Play Strike! Exploring NYC Playgrounds Through Historical Newspapers

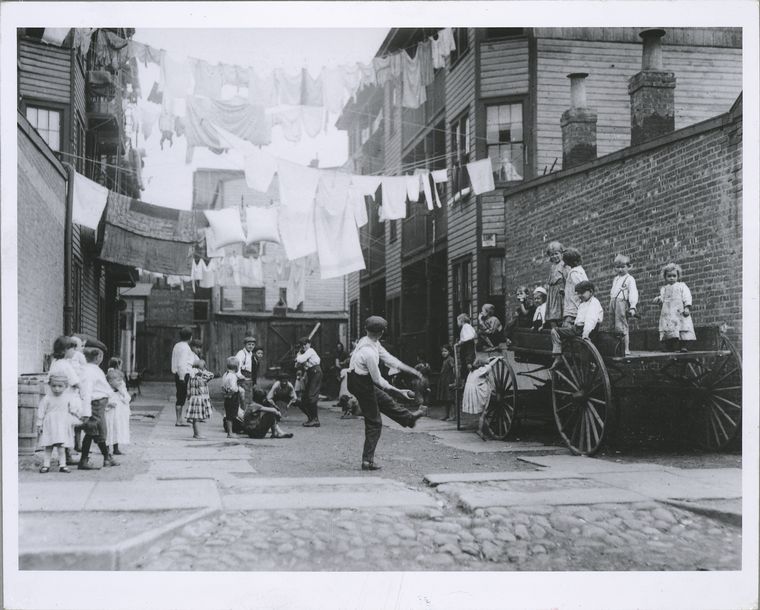

At the turn of the 20th century, children’s lifestyles were not quite what they are today. Child labor laws were not declared constitutional until 1938 and children largely socialized with their adult co-workers in dance halls, gambling dens, and gin mills. It was this children-as-adults culture that sparked the play movement, removing children from the “physical and moral dangers of the street” to playgrounds, under the direction of trained play leaders.

“City streets are unsatisfactory playgrounds for children, because of the danger, because most good games are against the law, because they are too hot in the summer, and because in crowded sections of the city they are too apt to be schools of crime” (A Study of an Urban Community and its Children).

Familiar names were heavily involved in this movement, including photographer and journalist Jacob Riis (named the first Honorary Vice President to the Playground Association), and legendary reformer Jane Addams, who spearheaded the campaign to provide safe spaces for socializing and sports.

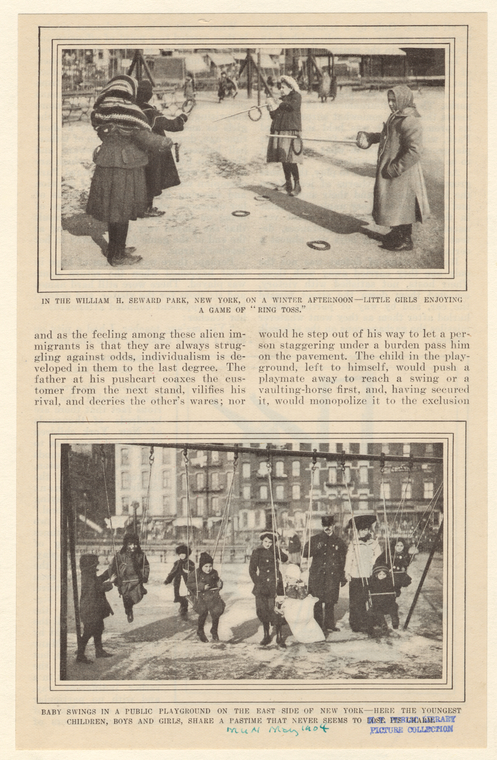

Evidenced through the New York Times, New York City’s demand for playgrounds began well ahead of the national campaign. First studied by the Tenement House Committee in 1884, organized movements for playgrounds began in 1889 and 1891 with the Brooklyn Society for Parks and Playgrounds and the New York Society for Parks and Playgrounds, respectively. NYC Parks & Recreation provides a comprehensive timeline of its history.

