Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.

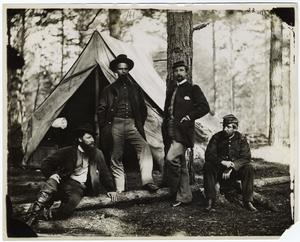

![[United States Soldiers With Rifles, 1850s.], Digital ID 831397, New York Public Library [United States Soldiers With Rifles, 1850s.], Digital ID 831397, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=831397&t=w)

![[Women And A Man Standing Outdoors, United States, 1842.], Digital ID 802198, New York Public Library [Women And A Man Standing Outdoors, United States, 1842.], Digital ID 802198, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=802198&t=w)