Black Aesthetics in the Digital Collections: Thoughts on Black Portraiture

In part two of her Black Aesthetics blog series, our Communications Intern, Kiani Ned, examines the representation of the black body in portraiture:

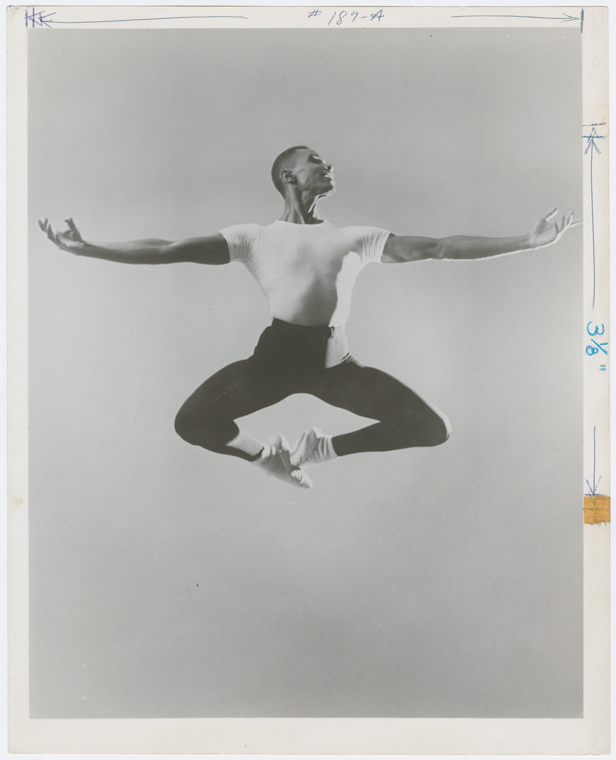

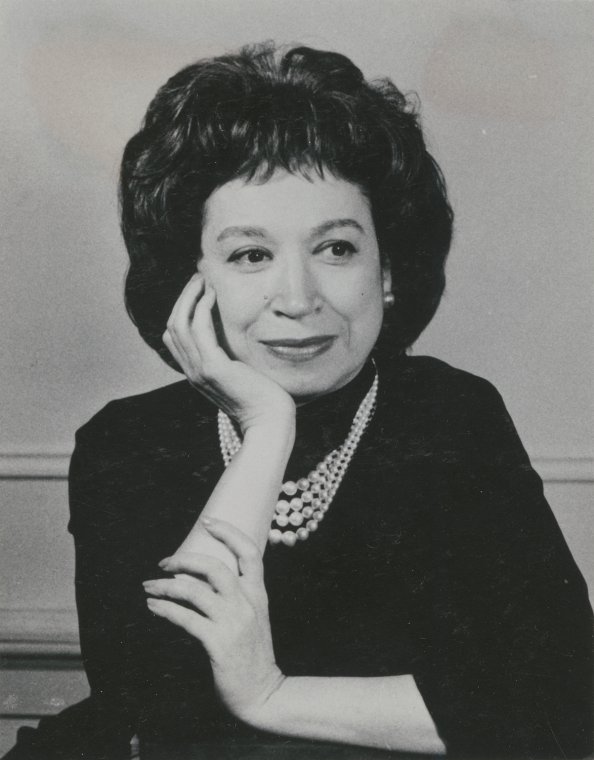

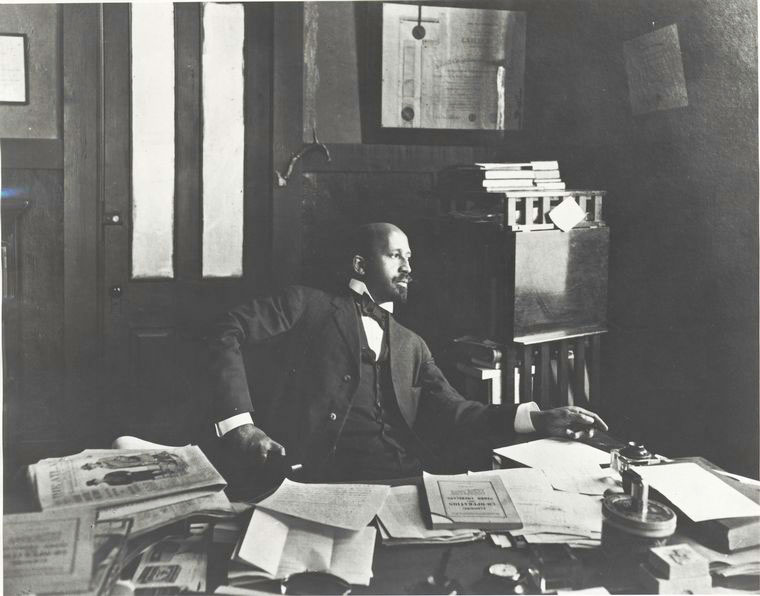

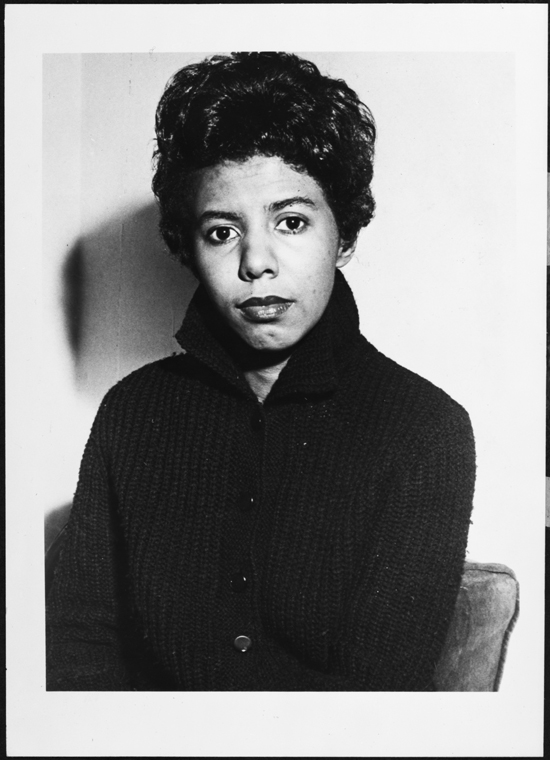

Portraiture is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the art of making portraits”—a portrait being detailed and graphic descriptions, usually of people. If art is a means by which a culture and peoples recognize and define themselves then images, or portraits, greatly influence the way that we perceive ourselves and each other. One could consider black portraiture to be a facet of black aesthetics, in that it centralizes the black image, illustrates a black existence, and thus implies a cultural position.

Over the last decade, the paintings of Kehinde Wiley have gained incredible fame because of his ornate and regal rendering of black men and women. Wiley alludes to Old Master paintings of the Western art tradition. As brown women and men assume the positions of kings and queens in the paintings, his work makes poignant and implied commentary on the black subject in art and society.

Understanding that the black body is inherently diasporic and nuanced, the questions of what it means-- what it looks like, what it sounds like, and what it feels like, to represent black folk in art and images are globally reconciled. The black subject in images is the primary subject of New York University’s Black Portraiture Conference—a series of panels and conversations that have been held around the world—previously New York City, in Florence, Italy in 2015 and this November in Johannesburg, South Africa.

