The Librarian Is In Podcast

Book Club: 'Between the World and Me' by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Ep. 168

Welcome to The Librarian Is In, The New York Public Library's podcast about books, culture, and what to read next.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify | Listen on Google Play

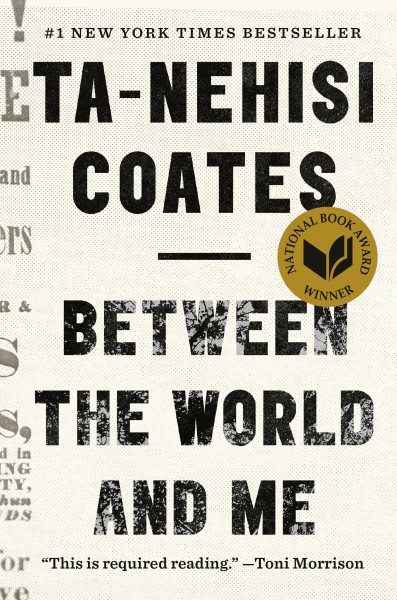

This week, we join Frank and Rhonda as they discuss the impactful and bestselling book Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates which appears on the Schomburg Center's Black Liberation Reading List. Did you read along? If so, don't forget to drop us a comment below with your thoughts.

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

More things we talked about today:

- The Other Wes Moore by Wes Moore

Tell us what everybody's talking about in your world of books and libraries! Suggest Hot Topix(TM)! Send an email or voice memo to podcasts[at]nypl.org.

---

How to listen to The Librarian Is In

Subscribing to The Librarian Is In on your mobile device is the easiest way to make sure you never miss an episode. Episodes will automatically download to your device, and be ready for listening every other Thursday morning

On your iPhone or iPad:

Open the purple “Podcasts” app that’s preloaded on your phone. If you’re reading this on your device, tap this link to go straight to the show and click “Subscribe.” You can also tap the magnifying glass in the app and search for “The New York Public Library Podcast.”

On your Android phone or tablet:

Open the orange “Play Music” app that’s preloaded on your device. If you’re reading this on your device, click this link to go straight to the show and click “Subscribe.” You can also tap the magnifying glass icon and search for “The New York Public Library Podcast.”

Or if you have another preferred podcast player, you can find “The New York Public Library Podcast” there. (Here’s the RSS feed.)

From a desktop or laptop:

Click the “play” button above to start the show. Make sure to keep that window open on your browser if you’re doing other things, or else the audio will stop. You can always find the latest episode at nypl.org/podcast.

Transcript

[Music]

[Frank] Hello. And welcome to The Librarian is In, the New York Public Library's podcast about books, culture, and what to read next. I'm Frank.

[Rhonda] And I'm Rhonda.

[Frank] And we're both here.

[Rhonda] Yes, we are.

[Frank] Persisting.

[Rhonda] Yes, together and apart at the same time.

[Frank] Yeah, I mean, I really miss that. Well, you know what? I miss it. But I think it's essential. This is one-on-one facing another person and having a conversation. I ran into a patron from the library the other day like wandering around my neighborhood because I live in the same neighborhood as the library. And, you know, I didn't expect it. But as I started talking to them wearing masks six feet apart, I suddenly went into like hyperdrive of babble. Like I couldn't stop talking. And I think I just suddenly clicked into missing talking to people. And I just found myself talking like a crazy person. so I was really happy about it. But it was interesting. So like talking about books with you is so different when you talk face to face than when you do it like this, which is remotely.

[Rhonda] Yeah. I feel like it's going to be, you know, New York is starting to slowly reopen now. So I wonder, you know, like you didn't really expect that you're going to, you know, have all of these things to say when you saw this person, what it's going to be like when we actually start kind of getting to see each other and talking to each other again, you know. I took my cat to the vet this past week. And it was so interesting because, you know, they took my cat. And then I had to stand outside and talk to the vet on the phone.

[Frank] Oh, really?

[Rhonda] So yeah, so I couldn't go inside. And we did the whole kind of thing on the phone while she had the cat. And it's just kind of the way the world has changed and how we've kind of gotten used to it and what it's going to be like when we're able to really see each other and have conversations with each other, you know, face to face again. It'll be nice.