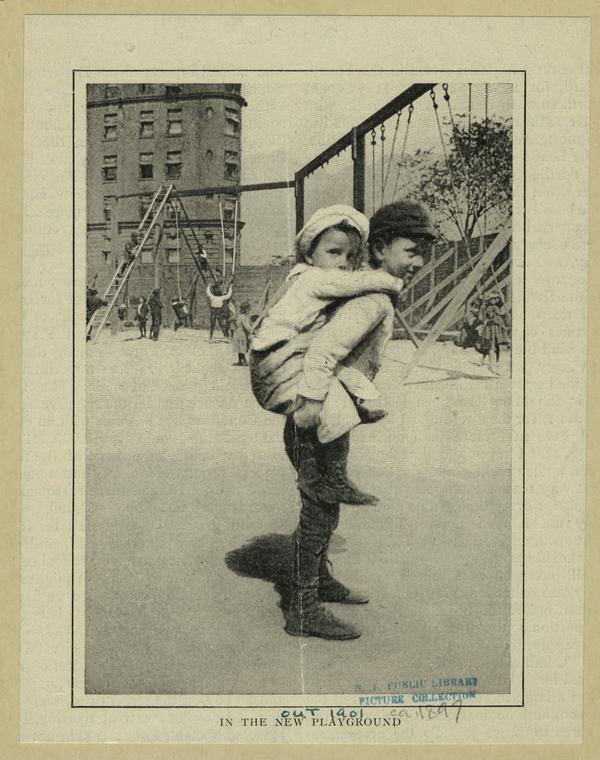

This call for city playgrounds is well documented and often commended in news coverage. Referred to as “pleasure resorts” and “vacation playgrounds” in numerous newspaper articles through the early 20th century, the existence of these parks became rooted in the notion of restoring children's social morality.

One 1890 New York Times article claims that city playgrounds will lessen the need for hospitals and charity asylums, as they would, in theory, provide children with a “chance to work out their own salvation, physically, as well as morally and mentally.”

A 1905 Washington Post feature on New York City playgrounds even credits these spaces to reclaiming children from evil influences, breaking up gang fights, and providing a road to “good American citizenship.” While these claims may seem a bit strong, it might be difficult to argue that it would be a good idea for children to work off their physical energy “properly and innocently” rather than among the misery and squalor of garbage cans and alleys, as suggested in another 1905 Washington Post article.

