George Balanchine's Dancing Cat

Although The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has one of the largest collections of performing arts assets in the world, there aren't many children’s books in the archives. One book about cats does stand out, though–a book about one cat, in particular, named Mourka.

What is a cat book doing at the Library for the Performing Arts?

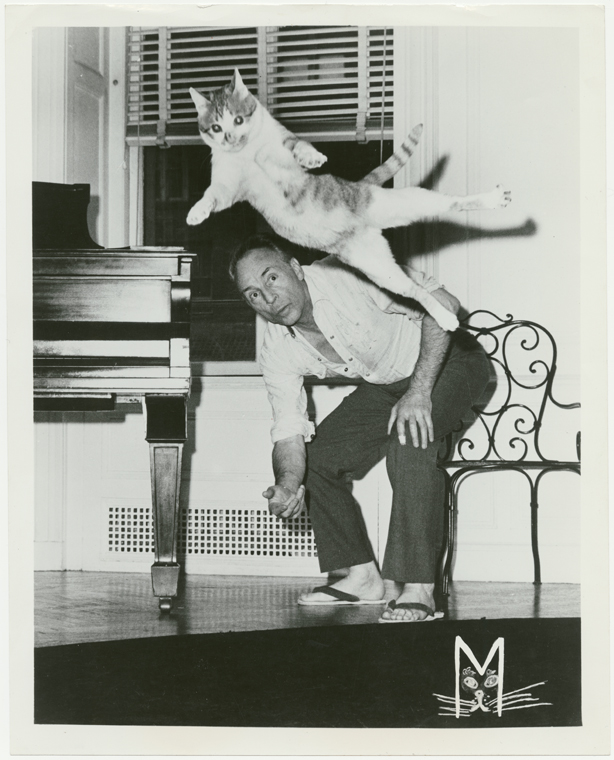

“The past two years,” the book begins, speaking from the perspective of Mourka the cat, “I have been living with Mr. Balanchine.” Mr. Balanchine, of course, is George Balanchine, one of the most influential ballet choreographers of the 20th century, and Mourka was his cat. “We posed together for a photograph that is now world famous,” Mourka goes on to explain.

The photograph was taken by none other than Martha Swope, a dancer turned photographer who over the course of her life captured over 800 productions of ballet, musicals, and theatre in New York. Balanchine’s performance with Mourka was one of them.

And apparently, it was a performance. According to his biography by Bernard Taper, Balanchine had actually trained Mourka how to dance jetés and tours en l’air. Indeed, Mourka, the book, is full of images of Balanchine’s cat’s ability to leap and glide through the air like a ballerina. Speaking of his cat, Taper writes that Balanchine “used to say that at last he had a body worth choreographing for.” Balanchine’s obsession with cats—and being photographed with them—seems to have gone back as early as 1949. A series of photographs taken by Frederick Melton in the Jerome Robbins Dance Division archive shows Balanchine posing with his cat in a birdcage—although notably not Mourka, but a different cat that appears to be Siamese.

Meanwhile, the "world-famous" photograph shows Balanchine in rapt attention as Mourka twists his body, possibly reaching for a ball that Balanchine tossed into the air. This photograph was featured in Life magazine and apparently caused such a sensation that a book deal was later penned with London publishers Sidgwick & Jackson. Martha Swope took more photos of Balanchine’s cat, as well as others, in human-like poses and situations. These were featured alongside a tongue-in-cheek narrative told from the perspective of Mourka, the cat, who could, according to the book cover, perform entre-chats and pas de chats—highly unlikely for anyone who knows a thing or two about ballet moves.

It’s not exactly clear who the book was intended for. While the pictures of the cats are fit for children, the narration of the book takes a playful tone more intended as inside jokes and puns more suitable for adults.

So, how did Balanchine, who Taper says had very little free time outside of producing ballets, get himself wrapped up in a book about cats? A little digging suggests there was something more to the story.

In fact, the narration was written by Balanchine’s wife at the time, a ballerina named Tanaquil LeClercq. The two met when she was on scholarship at the School of American Ballet, and years later, they got married. Taper writes that "LeClercq had become recognized by then as most nearly the ideal Balanchine dancer." He quotes a critic who asked about her performance in Balanchine’s La Valse, "What precocious sense of the transience of beauty and gaiety enabled her to dance this role with such infinite delicacy and penetration?"

LeClercq was one of the most promising ballerinas of the 20th century—Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, and Merce Cunningham all created roles for her. However, in 1956, at the age of 27, LeClerq contracted polio. The doctors barely saved her life, but could do nothing to save her career.

LeClercq was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of her life. When she returned home from the hospital in 1958, she was despondent. "For months she never mentioned ballet," writes Taper.

Balanchine "tried to be away from the apartment as little as possible," writes Taper. He did the shopping, cooking, and all the other household chores. But when he was gone, LeClercq "chose to remain alone in the apartment." Her only company was Mourka. It’s hard not to imagine that Mourka provided LeClercq with a sense of comfort in times of despair, as cats are known to do. Did LeClercq see herself in Mourka, the budding ballerina? A collaged photo of Mourka dancing with a ballerina from the New York City Ballet, pre-Photoshop, makes a compelling case. The book came out in 1965, nine years after LeClercq contracted polio.

Over time, LeClercq was able to discuss and think about ballet. She coached dancer Patricia McBride in the role LeClercq had originally created for La Valse. And in the 1970s, she started teaching at the Dance Theatre of Harlem. She was an inspiration to at least one dancer there, Stephanie Dabney, who became HIV positive in the early 80s, and also wondered what future career she would have as she had to walk with a cane. "Tanaquil was my favorite teacher," she told Wendy Perron for Dance Magazine in 2000, "She used her hands and arms as legs and feet."

One has to wonder how much Mourka played a part in rehabilitating LeClercq’s relationship with dance. And of course, Balanchine, too, was a part of it. At home, Mourka was his ballerina, and LeClercq was the audience. The performance was apparently legendary enough that his friend Igor Stravinsky requested an audience. Taper writes, in a later edition of his biography, “Guests present later said that was the only time they had ever seen Balanchine nervous before a performance.”

Read E-Books with SimplyE

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

With your library card, it's easier than ever to choose from more than 300,000 e-books on SimplyE, The New York Public Library's free e-reader app. Gain access to digital resources for all ages, including e-books, audiobooks, databases, and more.

If you don’t have an NYPL library card, New York State residents can apply for a digital card online or through SimplyE (available on the App Store or Google Play).

Need more help? Read our guide to using SimplyE.