[Frank] Yeah. And I've also just, I don't know, come to dislike very much the phrase the new normal. I sort of don't like it. And I don't know why. I think in a way because I resist the idea that there ever was a normal, you know.

[Rhonda] Yeah, that's interesting.

[Frank] Like this concept of normalcy. But I almost see it as like, you know, the world has always been a crazy changeable place. It's almost like I'd like -- I don't know. I'd almost prefer to think of it as just, you know, it's life, that we're going through life and we have challenges. And we remember what the primary focus is and that's other people. I don't know.

[Rhonda] Yeah. And, like you said, it's kind of humans are adaptable. And this kind of change is just inevitable. I saw a play, an entire play done on Zoom this weekend. And I was just like so impressed, you know, about how easily people are kind of able to just like adapt to these new technologies and to these new ways of like delivering art and information and even the way that we're doing the podcast now. So, you know, we're just kind of adapting. It's --

[Frank] Can I ask the play?

[Rhonda] So the play was called Cuttin' Up [assumed spelling]. And it was, you know, it took place in a barbershop. So in the Zoom, you know, they had the different actors who had the barbershop scene behind them. And, you know, they were able to edit and add musical cues. And, you know, they had costume changes. And it was part of the Classical Theater of Harlem. And I was just so impressed that I was actually seeing this like full production that people were doing, you know, from these different, you know -- no one was in the same room. And I was just so impressed. And I'm like, wow, people have really figured this out, you know, in such a short amount of time. I mean, 13, 14 weeks, it feels like a long time. But, you know, in the scheme of things, you know, it's not that long. And people really have like been able to just kind of like pick up on new ways to communicate, to connect, and to deliver different, you know, messages and art forms. And I don't know. And again, like you said, the new normal, I wonder if, you know, even when we go back to being able to be with each other and talk to each other, are these kind of things going to continue? I'm interested to see.

[Frank] Yeah. Well, I mean, you know, disliking the new normal is one thing. But also I know that, you know, nothing, nothing ever stays quite the same for too long anyway. So things do change always. They just might not seem to change for a long time. But things are always changing, even if it's imperceptible. But it's interesting. The only thing I've partaken in, in terms of online stuff is watching theatrical productions, too. A group called the Theater of War does classical texts and actually relates them to social issues of today. Like Oedipus, I watched. And I thought it was great. I don't know. For some reason I've been attracted to watching -- I guess watching people's creativity, like you sort of just said, manifest and negotiate a different way of conveying it. So I've enjoyed that. But what we were saying before -- actually, it keeps running through my head, this whole new normal thing and not liking it seems to somehow lead into the book that we both talked about.

[Rhonda] Exactly.

[Frank] Do you think so? Which Rhonda and I, we read Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me.

[Rhonda] Yes.

[Frank] And it's one of the books on the Schomburg's Black Liberation Book List.

[Rhonda] Yes, it is. Yeah.

[Frank] Am I correct in that designation?

[Rhonda] That is correct. Yeah. It's one of the 95 books on that list. And, you know, I don't know if you want to jump into it.

[Frank] [inaudible].

[Rhonda] You know, I kind of think like with the new normal, this was written, you know, the book isn't that old, you know. It's a few years old. But it does seem like, you know, he was looking out of his window today and writing a lot of what he was seeing.

[Frank] Well, that was really startling.

[Rhonda] It was -- yeah.

[Frank] It's from 2015. And it was a huge success in terms of readership. And it's nonfiction. I mean, I guess it can be cataloged as, you know, lots of different things. But it's nonfiction. And Ta-Nehisi Coates writes it in the format of a letter or a message to his own teenage son about the condition of Black people in America and the history of that. I haven't read it. But I realized it was modeled on, at least the format, by James Baldwin's The Fire Next Time.

[Rhonda] Yes, exactly. Yeah.

[Frank] But the new normal thing is sort of like that Make America Great thing in that, you know, who's normal are we talking about here?

[Rhonda] Right. Yeah, and he kind of refers to the group, you know, of, you know, White America, I guess, as the Dreamers, you know. Those are the ones who have the dream and who are actually able to kind of adhere to this idea of the American Dream, which was kind of built, as he talks a lot about, which I believe is like the very first part of the book, on Black bodies. And he begins, you know, the book with what the question that he had to ask himself is what is it like to lose your body. And, you know, reading that again is kind of like what really ties into what's happening, you know, in the U.S., in the world right now.

