Africa and the African Diaspora

The Howard Colored Orphan Asylum: New York’s First Black-Run Orphanage

Black New York: In 1625, eleven enslaved Africans arrived in New Amsterdam to physically clear the land for what we now know as New York City. Some parts of New York, such as Harlem, are well-known Black neighborhoods, but Black people have lived in and impacted all parts of New York City for centuries. Let us take some time to explore the many areas of New York City where African Americans have lived and thrived. For this segment we are heading to Brooklyn, circa 1870…

A Place For Freed Children

In 1866, just three years after the Emancipation Proclamation, freed Black women were travelling North with their children, many finding their way to New York City. Upon arriving they were hit with the reality that the families who would hire them for domestic work, often the only work available to them, would not allow them to keep their children. This provided a painful dilemma for these newly freed African American women who had come North seeking an improved life. They had no choice but to work, often caring for the children of White families, but who would care for their children? Orphanages were one of the few available options at the time. However, orphanages, whether government or privately funded, refused to accept Black children. Black orphans often ended up in different forms of servitude—not far removed from slavery, living on the streets, or sometimes even housed in jails. However, one African American woman, recently widowed, decided to take matters into her own hands, and by 1866 Sarah Tillman was taking care of twenty Black children in her lower Manhattan home.

Henry M. Wilson, an African American Presbyterian Minister, worked with Mrs. Tillman to find a solution by starting, what was then termed, an orphan asylum. The number of children in need was growing and the one orphanage that did accept Black children—the New York Colored Orphan Asylum founded by the Quaker community—had been burned to the ground during the New York draft riot of 1861 and had yet to be rebuilt. Utilizing his role as a minister, Wilson organized a group of women from various Black churches in Brooklyn to start the Home For Freed Children and Others, located near the Black Brooklyn neighborhood of Weeksville. Wilson was also able to gain financial backing from Oliver O. Howard, a General in the Union Army (also the namesake of Howard University) and in 1868 the name of the orphanage was changed to the Brooklyn Howard Colored Orphan Asylum.

Despite the backing of General Howard, Wilson held very strong feelings about who should run the orphanage, desiring to keep the staff entirely Black. Wilson was a member of the African Civilization Society, who advocated for segregated schools and other organizations, believing that self-reliance was the best path for African Americans moving forward after the Civil War. Wilson managed to bring in Black teachers and caretakers for the children, including having an entirely Black board for the first few years, with Mrs. Tillman as the head. This put the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in a unique position—as one of the few orphanages for Black children run entirely by African Americans, with the support of Black churches and strong ties to the Weeksville community.

Underfunded and Overcrowded

Only a few years after settling in Brooklyn, the Howard Colored Asylum was in near financial ruins. Mrs.Tillman, after leaving New York City, was no longer head of the board, and Wilson was blamed for the mismanagement of the Asylum’s funds. A Grand Jury investigation was held by the comptroller at the urging of funders. During the investigation the Comptroller stated that, not only had the funds been managed poorly, but there was also extreme overcrowding. The managers of the Asylum at the time (all Black women) took action by removing Wilson and replacing him with William F. Johnson, who began to steer the orphanage in a better direction.

There was another issue that the Howard Orphanage was facing. It was very common for orphanages to participate in the “indentured system.” The children would be hired out and the money made was to be held at the bank for them and turned over on their twenty-first birthday. This system was heavily criticized, especially concerning Black children, because it was too reminsciant of slavery. Other institutions, such as the New York Colored Orphan Asylum, instead of indentured servitude, began to place children in foster homes. However, Johnson chose not to go that route, instead choosing education, using the famed Tuskegee Institute as his model.

