The Arm That Clutched the Torch: The Statue of Liberty’s Campaign for a Pedestal

“They have not been able to procure a whole statue, but they have ornamented the city with a nice large piece of the intended statue’s arm” (New York Times, Feb. 26, 1877).

The Statue

Officially titled Liberty Enlightening the World, the Statue of Liberty was first envisioned as a lighthouse at the entrance to the Suez Canal before evolving into the Lady Liberty we know today: a symbol of American independence and Franco-American friendship.

Representing freedom, patriotism, and immigrants’ first sight of the New World, it is now difficult to imagine the New York Harbor without this iconic American symbol. However, sparking enthusiasm for this project wasn’t as easy as some might imagine.

A Pedestal Problem

Led by designer Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, France proposed to bestow the statue to the United States, while Americans were asked to fundraise for its pedestal. Lady Liberty did need a place to stand, after all. Because Americans were not particularly passionate about this fundraising endeavor, Bartholdi developed a plan to raise attention and money: The Arm of Liberty was going on a journey.

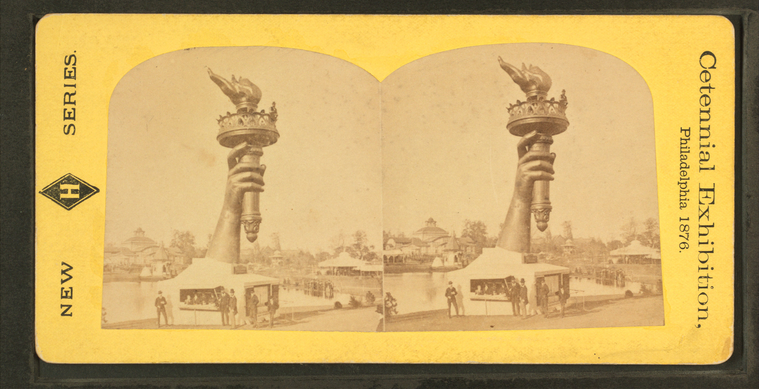

First presented at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition (though delayed until one month before its closing), thrill seeking visitors could buy tickets to climb a ladder in the statue’s arm up to the torch, fostering curiosity and excitement in Bartholdi's creation.

“Finally, our eyes were gladdened by the actual receipt of a section of “Liberty,” consisting of one arm; with its accompanying hand of such enormous proportion that the thumb nail afforded an easy seat for the largest fat woman now in existence” (New York Times, Sept. 29, 1876).

“An Isolated and Useless Arm”

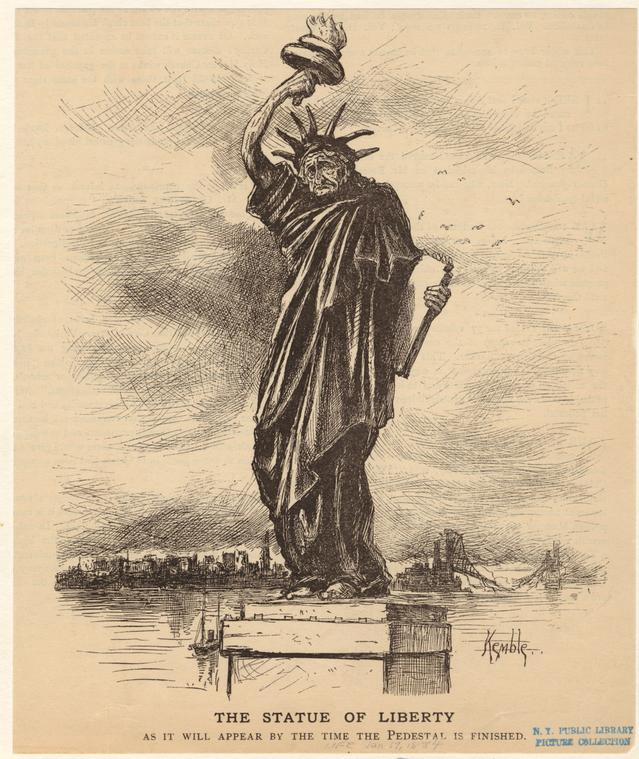

Despite sparking public interest, the Centennial Exhibition raised concerns about fate of the rest of Lady Liberty’s body and, in September 1876, the New York Times reported that “the statue has been suspended in consequence of a lack of funds.” Bartholdi chose the arm (over other body parts) because it would make an acceptable standalone structure if the project failed, and for some time, it seemed very possible that the arm is all we would have.

Igniting a Rivalry

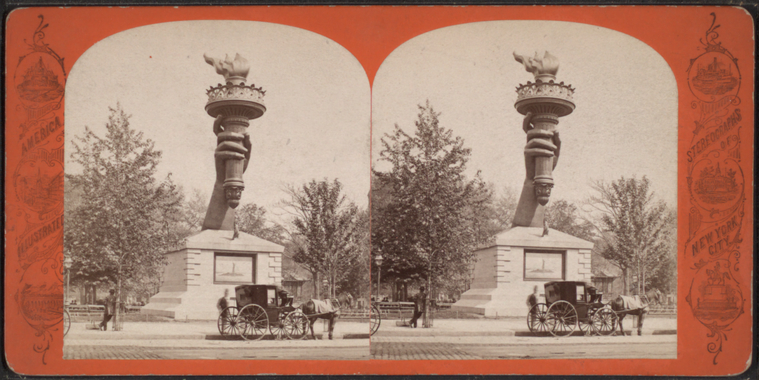

In a clever response to the New York Times, Bartholdi said that he might just allow Philadelphia to claim the statue instead of the intended New York Harbor. Within a few months, New York took Bartholdi’s bait and announced that the hand and torch would be displayed in Madison Square while they awaited the rest of the statue.