[Frank] Oh, I mean, the issues he was talking about, the book could have been written yesterday.

[Rhonda] Exactly. Exactly.

[Frank] And in terms of that though like I think that there was a -- it's not hopelessness, a sort of clear-eyed fatalism of sort about the status of the struggle of Black people. And I think what's happening now, Ta-Nehisi Coates would actually -- I think I've even read that he's sort of like this is a very new development in terms of the revolutions of social groups in this country. And that it's something new and actually hopeful because what is not discussed in the book but is happening now, the rebellion or protests are multiple groups of people, are pan-racial in a way, that White people have gotten on board where Ta-Nehisi Coates talks about his parents' generation in the '60s, it was Black communities protesting and fighting. And now it seems it is far more widespread. So that's a change. But --

[Rhonda] And I saw kind of that idea of the fatalism as, you know, there's a line that he writes about his son saying, you know, "You don't really have the privilege to live in ignorance." And, you know, a lot of what I saw in that, you know, I guess as you describe it hopelessness is kind of, you know, teaching his son that, you know, this is the world that you are going to have to grow up in and live in. And I don't feel good about trying to kind of sugar coat this or making you kind of believe that it is possible in your lifetime that these kind of systemic changes that we've had for hundreds of years are really going to change, you know, one person's ideas or just a couple persons' ideas. And it's interesting because I haven't read what Ta-Nehisi Coates has kind of written about what's happening right now. But I do believe he was kind of, you know, really trying to impart to his son that, you know, as hard as it is, you know, as hard as it is, you know, when he saw his son crying over Mike Brown, you know, this is what the reality is. And this is kind of like what you are going to have to live in for the rest of your life, you know.

[Frank] You know, that's a good point because it's also -- like I didn't want to use the word hopelessness or despair or because, I mean, I personally also do believe I would rather know a hard truth about myself or about the world in which I live than be ignorant of it. To me, that's a value that maybe that I like. And I don't find it despairing because what, I mean, Ta-Nehisi Coates basically says to his son is that there isn't a lot of hope. And hope is not even the question. It's not about hope. It's not about solutions. It's not about results. It's about being conscious and the struggle. He wants to nurture him into a conscious state, which is probably, I think, the most wonderful state to be in. And I don't think a lot of people might agree with that. Or I'm not saying I'm so special but like you know what I mean? Because he does contrast that with, which is a difficult thing to read about the Dreamers. Basically he doesn't call them White people all the time. He calls them the Dreamers in the Dream basically a delusion, like a mass delusion of Whiteness and privilege. And, I mean, like I said before, that horrible Make American Great thing. It's like when was it ever great and for whom? That's the biggest question. It's like when you're saying Make America Great. When, what, in the '60s? Like who was that great for? So it's like White people basically, you know. They could sail through their lives without a lot of kerfuffle about their own identities because those identities were so concretized in what we have come to call the American Dream. And it [inaudible] a lot of it.

[Rhonda] Yeah. Right. And I think, you know, one of the ways that he really displays that so well is when he does talk about the police encounters and the police killings because he kind of makes this point, you know, that to him it really isn't about a single officer who is kind of killing a single person but that the single officer -- and I think this is a quote. I wrote it down -- is, you know, there was a friend of his that was murdered by the police. And he goes, "He was killed by this officer as much as he was murdered by his country and all of its fears that were marked from its birth," and kind of showing like, well, this incident, you know, it just didn't happen. This isn't new. This is a continuous line of, I think as he says, a tradition of kind of destroying and taking over the Black body. So just kind of seeing how everything is really kind of connected from the beginning of the United States until now. And I think that kind of goes into what you're saying about, you know, kind of, you know, people being able to live, you know, maybe not so much in ignorance but without thinking of the whole history behind what we're seeing now, you know, everything that's led up to why the police are able to get away with certain things and why that's connected to people bringing down statues. And in order to kind of understand that, you really have to see the whole history and not kind of just the White version. And he gets really deep into that because he goes into, you know, being a child in school and really beginning to see systemic racism without kind of understanding what that's about and kind of his journey through like self-education. So I don't know where I'm going with this. I'm kind of going off the rails. But, you know, the kind of idea of trying to see everything that's led up to these moments and how not everybody does see that.