The Tuskegee Plan

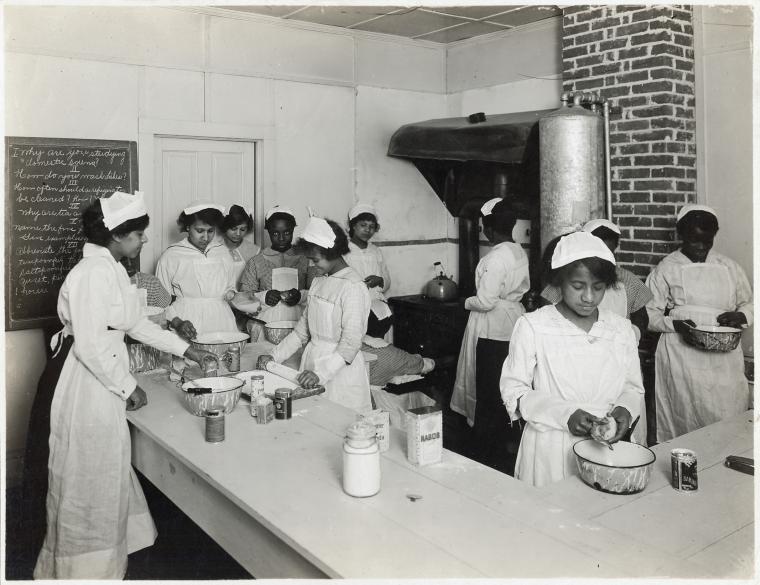

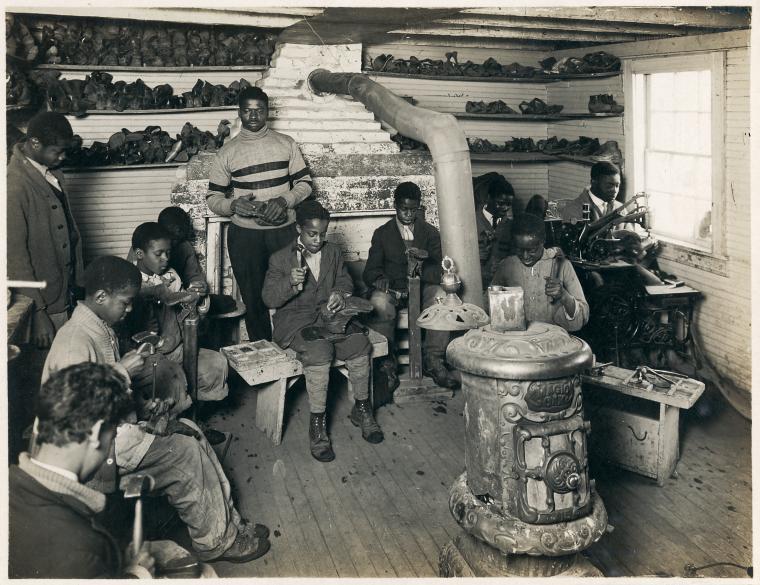

An annex was added onto the school in 1894, and as described by Carleton Mabee in the 1974 article, Charity in Travail: Two Orphan Asylums for Blacks, the industrial school was “not so much education for factory work, as the term might suggest today, as education in housework, manual arts, and agriculture. The asylums had long given some such education, as in the form of sewing classes, household chores, and indentures to craftsmen and farmers.” However, another setback soon appeared. “In 1910...the State Board of Charities declared that the Howard buildings in Brooklyn were unsafe and overcrowded, and forbade the asylum to accept more children from public agencies.” The board chose to leave Brooklyn and move the orphanage and industrial school to Long Island. At first, the school and orphanage seemed to set a new course. Teachers were brought in to help the children and young adults learn all types of trades, such as shoe repair and cooking. However, money issues came up again, and Howard could no longer maintain the industrial school. As the United States headed towards the first World War, things at Howard were becoming dire.

Ota Benga

An interesting detail that remains part of the history of the Howard Colored Orphanage and Industrial School is the story of Ota Benga. Ota Benga, a young man from the Congo—a member of the Mbuti or pygmy—was sold by a slave trader to an American businessman. Benga was put on display at places like the Louisiana Purchase Exposition and in the Monkey House of the Bronx Zoo. The Black community was appalled at the treatment of Benga and petitioned the mayor of New York for his release from the zoo. Benga was eventually released, and not knowing where he should go, for a short period of time he had his own room in the Howard Colored Orphanage and Industrial School.

The War and Closing of the Orphanage

The winter of 1918 was especially cold. The recently ended war made it difficult to get the proper amount of coal to heat the orphanage, causing the pipes to burst when the temperature dipped too low. It was in January of that year when the temperature dropped to such a degree that the underground water supply froze, and when the pipes burst again a thick layer of ice formed on the floor. As the children moved across the floor in bare feet a few of them developed severe cases of frostbite. Not knowing any better, the frostbitten children held their feet up to kitchen stoves, damaging the tissue so badly that their feet had to be amputated. It was this incident that forced all of the children to be removed and moved to the New York Colored Orphan Asylum. Instead of completely shutting the organization down, the trustees of the institution decided to continue to use funds to support the education of Black children. Decades later, in 1956, the Howard Memorial Fund was created and is what remains of the legacy of the Howard Colored Orphanage and Industrial School.

Visit the Archives

- Howard Orphanage and Industrial School Photograph Collection, New York Public Library Digital Collection

- Howard Orphanage and Industrial School records

Resources

"Colored Orphan Home Gets a Pigmy". (1906, September 29). The New York Times, p. 7. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/proquest-historical-newspapers-new-york-times-1851-2006-w-index-1851-

Howard Orphanage and Industrial School Photograph Collection, New York Public Library Digital Collection

Howard Orphanage and Industrial School records, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

"Little Colored Orphans: Their Pleasant Brooklyn Asylum and How They Live". (1894, July 22). The New York Times, p. 16. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/collections/articles-databases/proquest-historical-newspapers-new-york-times-1851-2006-w-index-1851-

Mabee, C. (1974). "Charity in Travail: Two Orphan Asylums for Blacks. New York History", 55(1), 55–77. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23169563

"The Tuskegee Plan Will Be Given a Trial on Fertile Long Island Farm". (1911, March 19). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, p. 4. Retrieved from https://www.nypl.org/node/496043

Databases Used

More in the Black New York Series

- Catherine Latimer: The New York Public Library's First Black Librarian

- San Juan Hill and the Black Nurses of the Stillman Settlement

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

This article

Submitted by Shannon (not verified) on June 20, 2020 - 12:28pm

Howard Orphanage

Submitted by Lara Thompson (not verified) on June 24, 2020 - 6:04pm