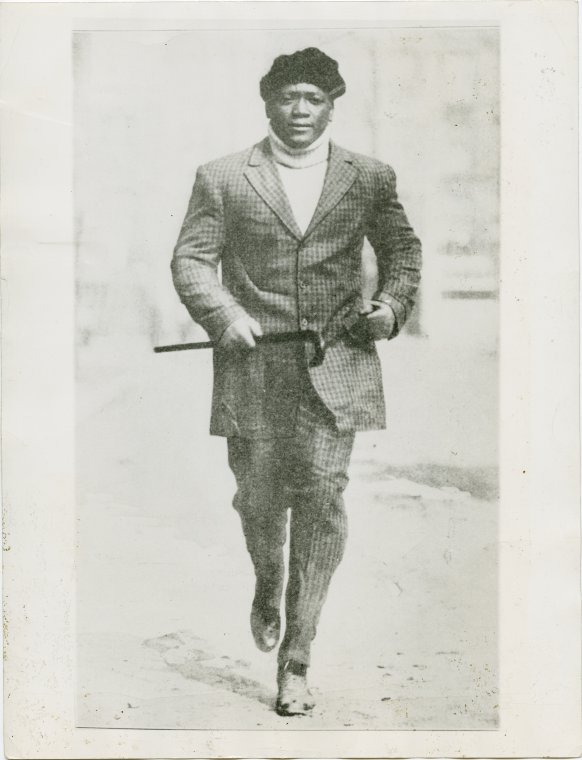

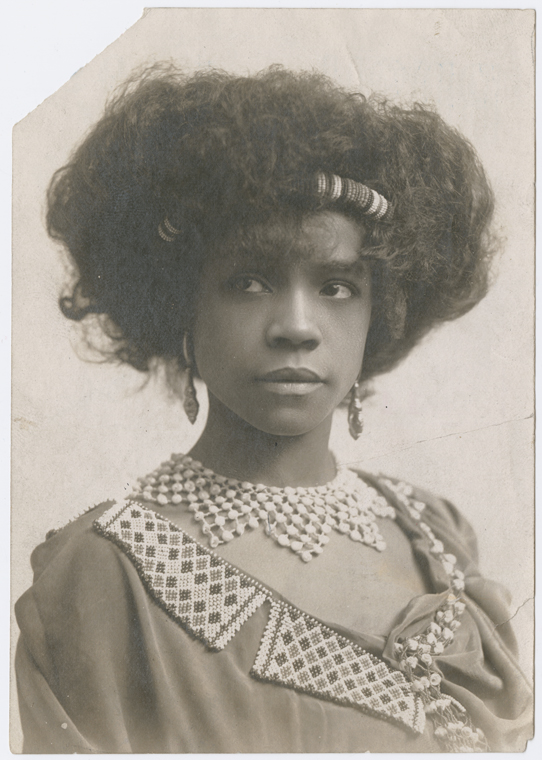

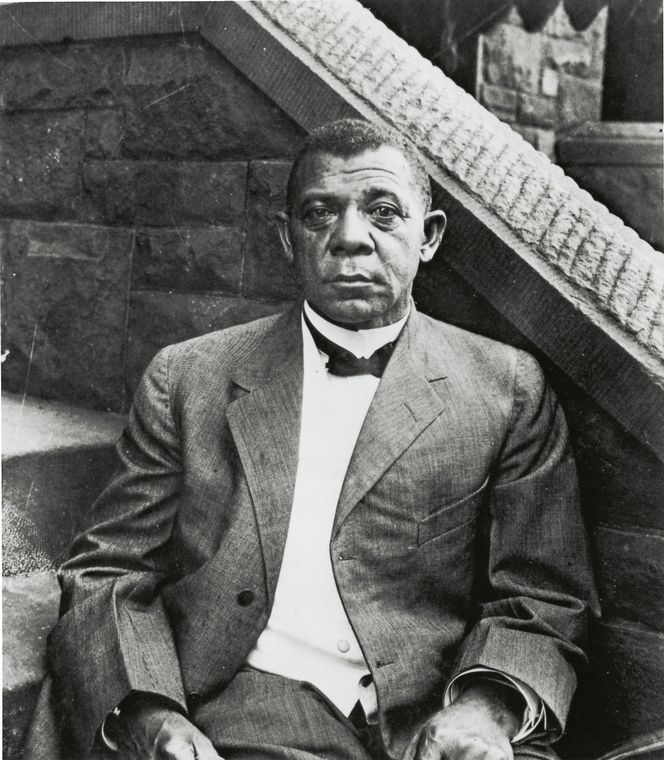

Much of the black narrative revolves around the carving of space for culture, identity, and existence where none exists. In the same way that we are likely to take a selfie to proclaim our “hereness” to the world, so, too, did black people since at least the early twentieth century in photographic portraits. The New York Public Library’s Digital Collections house a number of digitized photographs dating back to the late nineteenth century. A good amount of those photographs are of black people simply posing—using their image to carve some visual space, some identity, some culture for us to find later.

Discover more books on black imaging in our Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division:

- Black Portraiture In American Fiction; Stock Characters, Archetypes, And Individuals

- Cutting A Figure: Fashioning Black Portraiture / Richard J. Powell

- Imaging The Great Puerto Rican Family: Framing Nation, Race, And Gender During The American Century / Hilda Lloréns.

- Representing The Black Female Subject In Western Art / Charmaine A. Nelson

- Claiming B(l)ack Manhood, Claiming Souls: Male Portraiture In Novels By Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, And Gloria Naylor: A Womanist Reading / By Weihua Zhang

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Black Aesthetics in the Digital Collections

Submitted by Dawn Cunnane (not verified) on July 22, 2016 - 12:08pm

Wonderful blog post. Very

Submitted by Nancy (not verified) on August 6, 2016 - 4:06am

Seeing

Submitted by Katherine Ellington (not verified) on January 1, 2017 - 9:14am