[Frank] Right. Right. And it was a journey as a reader to understand and feel his use of the word bodies like when he very clearly and adamantly states Black bodies. And I was like bodies? It was almost like disconcerting because it kept reminding me of bodies like just human bodies in space. And then as I read it, I realized it's the best term possible because it is literally that. It is literally what life is really about is literally our biological bodies, our bodies that move through space and feel pain and feel all the emotions that humans have and how those are vulnerable, extraordinarily vulnerable in lots of ways. And to keep rooting it in that eventually became clear to me because, I mean, what do you think Ta-Nehisi Coates delineates as sort of the origins of this dream of America and the Black bodies in it. And basically the need, a human need, manifested very clearly in American history of an exceptionalism take on culture that White America could not exist without Black America, meaning that Black had to be below, had to be beneath, had to be subservient to White American in order for White America to have its dream.

[Rhonda] Mm-hmm. Yeah. Yeah, and so in a lot of that, when you were saying, you know, where you were thinking about the bodies as kind of like physical bodies in space, I think in a way that really is what he was talking about, kind of the physical bodies because there is a part of the book where he does kind of go into the history of black bodies as really America viewing them just as that without kind of the humanity connected to it, you know, because how else can you really have slavery without disconnecting the actual humanity of the person from the body, the body as the commodity, the body as the, you know, the property, the tools, going through slavery, through Jim Crow, and even, you know, being able to mercilessly kill someone, you know, in the streets with no justice. In a way, you have to disconnect the actual person, the humanity from those bodies and able to kind of do those things. And I think that's why he talked about the fear that he's always kind of experiencing for himself and for his son is that he knows that a lot of the country and the tradition is to kind of see Black bodies as property, as tools, as commodity, and that kind of stems from how this country was built on the bodies and the labor of slaves, which were not seen as human beings, you know. And that's kind of how I saw that.

[Frank] Yeah. I mean, it's a difficult pill for someone like me to take in, in terms of, you know, there's that very White feeling of like, well, you know, we all have opportunity. And things have changed. And it was just certainly true and Civil Rights and all of that. But to sort of really realize how that dream of America is so embedded and ingrained in a White person's psyche, which isn't true either, like that you can be whatever you want. You can do whatever you want. I mean, ultimately, you have to choose. And ultimately you can't be anything really that you want. But that dream embedded in the psyche of powerfulness, regardless of any kind of abuse or discrimination I personally have felt in my life, my Whiteness sort of overruled it or could overrule it or could be something I could slip through or get through because of that, because of Whiteness. And it's such a tough concept to take in. You know what I mean? Like to really hear him because you really want to resist. Like I'm not in that. Not me. And then you realize you're a part of it in a way. You are. I am. And it was an interesting journey to read. Sometimes I had to stop reading when I was just like I can't take it. And also to know that the book -- he isn't also talking to me in some ways. He's talking to his son, his people. And there is that sense I had reading it that I'm outside. Like and I'm like, "Wait, I want to come in. Like let me in." And it wasn't about me. [laughs]

[Rhonda] Yeah, yeah. And again, yeah, he is talking to his son and again just trying to bring truth to his son kind of about all of his experiences. And what you were saying about, you know, you know, people being able to achieve these American Dreams and how that kind of really can mostly apply to White people, he really goes into that, I believe, when he talks about his really -- or not really good friend but a friend of his, Prince Jones, who was murdered by the police, and how he kind of did everything that falls into the American Dream. Like his mother was a very well-known doctor. And he went to college. And he went to the best private schools. And he played instruments. And he, you know, was involved in the community. But when it came down to it, really all the officer saw was, you know, this dangerous, you know, Black body. So the American Dream kind of didn't apply to him because what was seen, what he was kind of exhibiting to the officer at that time was the years and years of what was kind of placed -- the burden of all Black bodies placed on this one Black body, you know. So that, yeah, even though he did have that Dream and he achieved that Dream. At that moment, it didn't matter.

[Frank] Which is an awful thing to read. I mean, the officer in that situation was Black as well.

[Rhonda] Mm-hmm. Yeah.