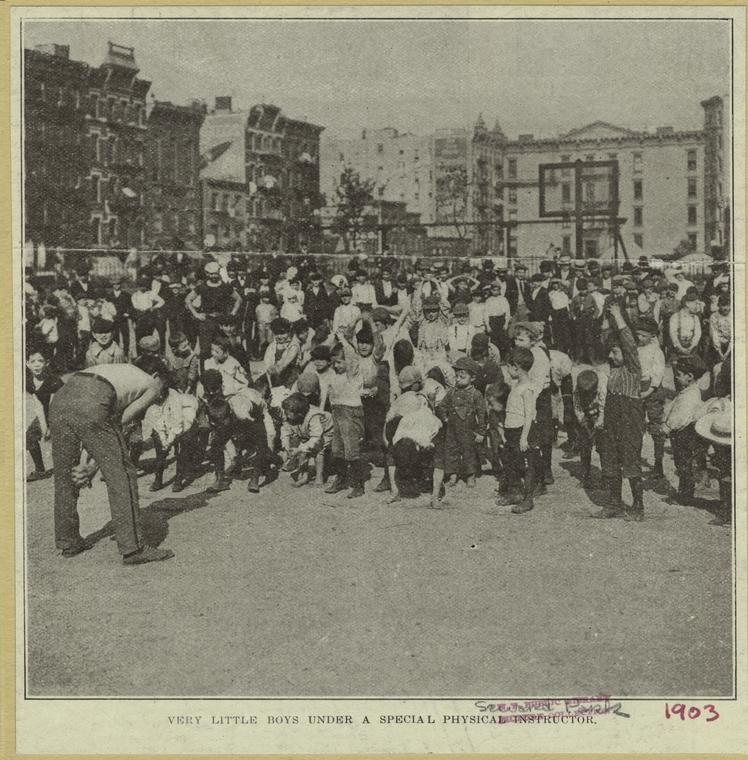

This movement also completely transformed how existing parks were used. The Washington Post’s 1905 “Playgrounds in New York City’s Parks” details the evolution of these spaces. Rather than displaying “keep off the grass” signs with ornate landscaping, parks now signified an outlet for sports and games. Intended for use by the people (and sometimes specifically designed for poor tenement children), not only were playground fixtures constructed, but balls, bats, dumbbells, tennis racquets, and even trained playground leaders were provided in parks throughout the city. Most popular sports included lawn tennis, baseball, track, croquet, cricket, lacrosse, volleyball, and football. Reaching beyond playing casual pickup games, each playground had organized competitive teams (junior clubs ages 7-14 and senior clubs ages 14-18). Playgrounds across the city competed against each other, culminating in a grand tournament each summer known as the Playground Games - growing to over 20,000 contenders in 1917.

A Playground Strike

While playgrounds were vital in removing children from dangerous streets and re-instilling their innocence, these children did not take their play lightly. While a 1905 Washington Post article comments,“watch a child’s face as he plays and you will note its seriousness,” a group of Bronx boys showed just how serious they were by organizing and effectively executing a strike—a playground strike.

Reported in August 1912 New York Times and New York Tribune coverage, a group of Bronx children sparked an uproar in their boycott of the Bronx House Playground for the firing of its playground leader. This playground strike was led by a bold 10 year old boy who organized dozens of children to picket the playground and threaten any intending play-goers.

While referred to as a joke by the president of the Park & Playgrounds Association, this operation stirred up enough attention for police reserves to be called in for crowd control. Though the police referred to the children as “orderly, but firm” in impeding anyone from entering the park, the strikers yielded pickets depicting skull and crossbones, with “terrifying pictures of boys with blackened eyes and missing teeth,” posing a warning to potential strikebreakers. Their tamest threats proclaimed "MR. BROWN OR PLAYGROUND CLOSED," referring to the play leader in question.

While some may have looked longingly at the empty playground, the protesters did not enter the grounds—following orders issued from the 10 year old leader's “street corner strike headquarters."

Ultimately, the strike only lasted several days, though it left a lasting impression with the local papers and the Parks & Playgrounds Association President, who seemed quite disappointed with the playground strikers. In a response to their public apology, this president replied, “the success of the Bronx playground must depend upon boys like yourselves who have the manliness to admit when they have made a mistake.”

And what were Mr. Brown’s charges? He led children on unauthorized expeditions throughout all parts of the city. This may explain why the children were so unwilling to accept his departure. The children did, however, partially succeed in having their play leader’s status placed under “serious reconsideration.”

Further information on the history of New York City playgrounds can be found through historical newspapers, accessible through the NYPL databases: Proquest Historical Newspapers, America's Historical Newspapers, and others.

Books and other relevant publications can be found through the NYPL Classic Catalog, under the subject headings: Parks -- New York (State) -- New York., Play -- New York (State) -- New York., Playgrounds., and Children -- New York (State) -- New York -- Social conditions.

For photographs of NYC playgrounds, the NYPL Digital Collections can be searched by the topics: Playgrounds -- New York (State) -- New York, Children playing outdoors -- New York (State) -- New York, Boys -- New York (State) -- New York, and Girls -- New York (State) -- New York.

The Museum of the City of New York Collections Portal also holds a wealth of playground photographs.

The New York City Department of Parks and Recreation also provides historical details of NYC playgrounds and parks, photographs included.

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

Comments

Playgrounds of NYC

Submitted by Lawrence Stelter (not verified) on September 5, 2014 - 9:48pm