa Henrietta's death. The New York Times published a letter in 1910 that states Minnie was the daughter of an impoverished English mechanic named Cody who gave little Marie Cody to the Mackays because he couldn't support her. Another theory says she may have been Mackay's own granddaughter by his daughter from his first marriage, Rosa Jane, who died in Italy in 1855, and a London set designer named Corelli.

Charles Mackay wrote of his trip to the U.S. "I took my faithful and dearly-beloved wife and infant daughter along with me." Their daughter, Mary "Minnie" Mackay (1855-1924) must be the "infant" he mentions. His whole trip to the United States was probably motivated by the need to support his new family. Despite his earlier successes he was not wealthy. Note the line in AT HOME "Not rich enough to buy land...in Staten Island". He received a 100 pound pension from Parliament to help him support himself while on the Island in recognition of "his contributions to poetry and general literature." Minnie lived with her parents on Staten Island from early 1862 to late 1863, from about age 6 to 8 until Mackay brought Minnie and Ellen back to England. Mackay then returned by himself to Staten Island. Minnie would grow up to be the most-read author in England.

She incorporated what might now be called "New Age" ideas into melodramatic tales mixing romance, Christian theology, reincarnation, the occult and psychic phenomenon. Her novels include A Romance of Two Worlds, The Sorrows of Satan, The Mighty Atom, Soul of Lilith, The Secret Power and Vendetta. She published over 30 books, over half of them best-sellers. It's estimated she sold about 100,000 books annually in her prime, more than double what any competing author sold. Her most quoted line is: “I never married because there was no need. I have three pets at home which answer the same purpose as a husband. I have a dog which growls every morning, a parrot which swears all afternoon, and a cat that comes home late at night.” In one photograph her beloved dog is pictured chewing up a mouthful of her negative press clippings. She was as familiar to English readers as Charles Dickens at the height of her fame. By the end of her life her sales had dropped sharply. In 1906 G.K. Chesterton summed up the effect of Corelli's writing this way: "The man in the street has more memories of Dickens, whom he has not read, than of Marie Corelli, whom he has."

Marie Corelli publicly highlighted her mysterious Italian heritage. She once claimed to be "half American and half Italian" and the daughter of a Count Corelli, descended from seventeenth-century Venetian composer Arcangelo Corelli. She claimed to know her Italian godfather and uncle. At the age of thirteen she began writing an opera called “Ginerva da Siena” and incorporated lots of Italian phrases into her novels. A signed portrait of the Queen of Italy hung on her wall. She owned an authentic Venetian gondola, piloted by a gondolier in full Venetian costume who ferried her around the Avon river near her home in Stratford-upon-Avon, England.

There are a few clues about what she was like as a child. In 1866 she apparently was too difficult for her nanny and was sent to a convent school in Paris. She wrote of herself at age eleven: "I managed to develop into a curiously independent little personality, with ideas and opinions more suited to some clever young man. I distinctively did all I could to make myself a personality to be reckoned with. For this reason I devoured books whatever their qualities and fed my brains with the thoughts of dead men...I was indeed a very lonely child...I had to play by myself and invent my own sports and games" She also described herself as "pampered, petted and spoilt" She is said to have adored her father but wrote little about Ellen Mackay.

Marie Corelli always denied visiting the United States. Giving out verifiable facts about her childhood could have lead to the public discovery of her "illegitimate" birth. Yet, there is no other record of anyone else who could be the daughter Charles Mackay described. She reprimanded anyone who accidentally referred to Charles or Ellen Mackay as her parents. Upon the death of Charles she had a meeting with his lawyers where she learned something of his past. She wrote to a friend "if you ever wish to know the history of my relationship with the dear old man who has gone, I will sincerely tell it to you, though to do so, will possibly cast aspersion on the memory of him and my dear sweet Venetian mother; that is why I hold my peace...there are romances in every life, though not until ten days ago did I know there was such a romance in mine." The tangled stories about her personal life undoubtedly contributed to her strained relationship with the press. Because she never spoke publicly or wrote about her time on Staten Island there is no record of her experiences there.

AT HOME was not the only poetry Charles Mackay wrote on Staten Island. He produced a whole book of it. The Illustrated London News announced in November 1863:

"Charles Mackay, who for twenty months has been residing in the United States as Special Correspondent of the Times, returned by the last Cunard steamer on temporary leave of absence. That the Doctor should have remained so long unmolested and undenounced in the Northern States is rather complimentary to the impartiality and love of fair play of the Federals, whose peculiarities he has painted in vigorous but certainly not in rosy colours...Dr. Charles Mackay, who has been in England for some few weeks, is about to return to New York to resume his correspondence for the Times. As rumours from "good-natured friends" have been afloat concerning Times dissatisfaction with their correspondent's Southern tendencies, our readers will be glad to hear them so thoroughly disproved. Still more pleased will they be to hear that a new volume of poems by Dr. Mackay will be published immediately, under the artistic title of Studies from the Antique and Sketches from Nature" (1864). The first half of the collection contains poems about Greek mythology. The second half is dedicated to themes of nature. "Heart-Sore in Babylon" is dated "New York 1863". The second edition, from 1867, adds a preface that gives some background to the first edition.

There doesn't seem to be any mention of Mackay or AT HOME in the local historical records, so Staten Islanders may not have been aware of it when the poem first appeared. Despite what one may think of Charles Mackay's other endeavors, AT HOME still resonates, especially the concluding passages:

"Ah, well!" my true love said and smiled, " There's shade to every glory ;

There's no true paradise on earth

Except in song or story.

The place is fair, and while thou'rt here,

Thy land shall still be my land,

And all the Eden earth affords

Be ours in Staten Island."

There isn't a lot of poetry written about Staten Island. Islanders who have read the poem recently have commented on how meaningful it is to them. The forests and bird life are still there in greater quantities than most of the city. The mosquitoes are still an issue, despite development and pesticides. It is also still a place of people in transition as Mackay was. The borough is home to so many people who have their roots in other places or view the Island as a only temporary stop on the way to someplace different. The poem is a reminder to appreciate the place you are now. Ed Wiseman, Executive Director of Historic Richmond Town now has a copy of the poem on his office wall. Beth Gorrie of the "literary karaoke" Staten Island OutLOUD is planning a performance of it. It's good to see the small beginnings of a revival...at home in Staten Island.

****

More of Charles Mackay's poems can be found here .

Thanks to Patricia Salmon and Cara Dellatte at the Staten Island Museum for finding the reference to Charles Gilbert Hine. Thanks to Bruce Balistrieri and Robert Veronelli at the Paterson Museum for their help gathering information about the Fenian Ram. Thanks to Robert Armitage of NYPL, Leonard Marcus, Fred Kaplan, Mary Moran, Richard Curry and Patrick McCarthy, for help tracking down the authorship of AT HOME.

FOR FURTHER READING

Guide to the Marie Corelli collection of papers at The New York Public Library,1893-1955

Charles Dickens: The Life of The Author

Two excellent books, used in this post, are:

Teresa Ransom, The Mysterious Marie Corelli: Queen of the Victorian Bestsellers, 1999 (This includes a picture of Marie as a child before her stay on Staten Island.)

Richard K. Morris, John Holland, 1841–1914: Inventor of the Modern Submarine, 1966

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Dickens in Staten Island

Submitted by Enid Mastrianni (not verified) on October 1, 2017 - 7:17pm