[Frank] And it's like when you read that, you know, the White side could say, "He must have done something, Prince Jones, the young Black man who got killed in that situation. He must have done something. He must have reached into his pocket." And then if you keep pushing that, you think, well, reaching into one's pocket is not a crime. I mean, you know what I mean? Like when you really start thinking about it, it opens up a chasm of, oh, God, no, it can't be. It just can't be. Because that Dream includes saying there is fairness, that you have to be bad if you're going to get killed like that. You have to be somewhat bad. It can't be the just racial. And yet it is.

[Rhonda] Right. And I think that was part of why he talks about Howard and his experience at what he calls the mecca, Howard University, the Historic Black University. His self-education was so important to him because, you know, kind of isolating that one incident and thinking, well, maybe he must have done something. But then through all of the things that he read, through reading the Malcom X and all of the other things, seeing that history of this happening to so many Black men in different ways, you know, from all of these different police encounters to Trayvon Martin to Emmett Till to the lynchings and the things that happened, you know, right after slavery and the fact that this has been repeated over and over and over, you know, his self-awareness in that makes it seem like, okay, yeah, you can no longer say that he must have done something because the tradition here is just way too long. And this is something that's systemic. This is something that's kind of ingrained in the American psyche of equating the Black body with this idea of either, you know, being dangerous or having this lack of humanity or any other myriad of the country's fears that have been put on Black people. So kind of his self-education, his times reading in the library experiencing that, you know, has shown him like, okay, so this is what it is. They're always going to say, you know, maybe he did something. But there's all of this history behind it to show kind of what the situation really is.

[Frank] And that concept that I referred to before, that can a group of people, just as humans, kind of a group of people exist in an exceptional way or considered self-exceptional without the denigration of another group of people. Like he basically says that, you know, throughout history, cultures who have become imperial and successful have always had to have a below-stairs class or group of people, a whole culture that is considered not them to put what their exceptionalism is into relief, into positive relief. And that's a tough thing to read about humanity and realize, like Ta-Nehisi Coates does as he talks to his son in this book, that forget about those solutions. It's about the daily struggle. He has lots of great quotes where he says like -- he says this in multiple ways throughout the book. Like let's see. He's talking to his son. "I have always wanted you to attack every day of your brief, bright life in struggle. The people who must believe they are White can never be your measuring stick. I would not have you descend into your own Dream. I would have you be a conscious citizen of this terrible and beautiful world," which says it like how the world is both terrible and beautiful. And he certainly doesn't deny or want to deny his son's own joy in life.

[Rhonda] Yeah. And I think he --

[Frank] And he wants him to [inaudible].

[Rhonda] Sorry. Oh, yeah. And I think he really does struggle with that in terms of, you know, he's telling his son he's always going to have to live by a different set of rules. But kind of what you were saying about how this kind of applies to every nation in the world, you know. He takes his son to Paris. And even though he talks about how France has kind of done all of these horrible things to the Haitian community and other places, he still was able to live in that space without fear, you know. And so that no matter his son having to live by different rules in the world, there are still places and are still moments where he can live without fear, where he can still, you know, have joy, you know, again going back to his community and what he called his mecca and going to Paris, you know. So I feel like he struggles a lot with trying to have that balance with his son of making sure that he understands what he has to do to survive and to kind of protect himself but that he shouldn't have to constantly live in fear without any form of joy.

[Frank] What is it about French culture or Paris particularly? Like James Baldwin went there as well.

[Rhonda] Yeah, and other writers, too.

[Frank] Yeah, as that culture as being much more what? Accepting or integratively accepting? I don't know. Do you?

[Rhonda] I mean, that's kind of what I would assume, you know. I haven't really like, you know, studied the history of this. But at the time when Baldwin was going over and I can't really remember what other authors, maybe Richard Wright that he was talking about, you know, that was, what, the '50s, pre-Civil Rights movement. And Black people kind of just were not treated the same over there as they were over here, I'm assuming. I mean, I'm assuming there were still some forms of racism. But they could probably exist, as Ta-Nehisi says, without fear, you know.

[Frank] Yeah.

[Rhonda] They could go into a place without the fear of violence on their bodies, as Ta-Nehisi, you know, speaks about or of the fear of the humiliation. So I'm assuming that that's kind of what that space provided for them. They could have a moment without fear. Yeah.