Six Years in Madison Square

With the wrist reaching treetops and rooftops, and the flame high enough to see for many blocks, the Arm of Liberty became a long-standing advertisement for the statue from 1876-1882. Souvenir photographs were sold, and for 50 cents, visitors could climb a ladder leading to the balcony (NYPL, 1986). While this massive arm triggered public enthusiasm for the project, it eventually began to blend into the city’s background, with its surrounding grounds “infested” with infants and children.

Critics, however, did not feed into this excitement, and mockingly suggested that the statue’s other body parts be scattered throughout the city. In fact, they quipped, “we have hardly a public statue which would not be improved by being [divided] and distributed” (New York Times, Feb. 26, 1877).

Lady Liberty Was Going Where?!

Rivalries continued over the years, and despite New York’s apparent indifference to the statue, they were appalled when another city tried to claim Lady Liberty. A monument so iconic to New York, it is difficult to imagine the Statue of Liberty anywhere else. While Philadelphia was always a contender for the statue, Boston had also jumped in on the competition. New Yorkers weren’t thrilled about this.

Even more shocking was the possibility that the Statue of Liberty could have rested atop the Washington Monument, 150 feet high at the time. “You would have been surprised to see how nicely the statue fitted the monument. It really seemed to have been made for it” (Washington Post, March 27, 1883).

After years of procrastination, New Yorkers did not want to lose the opportunity to host Liberty Enlightening the World, and were determined not to let another city “steal away our grand, symbolic, international, one hundred and twenty feet high statue” (New York Times, Oct. 3, 1882).

A Push for the Pedestal

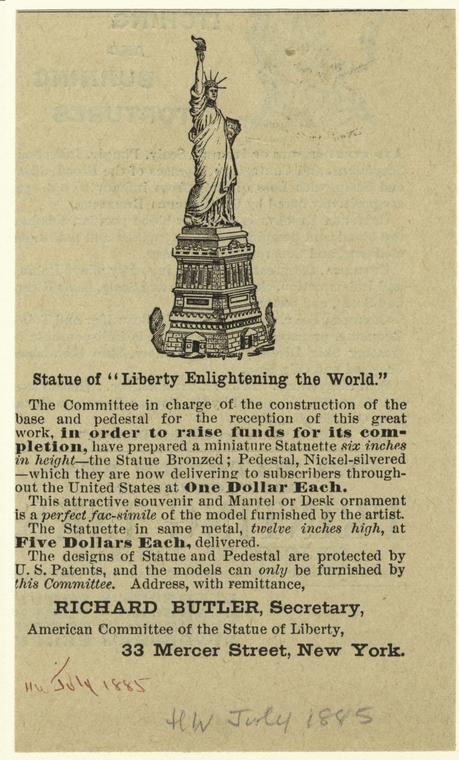

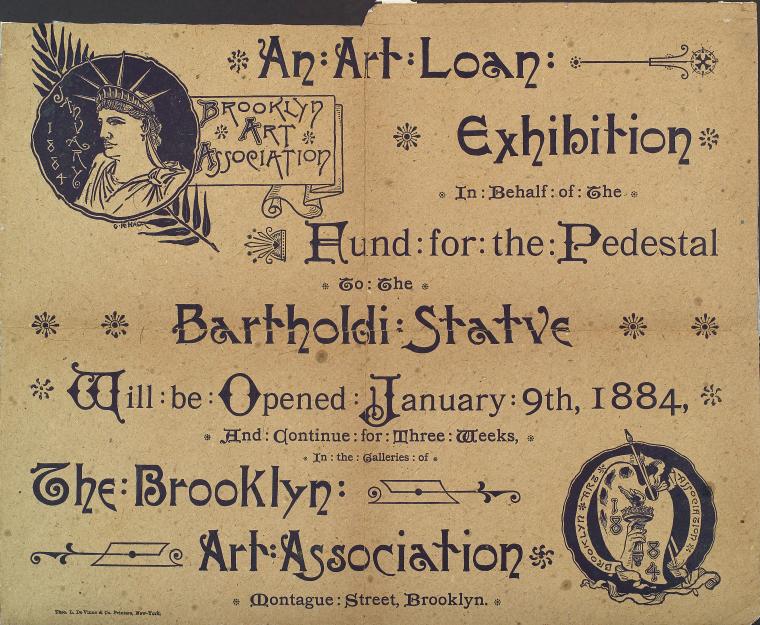

Eventually, donations for the pedestal were collected more aggressively. Fundraising efforts included benefit concerts, art exhibits, and auctions selling models of the statue, souvenir photos, sheet music, and other mementos. Campaigns by the American Committee and the World newspaper (headed by editor Joseph Pulitzer) were also instrumental in raising essential funds.

Among these auctions was an 1883 Art Loan Exhibition, where Emma Lazarus’ poem “The New Colossus” was donated, and later became the sonnet held by Lady Liberty herself 1903 (Berenson, 2012).

Ultimately, New York and the rest of the country resolved to raise sufficient funds and see the statue through to completion. “Our failure to provide a suitable pedestal is the only thing that stands in the way” (New York Times, Oct. 3, 1882).

The Statue of Liberty was finally dedicated on October 28, 1886 on Liberty Island and has reigned as an unforgettable symbol of hope and freedom.

Further Reading

- Statue of Liberty (New York, N.Y.) -- History.

- Statue of Liberty National Monument (New York, N.Y.) -- History.

- Bartholdi, Frédéric Auguste, 1834-1904.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

purchasing prints?

Submitted by Joyce Vaudreuil (not verified) on June 17, 2015 - 8:22pm

Purchasing Prints

Submitted by Megan Margino on June 19, 2015 - 10:58am

Angle of outstretched arm

Submitted by Marilyn Boatright (not verified) on July 23, 2018 - 12:48am