[Frank] Yeah. It's like that thing that he also talks about in the book about there's this insistence upon American innocence. Like that contrast that has always been made about Europe and America, that Europe is older and wiser and has a bit more wisdom and a little bit more of a laissez-faire attitude towards people. And American is much younger and much more like almost like a teenager, caught up in how they look and what they want to be perceived as. And so Ta-Nehisi Coates talks about this in the book about this insistence on American innocence and superiority, that we're a very innocent, open-faced, striving, powerful country. And he takes issue with that concept of innocence, which Europe doesn't seem to take, doesn't seem to consider itself. This insistence on innocence and purity and greatness covers up an enormous amount of so-called sin. And Europe has been through it, baby, and doesn't insist on that. I think that's a tension that, if you're on the Black side of the equation, must be a daily pain in terms of hearing that American is so wonderful. America is so innocent. America is such a place where anybody can be whatever they want to be.

[Rhonda] Yeah. And, yeah, I believe one of the terms he says that America thinks that they're, you know, exceptional and that they're this great, you know, democratic, you know, country where everyone has a say in the government and everyone has a say and the way that we can move through the society and the policies. And, you know, we're seeing again today that that's really not the case, you know, in terms of like the different voter suppression tactics that are still happening in our current environment. And that America's belief that they have this great democracy and that everyone has a say and everyone can, you know, move forward. But the evidence, you know, shows that that's false. And I guess, like you said, because we're a younger country, we believe that we were able to kind of build the society in the way that certain people envisioned it, that that might make us better in terms of the history of other countries. Yeah.

[Frank] Yeah, I mean, I feel like, tell me if you agree, I mean, what do you think of his, you know, final sort of if there is a solution, which there isn't, just exhortation to his son that let me let Coates tell you.

[Rhonda] Okay.

[Frank] Because I wrote so many notes down. And now I'm getting verklempt about reading my notes because they're incoherent. I don't know.

[Rhonda] There was a lot packed in that little book.

[Frank] Oh, boy. It's 150 pages. But it's not like, oh, I'll read it in the afternoon. I couldn't read this all at one stretch personally.

[Rhonda] Yeah. It's a lot to sit and reflect on.

[Frank] Oh, for sure. That's why I feel like I want to pick up more of my quotes or the quotes that I made notes of because there was so much well-put. I mean, I keep going back to that, which I think is such a wonderful thing for a parent to want for a child, is to be fully conscious about the world in which you live. It's like I said that at the beginning. That's such a value to me. And I don't particularly know why. It seems so obvious. But I don't think that's necessarily a value for everyone.

[Rhonda] Yeah because I think -- sorry, go ahead.

[Frank] I say that with a -- well, go ahead. Please.

[Rhonda] No, I was just kind of saying like, you know, it is a great thing. But I also think that he's kind of saying you really don't have a choice not to know this because I'm afraid if I don't tell you this, then you will be in a situation where you won't have the knowledge to kind of defend yourself, to protect yourself. So kind of as I said before, he doesn't really have the privilege not to know this information because he doesn't know when he'll be presented, you know. Maybe he's with the police or some other situation where this knowledge could possibly save him, you know.

[Frank] Yeah. Yes, yes. You're right. Do you have any other passages you marked?

[Rhonda] So, I mean, like you said, he had so many different things that were packed into this small, small book. And one of the things, you know, working at the Schomburg Center that again has kind of stood out to me is kind of his progression of, you know, self-awareness and kind of knowledge of his place in the world because he begins talking about, you know, there were the laws of the street that he lived in. and then he had to kind of learn the laws of the school. But then when he began, you know, going to the library and picking up, you know, his own, his self-education, reading books that were never kind of presented to him before was when he really began kind of this odyssey, this journey of what it was like, you know, to really experience his Blackness in America and kind of be responsible for his own place in the world. And I don't know. I thought that really stood out to me because at the Schomburg Center, we kind of see that every day, you know, kind of people coming in really trying to understand the experience and the place that they're living in that they didn't get in school or they didn't get growing up in the streets or they didn't get in other places and kind of how that experience really brought him to where he is today, you know, being able to talk to his son and being able to help his son understand where he is more than he was able to at that age. So that was something that, you know, I guess as a librarian, you know, really stood out to me.

[Frank] That's interesting, yes, because he does say -- I found a quote I had marked that he says, "I came to see the streets and the schools as arms of the same beast. One enjoyed the official power of the state, while the other enjoyed its implicit sanction. But fear and violence were the weaponry of both. Fail in the streets and the crews would catch you slipping and take your body. Fail in the schools and you would be suspended and sent back to those same streets, where they could take your body. And I began to see these two arms in relation, those who failed in the schools justified their destruction in the streets. The society could say, 'He should have stayed in school,' and then wash its hands of him." And then he goes into this part. "It does not matter what the intentions of individual educators were noble. Forget about intentions," he says. "What any institution or its agents intend for you," he's saying to his son, "is secondary. Our world is physical. Learn to play defense. Ignore the head and keep your eyes on the body. Very few Americans will directly proclaim that they are in favor of Black people being left to the streets. But a very large number of Americans will do all they can to preserve the Dream. No one directly proclaimed that schools were designed to sanctify failure and destruction. But a great number of educators spoke of personal responsibility in a country authored and sustained by criminal irresponsibility." That was a strong part about, and I said it before, where people would say, White people would say, you know, "Well, you have to have personal responsibility over your own life and be peaceful and pursue it that way." And then the world that Black people understand, according to Coates, is that personal responsibility is just like code for like you deal with the basic violence and violent past of this country because we're not going to make it better for you. We're not going to do it. We aren't.

[Rhonda] Yeah. And I agree. Yeah. And, you know, some Black people will say the same thing about responsibility, too, you know, you know. There are Black people who do believe that. And I don't know. There was another book that came out maybe around the same time as this book called The Other Wes Moore. I don't know if you've heard of that book. But, you know, it was about two Black men in Baltimore just like Ta-Nehisi Coates. They had the exact same name. and on the exact same day in the newspaper, one of the Wes Moores was sent to prison for life for robbery. And the other Wes Moore, I mean, sorry, had a Rhodes Scholarship. And kind of the purpose of that book is to explore what is the balance between personal responsibility and, you know, dealing with the system, dealing with the way that the country is treating Black men. So that's a really interesting point because that's a debate, you know, not just between White people. But Black people also, you know, have that thought as well, you know. How much can we actually control? How much can we actually pull ourselves out of systemic racism? And, you know, there's arguments on both sides. But you see again the very end of the book when he's interviewing his friend Prince Jones' mother, who says, you know, "I tried to do everything. I tried to take as much responsibility. I tried to put him in the best schools, you know. I became the head doctor in my hospital. And still, you know, this is what happened." So that's a heavy conversation to have.

[Frank] Well, that's why, you know, people have said that this book can be very desolate. And that story especially is hard to read. And it comes up multiple times in the book, where he actually writes really eloquently about the many seemingly small things we do in our lives to further our lives or the lives of our children or the lives of our family like, you know, driving to school, working two jobs to give them some benefit. And then it ends in a minute from some violent act. And it does sound despairing. But when you really, really live in that concept, the daily struggle and the daily moments of our live are all we do have. And that is worth it. It is worth it. I mean, the mother of Prince Jones would have a hard time agreeing with that. And like how can we disagree with her? But when you can step outside of it, which is hard because we're all living our lives, it is the only way to be. But I forgot what I was going to say. But yeah. You were talking before so about the other book.

[Rhonda] Oh, yeah, The Other Wes Moore, just to illustrate your point, you know, that that's a common [inaudible] --

[Frank] Oh, that personal responsibility we were talking about.

[Rhonda] Right.

[Frank] Right. Mm-hmm. That definitely was made very clear in this book, that the concept of personal responsibility, sure, like it's all we ultimately have, absolutely. But he's saying I think as a society, you can't say, "Oh, you've got to be personally responsible," when the 400-year history, practically more than not has been, as he says, criminally irresponsible to a huge group of people. Right? You know, so it's like you cannot suddenly say that and be believed, you know, be personally responsible when there has been such irresponsibility. That concept of America as being we're innocent. We're good. Like you can do whatever you want in life. You could pursue. You've got the same opportunities, even more so, you know. But it's not the case. Ugh.

[Rhonda] I know. [laughs] There's so much.

[Frank] I know. Yeah, it's amazing times we're living in. And it is such an interesting time to read this book because of what's happening right now. There is change.

[Rhonda] Right. And I --

[Frank] Oh, go ahead.

[Rhonda] No, I was just going to say I'm interested -- it would be a good exercise to maybe read this book again maybe, I don't know, a year from now, five years from now and see, you know, if this moment is a transformative moment in the United States.

[Frank] I know because like I sometimes think of activities from the '60s who have lived obviously for the last 50 years or almost what they would have thought about how slow change happened, you know, the incredible upheaval of that time that didn't necessarily result in radical change but did result in some change. It would be interesting. But I have to say I did read an interview that Ta-Nehisi Coates gave recently about -- I really wanted to know what he thought about Black Lives Matter and the movements that's happening right now. And just in a nutshell, he did say, which I love how he said it, considering this book, when the interviewer asked him, he said, "Believe it or not, I am hopeful." And I love how he said believe it or not because his book has been accused of being unhopeful. And he understands that. So he's playing with that but also that he is hopeful. And I took it from him. He said because of the wide range of people involved in these protests that are not just Black people saying, "We need change," it's other people. And that's what a lot of people have said needs to happen.

[Rhonda] Exactly. And, yeah, I can see how people have kind of thought of this book, you know, as almost hopeless. But I did see some hope in it when he took his son to Paris because he was trying to open his son up to all of these different experiences and to make sure that his son knew that there were ways to kind of go out there and experience joy and, you know, talked about the homecoming at Howard and how to experience, you know, the joy within his people. So I thought kind of having those experiences at the end of the book and trying to expose his son to those things, I thought that that showed some hope.

[Frank] Mm-hmm.

[Rhonda] Yeah.

[Frank] I agree.

[Rhonda] That's what I think in those moments.

[Frank] I thought it was a tough book to read. But I didn't find it despairing at all. We should all be so lucky to have a father like him, you know. [laughs]

[Rhonda] Exactly.

[Frank] Anyway. All right. Any final thoughts?

[Rhonda] Well, I think that was a great discussion.

[Frank] Well, do you?

[Rhonda] Yeah.

[Frank] Well, thanks, Rhonda.

[Rhonda] I always think we have [inaudible] discussions.

[Frank] Thanks for the compliment because it is all about me. So I guess next time we'll be reading what we want to read.

[Rhonda] It's our choice. Yeah.

[Frank] Not that we didn't want to read this. But it's a free for all. I'm looking forward to that.

[Rhonda] I am, too. I've been looking forward to see what you pick up, Frank. [laughs]

[Frank] [laughs] What I pick up.

[Rhonda] What you pick up.

[Frank] Hey, beautiful. Come on out with me, baby. [laughs] Oh, dear. So as the summer goes on and we navigate our lives and see how we get back to work, take care of yourself, Rhonda.

[Rhonda] Yes, and you, too, and everyone out there.

[Frank] Absolutely.

[Rhonda] You know, it's a unique time. No one has ever experienced all of this at once, you know.

[Frank] It is.

[Rhonda] So everyone has to really just be gentle with themselves. It's a lot.

[Frank] It's not easily living through history.

[Rhonda] Exactly. Exactly.

[Frank] Yeah. All right. Well, it's a pleasure as always. And thanks, everybody, for listening. And we will see you soon.

[Rhonda] See you soon.

[Narrator] Thanks for listening to The Librarian Is In, a podcast by the New York Public Library. Don't forget to subscribe and leave a review on Apple Podcast or Google Play or send us an email at podcasts@nypl.org. For more information about the New York Public Library and our 125th anniversary, please visit NYPL.org/125. We are produced by Christine Farrell. Your hosts are Frank Collerius and Rhonda Evans.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

I loved this episode! I

Submitted by Brianna (not verified) on July 2, 2020 - 7:50pm

I read this book last year (I

Submitted by Patricia (not verified) on July 6, 2020 - 8:18am

It doesnt matter which podcast we listen

Submitted by Christina (not verified) on July 7, 2020 - 7:59pm

Between the World and Me

Submitted by H. Patricia Bla... (not verified) on July 13, 2020 - 4:53pm